M

|

|

|

Born:

Ireland c1862, died: 13th November 1937 (I.L.P.)

Dan

McCarthy was from Ireland and arrived in England from Australia and

joined NUBSO in 1892. He worked as a shoe laster and was employed at the

C.W.S. Wheatsheaf works. In 1895, he was elected to the Trades Council. He

was a member of the Board of Guardians for 18 years and was member of the

board of the Leicester Co-operative Society for 13 years resigning in

1919.

He was chairman of the Butchery

Committee of the Co-op. Board of Management and it was on his motion that

the dairy department was founded. He was responsible for starting the delivery of milk to Co-op

members. He was also one of the first people to press for a week's holiday

with pay for workers within the boot and shoe trade which was embodied in

the a jealously-guarded feature of the industry's national agreement - the

Holiday Provision Scheme of 1919. He was elected as a national organiser of NUBSO in 1919

and retired ten years later. He stood, unsuccessfully, in Westcotes ward

for the City Council in 1930.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle 7th

November 1929, Leicester Evening Mail 3rd November 1930, 14th Seprember

1934, 15th & 17th November 1937, Richards, T.F. & Poulton E.L.,

Fifty Years: Being The History Of The National

Union Of Boot And Shoe Operatives,

Leicester Co-operative Printing Society, 1924.

|

|

|

Born:

Scotland c1809,

died: Lewes 1886

The Rev A. F. MacDonald was a

graduate of Aberdeen who embraced Unitarianism in the early 1830s. He was

pastor at the Royston chapel from 1833-1848 and was also at Newhall Hill

Unitarian Church in Birmingham. He was described as combative personality.

In 1871 was a minister of the Free Christian Church on Narborough Road and

that year he chaired meetings of boot and shoe trade unionists in support

of

the nine hours movement. According to him:

The nine hours movement was required by the employed in

order that they might have more time for recreation and mental culture.

Some people thought that increased wages would be danger to the working

classes. But he had no more fear that too high wages would be a danger to the

working classes any more than he had a fear that too high profits would a

danger to another class. (Loud applause.)

In 1871, he was also active in

setting up a branch of the Workmen's Peace Association. He moved the

resolution which deemed the means employed for the settlement

of international disputes as costly, barbarous, and opposed to the best

interests of the people. It called for 'the establishment of high court of

nations as a remedy once practical and efficacious.' He was also active in

support of the opening of the Museum on Sundays.

He also gave two lectures in support

of women's suffrage in 1870 and 1871. In 1872, he became secretary of the

newly formed suffrage committee with his wife Ann MacDonald as one of the

committee members. By 1881 he had moved to Sussex.

Sources:

Leicester Journal,

8th, 15th December 1871, 16 February 1877,

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain and

Ireland: A Regional Survey, Alan Ruston, Unitarianism In

Hertfordshire

|

|

Born: 1870

died: 1911 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

Margaret MacDonald was educated

largely at home, although attending Doreck College for a short while. As a

young woman she was involved in various branches of voluntary social work,

including working as a visitor of the Charity Organisation Society in

Hoxton. By 1890 MacDonald had developed a keen interest in socialism,

influenced by the Christian Socialists and the Fabian Society. She joined

the Women's Industrial Council in 1894, serving on several committees and

organising an enquiry into home work in London which was published in

1897. She met Ramsay MacDonald through this work in 1895 and they married

in 1896.

Margaret MacDonald's political work

continued after marriage. She was particularly concerned about the need

for skilled work and training for women. She continued to work for the W.I.C

.

until 1910 and was also an active member of the National Union of Women

Workers. She was a supporter of women's suffrage though she was opposed to

militant action. She served on the executive of the National Union of

Women's Suffrage Societies. Margaret MacDonald was instrumental in

promoting a study in Leicester to investigate any correlation between

women going out to work and infant mortality. She invested her own money

and raised funds so the study could go ahead. Published after her death,

the study showed that there was no conclusive evidence to suggest that

women who went out to work neglected their maternal duties.

In 1906, she was involved in the

formation of the Women's Labour League, retaining an interest in its work

until her death from blood poisoning in 1911. The Baby Clinic was created

as a memorial to Margaret MacDonald and Mary Middleton, who both died in

1911. The goal of the clinic was to offer preventative healthcare to the

children of the poor.

Sources: Shirley Aucott,

Mothercraft and Maternity, 1997

|

|

Born: 1866,

died: 1937 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

MacDonald

can reasonably be considered one of the Labour Party’s three major

founding fathers. He began in the most disadvantaged of circumstances. He

was born in 1866, the illegitimate son of a poor Scottish girl in

Lossiemouth on the Moray coast. He made his way to London as an

impoverished science student and, significantly, made an early political

appearance as secretary of the Scottish Home Rule Association. But he also

became active in a variety of socialist organisations at that time, the

Social Democratic Federation, the Fabian Society, and eventually the

Independent Labour Party.

In 1899, he was successfully

nominated as candidate for the two member Leicester constituency by

T.F.

Richards. That year, he toured the country with Richards urging trade

union bodies to support the idea of supporting a working alliance between

the trade unions and the socialist societies such as the I.L.P. and the

Fabians. This alliance was to an extent drawn on the relationship of the

Leicester Trades Council, the Boot and Shoe Union and the I.L.P. in

Leicester. When he stood in the General Election in 1900, it was in the

midst of the Boer War. Whilst he polled no more votes that Burgess, it was

a good vote, given his public antipathy to the war.

In 1900, MacDonald became secretary

of the newly-formed Labour Representation Committee and his career as a

political figure of national stature, had begun. In the years before the

outbreak of the First World, MacDonald exercised a growing and visible

influence over the growth of the young Labour Party. However, unlike

Burgess, MacDonald was regarded sympathetically by the local

Liberal political establishment and it was the personal relationships with

men like Sir Edward Wood that provided the basis of the alliance with the

Liberals. This ‘Progressive Alliance’ between Labour and the Liberals,

brought considerable political and social changes in the Asquith-Lloyd

George era between 1905 and 1914. It was this alliance that ensured his

election in 1906 and in parliament he worked closely with the Liberals on

such issues as Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909, the National

Insurance Bill of 1911, and Irish Home Rule.

When he eventually became chairman of

the Labour party in 1911-14 he played a vital role in ensuring that Labour

kept up the alliance with the Liberals despite growing

antipathy to it in his own party. In 1913, he opposed the standing of a

second Labour candidate during the Leicester bye-election of that year and

it was clear that even in Leicester, where he enjoyed enormous prestige,

this continuation of this alliance was now unpopular.

George Banton was

unanimously selected as a candidate in the election, only to be told that

the party had to support the Liberal candidate. Banton dutifully stood

down. Members of the

British Socialist Party and Clarion supporters campaigned under banner of

‘Socialism not MacDonaldism.’

MacDonald was totally against

Britain's involvement in the First World War.

He called for peace through negotiation and maintained

links with his comrades in the German Social Democrats, some of whom were

also anti-war. His views were shared by the

majority of the I.L.P in Leicester and national figures such as James Keir

Hardie, Philip Snowden and George Lansbury. On 5th August, 1914, the

parliamentary Labour Party voted to support the government's request for

war credits of £100,000,000. MacDonald immediately resigned the

chairmanship. He wrote in his diary:

"I saw it was no use remaining as

the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result."

Five days later MacDonald had a

meeting with Philip Morrel, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel, Charles Trevelyan

and Arthur Ponsonby. They decided to form a committee to articulate their

opposition to the war. It became known as the Union of Democratic Control.

MacDonald and the U.D.C. argued that

main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like

Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the U.D.C.

should have three main objectives:

(1) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be

parliamentary control over foreign policy;

(2) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic

European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent

future conflicts;

(3) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate

the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might

provide a cause for future wars.

On 1st October 1914, The Times

published a leading article entitled Helping the Enemy, in which it wrote

that "no paid agent of Germany had served her better than MacDonald had

done. " Another article said that "Mr. MacDonald has sought to

besmirch the reputation of his country by openly charging with disgraceful

duplicity the Ministers who are its chosen representatives, and he has

helped the enemy State ... Such action oversteps the bounds of even the

most excessive toleration, and cannot be properly or safely disregarded by

the British Government or the British people."

In the midst of the pro war hysteria directed at

MacDonald and the Leicester I.L.P., their pre-war differences were

forgotten. Although, he was seen as a hero by his local

supporters, the press portrayed him as a pariah figure

and as a little less than a traitor. Ostracised and reviled,

he was expelled from many public bodies; he received white

feathers (a sign of cowardice) through the post and was physically

threatened. Although the first Russian Revolution led him to hope that

negotiations to end the war might start, the new Russian government

continued to fight. At home, public meetings became increasingly difficult

as small groups of 'patriots' draped in the flag tried to storm the

platform In 1918 he was

heavily defeated by J.F. Green a ‘patriotic’ ex-socialist and S.D.F.

member. Shortly after the election MacDonald commented:

The great fight is over. The

combination of hate, credulity, and reaction which we expected was

veritably effected, and the desirable villas of the West united with the

undesirable tenements the Centre to defeat Labour. The abandonment of

principle was wholehearted, and everything was forgotten in the one object

bringing about my defeat.

I had said things which disturbed the complacency of those people whose

conception of foreign politics is the same order a child's conception of

English history. I wrote sentences which were a stumbling-block to them.

They wanted to believe fairies, and whoever said fairies did not exist was

an enemy of society!

In the period 1918-22, MacDonald

emerged rapidly as Labour’s outstanding leader. His reputation as an

anti-war protester, was now a glowing asset as the domestic and foreign

policies of the Lloyd George coalition unravelled amidst unemployment and

international tension. MacDonald was ideally placed to appeal to

embittered trade unionists furious at the government’s betrayal of pledges

to build ‘a land fit for heroes’, to middle-class intellectuals disgusted

by the injustice and stupidities of the Versailles and other peace

treaties and the wider public to whom he seemed a ‘brave new world’

figure, full of hope for a better society.

In 1929, having won the General

election, MacDonald was awarded the freedom of the City, despite

opposition from local Tories. Two years later, MacDonald was prime

minister of an anti Labour ‘National’ government and was reviled as a

traitor by his former colleagues.

In July 1931, MacDonald backed a

proposal that the government should reduce its public spending with a massive

cut in unemployment benefits. The proposal was rejected by the cabinet,

MacDonald resigned and he was persuaded by the King to head a new

coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders

as well as Labour ministers. The 1931 election saw the loss of the two

Leicester labour MPs. However despite MacDonald’s huge following

Leicester, the formation of the National Government did not create any

splits or divisions in the local Labour Movement.

Sources:

The Formation Of The Labour Party

-Lessons For Today, Jim Mortimer, 2000, Bill

Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism, Birmingham Post,

30th July 1913, The Times, 1st Oct 1914, Liverpool Echo, 27th December 1918,

John Simkin, Spartacus.

|

| |

Born Newcastle? c1875, died Leicester, April 1939, (I.L.P.&

Labour Party)

Mary Mackintosh had held the post of

Foster Mother within a cottage children's home run by the Board of

Guardians at Countesthorpe. In 1904, she stood as a a Labour candidate for

the Guardians and criticised the Labour representation Committee for only

running two women candidates.

She resigned as Foster Mother at

Countesthorpe in 1917, but the Clerk of the Guardians, Herbert Mansfield,

refused to give her testimonial as to her character. Attempts by Labour

guardians to grant her a testimonial failed. She had her revenge when she

eventually elected to the Guardians in June 1919. She attempted to improve

the conditions for vagrants at the workhouse. The were required to go to

bed at 5pm and wanted males to have straw mattresses as well as the

females. She also wanted better heating arrangements, but this was

rejected by the Liberal-Tory majority. In 1921, she criticised the

guardians for paying different rates of relief to men and women, but her

proposal was voted down. At the time of the 1921 unemployment crisis, she

urged the unemployed to march to the Guardian's office in Pocklington's

Walk and demand relief.

You are entitled to it. Go in an orderly manner and demand what you were

promised last Friday.

When 21 year old Edith Roberts from

Hinckley was sentenced to death for the murder of her new born child in

1921, Mary Macintosh led the campaign for a reprieve and a petition

gathered 30,000 signatures. A reprieve was eventually granted and Edith

Roberts was released. Mary Mackintosh was described at the time as 'a

prominent figure in the local feminist movement.'

She was also a member of the Trades Council.

In 1930 she married William Grieves, a photographer.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer 20th

January 1904, 23rd September 1921, BOG minutes, June 1919, 25th October.

Leicester Daily Post 21st July 1920, Leicester Chronicle 6th August 1921, The Vote, 19th

August 1921, Leicester Mercury 6th April 1939

|

|

Born: 1855,

died: 1939 (Co-operator, Liberal Party, Labour)

Amos

Mann was born in Leicester on 16th January 1855, the son of William Mann,

who was a slater. He attended St Mary's and Laxton Street Church Schools, but

started work at nine years of age in a match factory where he earned 1s 6d

a week. Through night schools and his own

appetite for reading he broadened his education. Social, political and religious reform appealed to

him early in life and he took a keen interest in the campaign preceding

the passing of the 1870 Education Bill. He joined the Church of Christ,

where it was customary for members preach and teach without a minister. Being a gifted

speaker, he soon became a preacher where he was able to show a fluency and mastery of language. The Church of Christ, being

run by the laity, strengthened his belief in democracy and during his long

life, his idealism never left him. He was a lifelong abstainer and a

speaker on temperance platforms.

He was a member of Leicester No 1

branch of NUBSO, though by 1903 was a foreman. His first official

connection with the co-operative movement was as one of the founders of

the

Leicester Anchor Boot and Shoe Co-operative Productive Society, of

which he became the second president and held office for more than twenty

years. He was outstanding among the pioneers of the Anchor Tenants Ltd,

creators of the Humberstone Garden Suburb, being both a shareholder and a

committee member, and he lived there during the latter part of his life.

With other brethren he assisted in the formation of a Church of Christ at

the Garden Suburb which he regularly attended. He subsequently became

active in the co-operative, temperance, trade union and adult education

movements.

Amos Mann became a member of the

Leicester Co-operative Society general committee in 1898 but retired in

1900. Then in 1908 he was successful in being elected president of the

society and was re-elected annually to the presidency until he stepped

down in 1936. In 1922 he was elected to the central board of the

Co-operative Union from which he retired in 1936.

Mann was one of Britain's leading

advocates of producers' co-operation. For over thirty years he was

treasurer of the Co-operative Productive Federation, and was one of its

representatives on the joint exhibition committee of the Co-operative

Union and on the co-operative inquiry committee set up by the Co-operative

Congress in Dublin (1914). In 1911 he was elected president of the Labour

Co- partnership Association and in his last years he acted as organising

secretary of this association. Under the auspices of the Labour

Co-partnership Association, and later the Co-operative Co-partnership

Propaganda Committee, he lectured extensively, visiting most places of any

size in the country, and he also contributed many articles to co-operative

periodicals and published various books and pamphlets. One result of his lecture tours was a very much enjoyed

series of travel articles which he contributed to the Leicester

Co-operative Society Magazine. The Leicester Basket Makers (a co-op)

benefited from his special knowledge in the field of co-operative

production when he became their president.

He was elected to the Leicester Town

Council as a Liberal in 1897 for the West Humberstone Ward and, during his

period of office to 1908, he served on the Watch, Parks, Tramways and

Distress Committees. In 1914, he described himself as a radical who would

put the cause of Labour first and party second. He was opposed to the

First World War and represented and assisted conscientious objectors at

military tribunals. This led to him, in 1918, to be briefly adopted as a

Labour candidate for South Leicester Parliamentary constituency. He

withdrew in deference to the attitude of the co-operative society towards

his candidature. He believed that all progressive forces should unite, and

he was a strong opponent of class privilege. By the 1920s and 30s, his

views were a strong mixture of socialism, co-operation and

internationalism.

His other local interests included a

life governorship of the Leicester Royal Infirmary, membership of the

grand council of the Wycliffe Society for the Blind and treasurer of the

Leicester Free Christmas Dinner Fund. He was also a JP. It was said that

there was something prophetic in his being christened Amos, for he turned

out to resemble that ancient Hebrew Utopian reformer and idealist. He died

on 25 December 1939 at the age of eighty-four and the funeral service was

held at the Church of Christ, Humberstone, Leicester.

Sources: H. F. Bing, Dictionary of

Labour Biography, Leicester Co-operative Society, (1898)

Co-operation in Leicester, Amos Mann:

Co-operative Production from the Labour Co-partnership Standpoint

(1913), Democracy in Industry: the

story of twenty-one years' work of the

Leicester Productive Society (Leicester,

1914), Leicester Co-operative Society Magazine, January 1940

|

|

Born Leicestershire 23rd March

1791-13th January 1869 (Liberal)

John Manning was a grocer, a town councillor and

prominent member of James Mursell's

Harvey-lane Baptist congregation. At his china tea establishment at 16

High Street you could buy tea, freshly roasted coffee, Malaga raisins,

Seville oranges and all kinds of 'foreign fruit.' He had been baptised in

the Church of England and had been a churchwarden of St. Martin's

until he decided to become a Baptist.

From

the mid 1830s, there was a sustained campaign by non-conformists against

the compulsory payment of rates to the established Church.

When in

1841, William

Baines was sent to prison for his refusal to pay Church rates, there

was a huge outcry which result in Baines being elected to the Town Council

whilst in prison.

The churchwardens were undeterred by the support for Baines and persisted in summonsing those who refused to pay. (They had

even been rewarded by the gift of a silver cup and a purse of sovreigns).

John Manning, Albert Cockshaw and

several others were summonsed with the threat of distrait upon their

goods. John Manning said he would rather go to prison than give in and pay

the £1 he owed. He believed the rate to be illegal, but would refuse to

appear in the Ecclesastical Court, since he could not expect justice

there. Susanna Watts, a churchwoman, felt that the Church would lose more

than it would gain by martyring Non Conformists and paid his fine.

However, summonses and distraints continued to be issued from St Martin's

parish until 1849 when the Liberals secured a majority in the Vestry

ending the levy of Church rates in Leicester.

In 1842, he became the first chairman of the Complete

Suffrage Association. which was something of a haven for middle-class

reformers who shrank from the militancy of Thomas Cooper's brand of Chartism. Under the leadership

of Joseph Sturge, they made very similar demands.

In 1848, Manning took the chair at the joint meeting

between the Chartists and radicals which helped create a new alliance in

the town. In 1852, he proposed the radical

Sir Joshua Walmsley in very

glowing terms at the hustings during the parliamentary election of that

year . (He was Mayor of Leicester at the time). In 1856, he supported the

nomination of John Biggs as one of

Leicester's two MPs after the death of Richard Gardiner.

However his support for the radicals soon came to an end

when Sir Joshua Walsley proposed opening of the British Museum on Sundays.

This led to the desertion of many Baptists and Sabbatarians from the

radical camp and in 1857, he helped, with other Baptists to defeat

Walmsley and ensure the victory of the Whig John Harris. The defeat of

such a popular M.P. caused outcry in the town among those not entitled to

vote.

In 1859, the Leicester Mercury had still not forgiven

him. That year, Manning had claimed that he had never liked Sir Joshua

from the first to the last. The Mercury replied by reprinting his

speech in Walmsley's praise. It felt that "if eloquence

consists of coarse vituperation, then it must follow that Mr Manning is an

orator in the highest and most expressive sense of the term." It

also noted that in the past he had "laboured conspicuously, honourably

and disinterestedly in the very van of the reforming ranks."

He is buried in Welford Road Cemetery.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, 6th

March, 17th April 1841, 12th March 1842, 28th May 1859, Leicester Journal,

23 April 1841Leicester Chronicle, 3 April 1841,

7 June 1856, A. Temple Patterson,

Radical Leicester,

Leicester 1954.

|

John Markham's grave in Welford Road

Cemetery |

Born: c1802,

Wilbarston, Northants, died: 27th October 1861 (Chartist leader and

Liberal)

John Markham was said to have lived

and died within a few yards of Belgrave Gate. (in 1851 he lived at no 28,

now the site of the pawnbrokers, Cash Generator) His

schooling was limited and he was self educated, beginning life as a shoe

maker. He was a gifted public speaker and became a Primitive Methodist

preacher, first at George Street where his rebellious nature led to his

departure and then at Denman Street, where his colleagues took umbrage at

his political aspirations. This led him to retire to the ‘private ranks’

of the church.

In February 1838, John Markham urged

the working men of Leicester to cease supporting middle or upper class

politicians who were not prepared to secure the people their rights. He

urged them to form a political association of their own and this led to

the formation of a local anti-Poor Law Society of which he became

secretary.

In October 1838, the anti-poor law

agitation, the activities of the Leicester Working Men’s Association and

the efforts of the hosiery workers to stop the fall in wages was fused

together into the Leicester Chartists under Markham’s leadership. His name

appears at every phase of the Chartist agitation. He was shrewd and

level-headed and probably the most statesmanlike of the Leicester

Chartists. At the hustings, he was a formidable interrogator, especially

if the candidate was suspected of not being well up in respect of the

‘bill of rights.’ He had no time for insurrectionists and only once did he

use physical force language when he exhorted the Chartists never to think

of violence “until non-resistance would be a crime.” He helped

defeat the Whig candidate in the Nottingham election of 1841 and return an

anti poor law candidate, he also used his influence against the Whigs in

Leicester.

Markham did not share Cooper’s

hostility to the repeal of the Corn Laws. He believed the repeal to be

desirable, but the repeal in itself would not be a panacea to the ills of the

working class. Nevertheless, Markham found himself steadily being eclipsed

by Thomas Cooper.

Markham resented Thomas Cooperís

assumption of dictatorial power, his impatience with criticism, his

disdainful treatment of the Chartist committee and the violent tone of his

rhetoric. Markham was also disturbed by the unquestioning support that

Cooper gave Fergus OíConnor.

He had no truck with physical force Chartism. In his

view the advocates of physical were the worst enemies of the people,

because: "the nonsense which some had talked about physical

force had only the effect of driving sincere reformers from their ranks."

Early in 1842 there was an open and

furious quarrel between Markham and Cooper and the Leicester Chartists

split into two unequal parties: Markhamís smaller All Saints Chartist

Association and Cooperís Shakespearean Association of Leicester Chartists.

In 1843, Markham set himself up as an auctioneer and furniture broker and

the All Saints Chartist Association faded.

Like other Chartists, he played no

part in the 1848 Bastille Riots against the Poor Law, though he protested

over the brutal violence used against unoffending citizens. By this time,

with the departure of Cooper and Bairstow,

the divisions amongst the local Chartists had heaked and he was once

again in the

forefront of the movement. With the decline

of the Chartist movement, Markham reached an accommodation with those

middle class radicals who wanted an extension of the franchise. Markham

became a supporter of John Biggs and was elected to the town council for

the North Saint Margaret’s ward in November 1852 and was re-elected in

1855 and 1858 unopposed. During the election of 1852, the Leicester

Chronicle described Markham as a ‘Chartist’ candidate. As a town

councillor, he apparently took every opportunity to raise the claim of the

working classes to the franchise as a natural right. In 1852, he was also

elected as a Poor Law guardian and although opposed to the law, he tried

to ameliorate its harsher provisions, especially at times of depression.

He supported the Sunday League’s

proposals to provide rational recreation of Sunday as a counter attraction

to drinking, but in 1855 opposed attempts to close pubs on Sunday as he

believed it would interfere with individual liberty. He also supported the

Sunday opening of museums. He retired from business, due to heart disease and died aged

59. He was buried in Welford Road cemetery close to the grave of the veteran

radical and political associate George Bown.

Sources: Leicestershire Mercury, 17th

June 1848, Midlands Free Press 2nd Nov

1861 (obit), Leicester Chronicle 1852, 24th February 1855, J.F.C. Harrison, Chartism

in Leicester,

published in Chartist Studies Asa Briggs (ed) 1959

|

| |

Died: 1982

(Labour Party)

Arthur Marriott was an engine driver.

He was president of the Trades Council in 1952 and was delegate from the

Amalgamated Society of Locomotive Engineers And Firemen. He was elected to

the City Council in 1953, but lost his seat in 1959. He was re-elected to

the Council in 1964.

|

|

Died:

November 1985 aged 76 (Labour Party)

Lily Marriott joined the Labour Party

in 1937 and was renowned for her work in public welfare. She represented

Abbey ward for over thirty years, finally stepping down in 1983. From its

inception in 1946, she served on the Rent Tribunal and was chairman of the

Hillcrest Hospital Committee, the Social Services Committee and was a

member of the Public Assistance committee.

In 1959, she was elected to City

Council for the first time. She became Lord Mayor of Leicester in 1975 and

was awarded the M.B.E. and made a JP. She is commemorated by. Lily

Marriott Gardens, Rowlatts Hill, opened in 1988 and Lily Marriott House in

Aylestone.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, 27th

November 1985, Leicester City Council, Roll of Lord Mayors 1928-2000

|

|

Born: 13th

March 1941; died: May 27th 2004 (Labour Party)

The

son of a labourer, Jim Marshall was born in Attercliffe, Sheffield. After

elementary school and Sheffield grammar school, he took a BSc and a PhD at

Leeds University, which qualified him to become a research scientist with

the Wool Industries Research Association in Leeds (1963-68). He lectured

at Leicester Polytechnic (1968-74) and worked as a supply teacher and

market trader (1983-87).

His political career began in 1965 on

Leeds council and in 1970 he was the parliamentary candidate for

Harborough constituency and was subsequently elected to the City Council

for Aylestone and later Castle ward. In August 1972, Jim was one of nine

Labour councillors who rebelled over issue of Ugandan refugees. They took

issue with the ‘no room at the inn’ being approach taken by the leadership

of the Labour group. The following year Jim became leader of the group and

at the first meeting of the ‘new’ district council in June 1973 he

declared that it would have an important role in countering the effects

of racialism introduced into the City by the National Front’s election

campaign.

He first contested Leicester South in

February 1974 and won it the following October. In 1977, at the tail-end

of James Callaghan's premiership, he became an assistant whip. Later he

became

assistant home affairs spokesman (1982-83) before his Northern Ireland

appointment. In 1983, the Tories won Leicester South by 13 votes and Jim

worked as a supply teacher and a market trader.

On his return to parliament in 1987,

he became deputy shadow spokesman on Northern Ireland (1987-92), when,

with his boss Kevin Macnamara, he developed Labour's scheme for a

devolved, self-governing Northern Ireland. They even proposed that the

troubled province be jointly governed by Britain and Eire.

Jim’s frontbench hopes ended after he

voted for Bryan Gould, rather than John Smith, in the 1992 Labour

leadership contest, and, in 1994, he preferred Margaret Beckett to Tony

Blair. As a northern working-class, leftwing Euro-sceptic, he was out of

sympathy with the Blair project, denouncing the incoming prime minister's

cheerleaders in 1997 as a ‘bloody shower’.

He devoted himself increasingly to

Leicester, where an growing amount of his casework was bound up with

problems of immigration and visas. He was furious at the Tories for ending

appeals on denied visa applications in 1993, he was angered by the

slowness with which the Labour government restored the appeal system and

then hobbled them with charges. He and others dissuaded the Home Office

from demanding a £5,000 bond to prevent overstaying by Asian visitors.

Jim's parliamentary voting record

showed the extent of his unhappiness with his own side. In December 1997,

he voted against cuts in single-parent benefits; in 1998, he opposed the

abolition of student maintenance grants; in 1999, he voted to block cuts

in disability benefits, in 2000, he voted against government limitations

on the Freedom of Information Bill; in 2001, he backed a register of the

royal family's outside interests. He was among the first to oppose the

Iraq war. In June 2003, he defied a three-line whip on the university

top-up fees vote. He died in his office, aged 63, of a heart attack.

Sources:

The Guardian (obit), author’s personal knowledge

|

|

Born:

Leicester 17th May 1909, died: March 1987 aged 77 (Labour

Party)

Ted

Marston went the Brunswick and Curzon Street

Schools. In 1923, aged 14, he started work in the Carriage and Wagon

Department of the London and North Eastern Railway Company. 18 months

later became an apprentice bricklayer with a local building firm and

was for many years a building general foreman

with the Leicestershire Area Health Authority.

He joined the I.L.P. in 1928 was a

member of AUBTW (later UCATT) from 1928, becoming was its secretary from

1939. He was an Executive member of the Trades Council and was first

elected to the City Council in 1945 for De Montfort ward. He lost this

seat in 1949, but was re-elected in Abbey Ward in 1953. He was Vice Chair

of City Leicester Party (1958) and was leader of the Labour Group from

1966 to 1973. He was Lord Mayor in 1969 and an Alderman until 1973, when

the title was dropped.

In 1972, when the Amin government

started the expulsion of Asians from Uganda, Labour had just regained

control of the council and Ted Marston was leader. He was faced with

numerous petitions circulating against imminent arrival of refugees and

pressure from the Leicester Mercury which published racist letters

purporting to show how ‘the people’ of Leicester viewed the coming of the

Ugandan Asians. Faced with this situation, the Labour leadership gave way

and sent a deputation to Whitehall to tell the government that Leicester

was full up.

“We urged that the Minister should use his influence to

direct these people to other towns and cities where they would have more

opportunities than in Leicester.”

On 15 September 1972 (and for three

subsequent weeks) the Council placed a half page advert in the Ugandan

Argus declaring that there was no more room for Asians in the City,

urging the refugees not to come to Leicester. There was a revolt against

this descent into xenophobia by nine Labour councillors led by Cllr Rev

Billings whose dissent saved the Labour Party from complete ignominy. The

following year Ted Marston lost his leadership of the Labour group to

Jim

Marshall, one of the rebels and in 1976, he lost his seat. He was

commemorated by Marston House, St Matthews Estate which has now been

demolished.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, 31st

August 1972, and 16th March 1987, Valerie Marett, Immigrants Settling

in the City, 1987

|

|

Born: Apeton,

Staffordshire, 1865, died Leicester 1956 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

Amos

Martin went to Church Eaton, Grammar School and started work at the age of

12 as a grocer’s errand boy. He was then apprenticed as a clicker in the

shoe trade and had the usual experience of seasonal unemployment. In 1891,

he joined NUBSO and was soon elected to various positions within the

union, including national auditor. He was employed at the C.W.S. boot

factory.

Amos Martin was noted for his special

work in the area of figures. He was described as shrewd, calculating and

level headed. Apparently he did not give the impression as one who had

passionate feelings. However, he fought tenaciously and fiercely for the

interests of the poor at the meeting of the Guardians. He was respected by

his opponents, though there were some who hated him because of his “down

right manner of speech and brutal bluntness of manner.”

He was elected to Board of Guardians

in 1907 and served for 17 years. He became leader of the Labour

Guardians and was Vice Chair of the Board in 1916. At various times he was

President & Vice Chair of the Leicester Labour Party. In 1946,

although he wanted to retire, he was still serving as one of the Council's

elective auditors.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 24th

February 1924, Leicester Evening Mail 21st January 1946, 21st November

1956. Election address 1923

|

| |

Born:

Hinckley c1823, died: 1880

Mrs Mason was a seamer and became

secretary of the Seamers' and Stitchers' Society when

George Newell relinquished the post.

In 1877, she was living at 38 Denman Street in the Wharf Street area.

In 1875, she told a union meeting a the

Temperance Hall that at current prices she would have to sit from seven

o'clock in the morning until eleven at night, for five days, to earn four

shillings and six pence.

The union was founded in 1874/5 with

the help of George Newell, the Leicester Hosiery Unions and the Womenís

Trade Union League. Mrs Mason recruited women from Leicester and the

surrounding villages and within a few months there were 2,500 members of

the Union, chiefly adult women. They were paid so much per dozen. She told

an inquiry into the working of the Factory and Workshops' Acts that some

of the women employed their own children at home.

By 1875 the union had established an

out of work benefit scheme. Organising women outworkers was a sizeable

achievement and Mrs Mason must have been someone of remarkable

determination and perseverance. According to Mrs Fay, another union

member, it meant she had to go from place to place in all weathers to hold

meetings, walking miles on dark lonely roads.

The Seamers' Union had some success when the took their

grievances over poor pay to the Board of Arbitration. For the first time

an agreed set of prices was adopted and the union's members were urged not

to anything below the list price for their work.

She became the first woman delegate

to the Trades Council in 1875 and, in 1877, the first woman to address the

TUC. She told the Congress that a great deal of the work was done by

middle aged married women in their own homes. Sometimes the work was done

as a pastime; but widows had to earn their living by it and had to work

many hours. Some, women who did not have to cook dinner could earn 7s. or

8s. per week, but those with domestic duties might only earn, four ot five

shillings a week.... She knew a woman with a family of eight children, all

under 17 years of age, and only two of whom could go to work; yet the

woman was compelled to work because her husband was too idle to maintain

her and the family. (Hear, hear.) She wished there were laws passed to

make idle husbands maintain their families - (loud applause)

However the rise of factory

production and a decline in trade sent the fortunes of the union into

decline and with her early death from emphysema and bronchitis, the

Unionís organisational power was greatly diminished. The union lost 2,000

members, became insolvent and, by 1882, had merged with the menís hosiery

union.

Sources: Leicester Journal 12th

February 1875, Leicester Chronicle, 13th February, 8th May, 26th June

1875, 22nd September 1877, Midlands Free Press 13th

March 1875, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism,

Richard Gurnham, The Hosiery Unions 1776-1976, Shirley Aucott,

Women of Courage, Vision and Talent

|

| |

Born:

Middlesbrough, c1875 (Certified Teachers' Association)

Will Maw came to Leicester in 1902

from Lincolnshire. He became a delegate to the Trades Council from

National Federation of Class Teachers in 1909 (later Certificated

Teachers' Association.) During First World War, he served with the

Leicestershire Regiment. He became president of the Trades Council 1930

and was its General Secretary from 1932-45.

|

|

Born: 1827 died: February

19th 1888 (Leicester Democratic Association & Liberal)

Dan Merrick was a stockinger and was

the able leader of the Sock and Top Union of framework knitters formed in

1858. The union had 800 members at its peak in 1870. Merrick was a tall,

thin man and described being “as aesthetic as a cardinal…. poor of

purse, feeble of body, but strong in mind and great in his love of

humanity.” His thinking and sincerity and the firm way he gave

expression to his views made him a great power in his day, despite having

a thin and rather squeaky voice. He became the grand old man of trade

unionism in Leicester.

As a young man, Merrick was a

Chartist supporter, regularly attending Chartist meetings and taking part

in processions. His book: The Warp of Life (1876) contains eye

witness accounts of Chartism and Chartist demonstrations in the 1840s. He

was also a member of a short-lived co-operative society started by

Thomas

Cook which sold potatoes and flour from a stall in Humberstone Gate in the

late 1850s. He was a member of the first Co-operative Hosiery

manufacturing Society formed in 1869 and on the breaking up of that

society, he took part in the movement for carrying on the business under

the auspices of the Hosiery Union. He became a member of the board of

management of the second manufacturing society and held that position

until his death. Although a member of the Leicester Co-operative Society,

he did not join its board until 1878, becoming its secretary and then its

president in 1885.

Framework knitters had been opposed

to the practice of middlemen renting out knitting frames to stockingers

since the 1840s and before. Merrick gave evidence on the subject to the

Commission into the Truck System in 1871 and, along with Robert Bindley,

was subsequently successful in the campaign for legislation to abolish

frame rents and charges.

In January 1871, he was elected, as

part of the Liberal slate, as a working man candidate to the School Board.

He was re-elected many times and served on the board until his death. His

first election was supported by the newly formed Democratic Association.

The political aims and objects were to organize the newly enfranchised

working-class voter to support the call for universal suffrage. The

Association was in reality the organised working-class section of Radical

Liberalism. The Democratic Association also pressed for the speedy

establishment of Board Schools and against the use of rates to pay the

fees of denominational schools. When the Democratic association, became

the Republican Association he spoke on its platform.

In the after-math of the Franco

Prussian war, he helped found the Workingman’s Peace Association, which

called for international arbitration to settle disputes.

Merrick became the first working man

to be elected to the Town Council. At the time there was a property

qualification for councillors, all of whom had to declare they were worth

£1,000. Merrick had little money, but a sum of £1,000 was paid into his

account by his admirers. He looked forward to the time that working people

could succeed in sending a representative of their own class to the House

of Commons. He lost his council seat in the elections of 1876.

Merrick was deeply religious, a Congregationalist, and a member of the

Oxford Street Chapel. He was a Sabbatarian and in the 1870s was a leading

opponent of opening of the Museum and Free Public Library on Sundays,

despite the benefits it would bring to those who worked on the other days.

In 1871, Merrick had chaired the

first meeting to publicise the Nine Hour Movement which was inspired by a

strike of Newcastle engineers. The demand for a 54 hour week was taken up

by the local trade unions and the press published lists of local employers

who had agreed nine hour days.

In 1872, he

became the first president of the Leicester and District Trades Council

and remained president until 1885. Initially the Trades Council

represented just eight societies and was formed in the midst of the

controversy over the 1871 Criminal Law Amendment Act which made picketing

a criminal offence. Following a campaign, a new law, the Conspiracy and

Property Act (1875) permitted peaceful picketing.

In 1875, Merrick told an inquiry into the working of the

Factory and Workshops' Acts that he was a working as a frame-work-knitter

in a factory. They commenced work at six o'clock and worked until

half-past five o'clock, with half an hour for breakfast. They worked ten

hours a day.

During the 1870s and

1880s, the Trades Council entered into the mainstream of working-class

politics, endorsing candidates to the Town Council and School Board with

close ties to the Liberal Association. Both Merrick and

George Sedgewick

nominated the Liberal parliamentary candidate McArthur in 1886. In 1877, Merrick became president of

the Trade Union Congress for its meeting in Leicester and was nominated

for the office of JP in 1886 by the Trades Council.

Sources:

Leicester Journal, 22nd

September 1871, Leicester Chronicle, 26th 26

June 1875, Midlands Free Press 25th

February 1888, Leicester Daily Post 21st February 1888,

Leicester Co-operative Society, (1898) Co-operation in

Leicester, Bill

Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

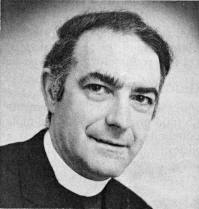

Died:

November 2005 aged 82 (Labour Party)

Ken

Middleton was dominant figure within local government during the 1970s and

early 1980s. He was educated at a grammar school in Southampton and went

to Oxford university where he obtained degrees in modern history and

theology. He did his national service in the RAF, including active service

in Malaya. In 1955, he came to Leicester to become vicar of a the parish

covering St Matthews Estate and. in 1970, he was elected to the City

Council. Following Jim Marshall’s election to parliament, he became leader

of the council from 1974-76 & and again from 1979-82. He became a

Leicestershire County Councillor in 1973 and served as leader of the

County Labour Group. He did much to move the City Council towards a

positive and inclusive approach towards the new communities then making

their home in the City.

Sources: Leicester Mercury 1st

September 1972

|

|

(I.L.P.)

In 1934, Jimmy Miller was secretary

of the Leicester Unemployed Broad Council. It was not connected to the

N.U.W.M. and claimed to be non-political and only concerned with

remedying the lot of the unemployed. It opposed the means test and

organised some local protest marches. By 1936, Jimmy was assistant secretary

of the Leicester Anti-fascist Committee. The local fascists were very

active in writing to the press and from 1934 Jimmy Miller had made the

argument against fascism on the letters pages. He was Jewish and also

active in the Co-operative movement. He was subsequently elected to the L.C.S. board.

In 1950, as a member of Leicester Peace Committee, he was

one of its two delegates who went to a conference in Warsaw. In 1950, the

British Peace Committee which

was frequently described as the "communist sponsored" was busy collecting

signatures on a nationwide petition calling on the British

Government to reopen negotiations for the prohibition of all atomic

weapons and weapons of mass destruction.

Sources: Leicester Evening Mail 19th

April 1934, Leicester Mercury 13th

May 1936, 30th November 1950.

|

|

Born:

Kilmarnock, Scotland, 18th

November 1887 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

John

Minto was born in a two-roomed cottage where he was the youngest of six

children. He and he left school at the age of 11 and was apprenticed as an

engineer and worked in the shipyards. He joined the I.L.P. in 1906 and was

active as a propagandist, being associated with

James Maxton. After

working as a ship’s engineer, he joined the Royal Engineers during the

war, working on anti-aircraft searchlights, rising to the rank of

sergeant.

After a period of unemployment he

came to Leicester in 1919, where he was again out of work for six months.

During this time he became secretary of the unemployed committee and with

Jack Binns published “The Unemployed Workers’ Bulletin.” (no copies

are known to exist)

He was elected to the Town Council

for Newton Ward in 1922 and continued as a City Councillor until 1945. He

was elected Lord Mayor in 1944. During the 1920s, he stood three times as

Parliamentary Labour Candidate for, but was defeated each time by narrow a

narrow margin.

He was a “fluent and convincing

speaker and spent twenty years as a lecturer on Literary and Historical

matters..” He was active in the Socialist Sunday School movement and

in the Left Book Club during the 1930s. He became leader of the Labour

Group in the early 1950s and was chair of the Watch Committee in the mid

1950s. He worked as an engineer for the LCS maintenance dept. for most of

his time in Leicester.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 14th

March 1924, Leicester City Council, Roll of Lord Mayors 1928-2000, Howes,

C. (ed), Leicester: Its Civic, Industrial, Institutional and Social Life,

Leicester 1927

|

| |

Born:

Leicester, February 13th 1880 died: February 1958 (I.L.P.&

Labour Party)

Albert Monk attended Lethbridge Road

School and left at the age of 13 to work in a boot factory for 4/6 per

week. He joined NUBSO aged 14. He was unemployed for 5 months in 1903 and

the following year left the shoe trade to work as a ‘spare’ conductor on

the old horse-cars (horse-drawn trams) and was paid 21/- for a 60 hour

week. By this time he had married the daughter of John Riley. Having

joined the old Tramway and Vehicle Workers Union, he was elected branch

secretary in 1911 and in 1913 became a full-time official. After the war

he continued as an official for the united Vehicle Workers’ Union and then

the Transport and General Workers’ Union.

He was secretary of the Trades

Council for 1916-17 and its president in 1923. He was also secretary of

the Labour Party during WW1 and was elected to the Town Council for

Aylestone in June 1921. Though was subsequently elected for Castle.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 7th

March 1924

|

| |

Born: West Bromwich,

circa 1866

After the death of her trade unionist father Henry

Wright, Angelina Wright’s family returned to Leicester, c1885. She married

and had several children. When the First World War came, it found a

determined and consistent opponent in Mrs Moore. During the food

shortages, she campaigned to get the Food Control Committee to institute a

fairer system of rationing and transferred he interests to the world of

politics. She became active in the Women’s Section of the Labour Party and

won a seat on the executive. She was active in support of George Banton’s

election campaigns and became secretary of the Spinney Hill I.L.P. She was

also active in the Co-op Women’s Guild and was elected to the L.C.S board.

Sources: Census returns, Leicester Co-operative Magazine

|

| |

(I.L.P.& Labour Party)

G.W. Moore was a member of Board of

Guardians and in 1908 became its first Labour chairman. We was of the view

that the guardians' powers should be passed to local authorities.

He was a stonemason by trade and was elected to the Town Council for Abbey

ward in 1909 and resigned in 1910. This followed his appointment as clerk

of works building an extension to the Council's Belgrave power station

which provided power for the trams. He was Vice-chairman of the Labour Representation

Committee 1903-1907 and its financial

secretary 1907-1910.

George Moore was either a member or active supporter of

the Women's Suffrage Society (Suffragists) and was campaigning on their

behalf in 1906.

Sources: Leicester Daily Post 7th December 1906, 17th April 1908, 9th

July, 30th September 1910

|

|

Born: Leicester, c1899

Horace Moulden was born in Leicester

and left school at the age of 13. After spending a year in a drapery

store, he entered Hall and Earl’s hosiery factory to learn ‘fleecy’

knitting in 1913. Trade was booming and his apprenticeship was

consequently a short one. Within a month he was working a full twelve-hour

shift. In the following year he left to become a knitter at Stibbe’s

factory and, excepting four years’ war service, stayed there until his

election to the Leicester Hosiery Union secretaryship thirteen years

later. His qualities as leader were soon recognised. In 1921, he became

the collector and shop steward (although the term was not used then) at

Stibbe’s. Two years later he was elected to the executive of the Leicester

Union and in 1927, following Chaplin’s death, he became one of the

youngest trade union secretaries ever appointed in the industry.

He was described as a strikingly

handsome man who was at ease in any company and looked every inch a

leader. He was a fine orator who could apparently sway

any audience.

During the 1930s he attempted to

bring all the hosiery unions together into a national union, but the

attempt failed. In 1944, a second attempt succeeded and a National Union

was formed. He was general president of the new National Union of Hosiery

workers from 1945-1963.

Sources: Richard Gurnham, 200

Years, The Hosiery Unions 1776-1976

|

| |

Born: India,?

died ? (Labour Party)

In 1948, Tamil Mukherjee

came from India

to study

the Boot and Shoe trade at the Leicester College of Technology and

Commerce. His grandfather had been a barister in Delhi. He was delegate to

the Trades Council

from the

National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives and in 1958 became its

president.

He was a buyer for Freeman, Hardy and Willis, Ltd. He is also referred to

as R. Mukherjee in some press reports.

Sources: Leicester Evening Mail, 22nd January, 7th

May 1958.

|

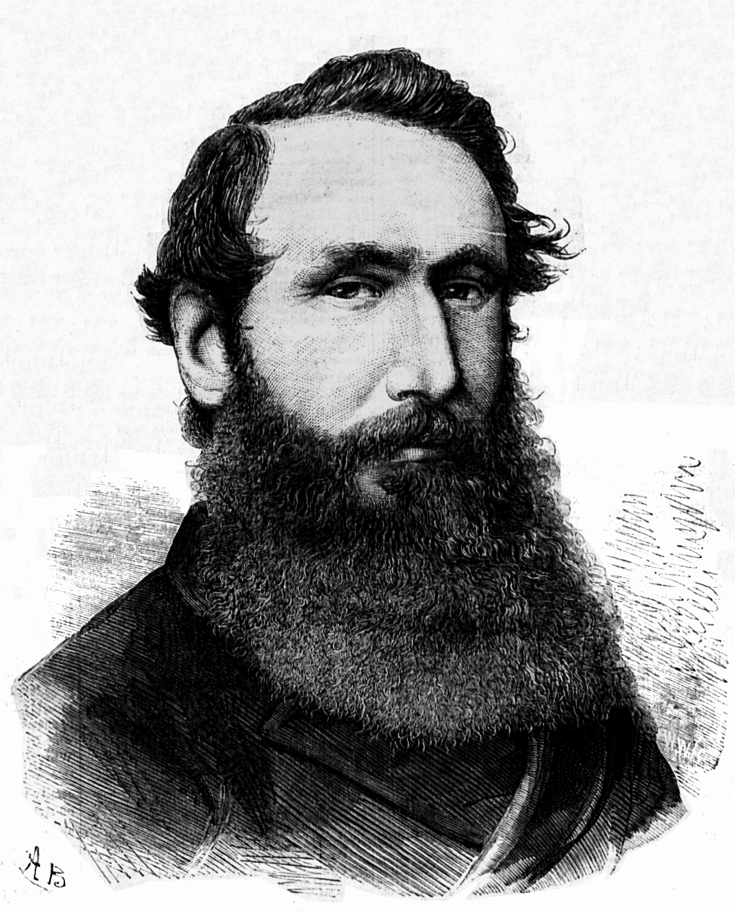

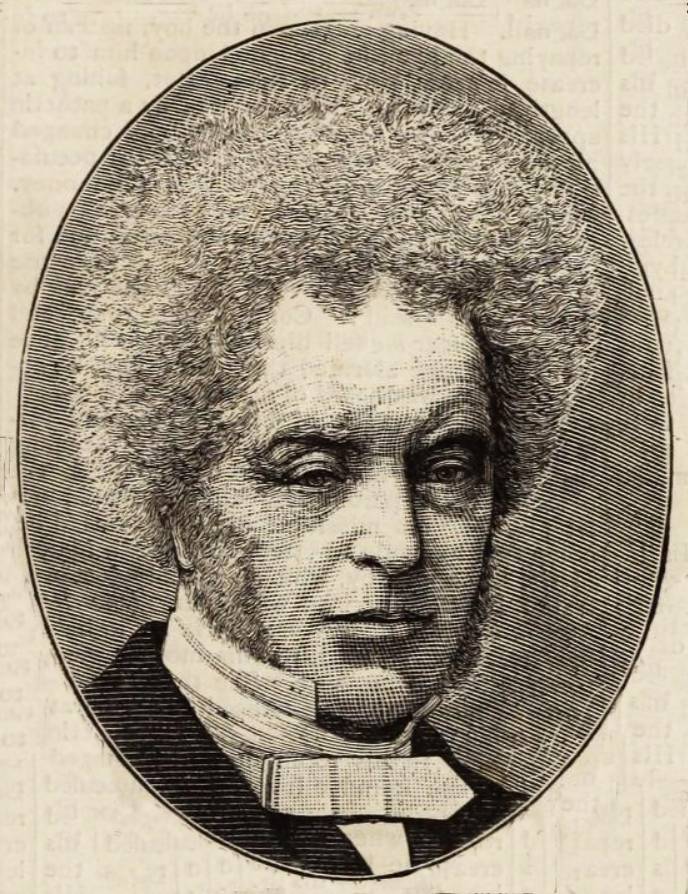

Anthony Mundella MP in 1874 (The Bee-Hive) |

Anthony John Mundella

Born: Leicester, 28th March 1825, died 21st July 1897

(Chartist and Liberal Party)

Mundella's political career as a Nottingham councillor, Sheffield MP and

cabinet minister are dealt with

elsewhere. This

article deals with his early life in Leicester.

Mundella was

the son a refugee. His father, Antonio (sometimes Anthony) Mundella, was a

native of Monte Olimpino, near Como in Italy, who fled to England in 1820

after an ill fated attempt to end Austrian rule.

He settled in

Leicester, where he married Rebecca Alsopp. Although Antonio was a

Catholic, Rebecca was a Unitarian

and she was employed as a frame-work knitter and lace

embroiderer. Antonio

originally set himself up as a teacher of languages, but had difficulty

finding any pupils. Rebecca taught Anthony from infancy and

from her he acquired a passion for books, to which he ascribed much of the pleasure

of his life and much of his success. He later said that he never went to

bed without reading a page of Shakespeare.

Anthony

attended the Anglican 'county school' or St. Nicholas National School whose syllabus

seemed to be that of reading the Bible aloud and of reciting English poets,

especially Milton.

In August 1832 Anthony participated in a

procession through Leicester in support of the Reform Bill and was one of

2,000 local boys who marched at the front wearing special caps and medals.

Mundella carried a banner which brought him to the attention of the school

authorities who promptly expelled him. (The Leicester Journal had

described the procession as a 'vile rabble.')

According to the Leicester Chronicle

Muddela's banner was probably a large flag

of yellow silk which bore the motto, "THE NATION'S HOPE," and

it preceded upwards of 4,000 Boys, with 600 Flags, inscribed: "An Educated

People," "Ours and our Fathers' Rights," " Learning is a Sceptre," "

Ignorance is a great Evil," "Let Reason rule," " Our Native Country,"

"Learn, and be wise," " Tyrants cannot take away your Knowledge."

Anthony

was readmitted after his parents had paid a

small fine.

His formal education was brought to an

abrupt halt in 1835 when his parents were forced to remove him from

school. This was due to the loss of family earnings when his mother lost

work as a result of her failing eyesight. Aged 10, he was employed as a

printer's devil for a local firm and after

nearly two years of drudgery, at

the age of eleven,

he was apprenticed to Mr. Kempson, the hosiery manufacturer.

He attended classes

at the Leicester Mechanics'

Institute, stole time from his hours to study and completed his

apprenticeship in his 18th year.

Contemporary

accounts stress Mundella's humble beginnings and the part his mother

played in sustaining the household through her by her skill and taste in

lace making. Although they mention that his father had no trade or

profession and had intended to enter the Church, they neglect to mention

that Antonio ran a pawnbrokers shop in Orchard Street in the heart of

Leicester's slums. During the 1840s, he was often a witness in court, when

his customers were prosecuted for selling him stolen goods. (Antonio was

an active radical and in 1857, he was remanded in custody for threatening

to shoot the whig John Dove Harris who was standing against the John Biggs

and Joshua Walmsley. Dove Harris was regarded as a renegade. Antonio

also got in trouble for his savage dog and for drunkenness)

Aged 12 or 13 Anthony he was a scholar at Harvey Lane Sunday school, where

his superintendent remembered him as a red hot republican. His father's history and sufferings

had made him a

hater of oppression and misgovernment and that must have influenced the

young Mundella. At the height of the Chartist agitation in 1842, Anthony attended Cooper's lectures and readings at the Shakespeare Room in

Humberstone Gate. He also attended debating classes at the All Saints Open

and at the Gallowtree Gate chapel. (now Boots) At the age of fifteen, he made his first political

speech in support of the Charter. Thomas Cooper

recalled:

a handsome

young man sprung upon our little platform and declared himself on the

people's side, and desired to be enrolled as a Chartist. He did not belong

to the poorest ranks, and it was the consciousness that he was acting in

the spirit of self-sacrifice, as well as his fervid eloquence, that caused

a thrilling cheer from the ranks of working men.

Cooper had a

strong influence of Mundella and at the age of fifteen, had already

heard Radical and Anti-Corn Law songs of his own composition sung in the

streets. Mundella had a mighty bass voice which was a singular advantage

to any politician in the days before microphones.

In 1845, he married Mary (d.

1890), daughter of William Smith, formerly of Kibworth Beauchamp in

Leicestershire. The marriage lasted forty-six years.

At nineteen he was engaged as a manager by Messrs. Harris &

Hamel. Mundella's

Chartist sympathies were shared by his employer William Harris and in 1848

Mundella emerged briefly as a local Chartist leader. At a Chartist meeting

held in the Amphitheatre, he seconded John Markham's motion calling on the

Queen to dismiss her Ministers and call to her council persons who would

make the Charter cabinet question. Both Harris and Mundella supported the

political accommodation between Biggsite middle-class radicals and Chartist

movement.

In 1848, aged 23, Anthony was taken into partnership by Messrs. Hine &

Co., hosiery manufacturers in Nottingham, and moved from Leicester.

In

1845, he married Mary (d.

1890), daughter of William Smith, formerly of Kibworth Beauchamp in

Leicestershire. The marriage lasted forty-six years.

The extremely short Mundella

Street off Kimberley Road was named after him sometime in the early 1890s,

whilst the Mundella School, Overton Road, was opened in 1939. Wood and

metalwork rather the Shakespeare seem to be at the core of the curriculum.

Sources: Leicestershire Mercury 22nd April 1848,

26th May 1939, Leicester Chronicle 25th August 1832, 29th April 1848, 7th

& 28th March 1857, 24th July 1897, Leicester Journal 23rd & 30th July

1897, Leicester Daily Post 28th July 1897, The Bee-Hive 4th April 1874 Thomas

Cooper: The Life of Thomas Cooper, 1872.

|

|

Born: Leicester, June 1872,

died March 1923 (I.L.P. & Labour Party)

John

Murby came from an old Aylestone family and went to St. Martin’s school,

leaving at the age of 14. (He went to school with the W.E. Hincks who was

later a Liberal councillor) After working for a printing firm where he was

injured in an accident, he became a clicker. Following a period of

unemployment, he found work at the C.W.S. Wheatsheaf factory. He stayed

there for two years before working for the Co-operative Self Help Boot and

Shoe Works in Aylestone Park, where he became a member of the committee.

Murby came from a non-conformist

stock and was an active Wesleyan and secretary of the bible class at

Aylestone Road Chapel. He came in contact with W.E. Wilford, who

introduced him to Tolstoy and he joined the I.L.P. in 1903. Together with

him they founded the South Leicester Labour Church, which was described as

one of the most successful Sunday meetings in the town; Murby was

president. He was described as being “powerfully religious, but

socialism adorns his religion……Like so many Socialist speakers, his

oratorical skills have been forged on the anvil of necessity. If you

survive, no audience has terrors for you. Murby survived.”

He was elected as a town councillor

for Castle ward in 1909 and soon became a prominent figure in the local

I.L.P, being its chairman in 1913-16. Following refusal of the Labour

Party nationally to support the candidature of

Geo Banton for

parliamentary by-election, he gave his support to the British Socialist

Party’s candidate Hartley. He spoke against Britain's entry into

World War One and was active in the local branch of the Union of

Democratic Control.

In 1917, he became the Midlands representative

on I.L.P. NAC (executive). He was a member of NUBSO No 2 branch. He later

worked for NUBSO as manager of its National Health Insurance Dept and he

held this position until his death. His wife Mrs J.W.

Murby was elected to the Leicester Labour Party Executive in 1915, they

were married in 1898

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 26th

October 1907 & 12th October 1912

|

%20JP%20Mursell%20New%20Hall.jpg)

J.P. Mursell

holding a stone thrown by a supporter of Thomas

Cooper at the New Hall (former lending

library) during a Complete Suffrage meeting. (1886) |

Born: Lymington, Hampshire c1799, died: 1885

James Mursell succeeding Robert Hall

at the Harvey Lane Chapel in 1826. He was later minister at the Belvoir Street Particular Baptist Church.

During the agitation prior to the 1832 Reform Bill he firmly established his radical

credentials . He

ministered in the town for fifty years, during which time he married three

times. Mursell was one of the promoters of the old Mechanics' Institute,

which provided lectures, education and books to working people when when

free libraries were undreamt of. He then had distinguished himself in 1837 by his efforts to secure

financial support for the Proprietary School, (now the New Walk Museum).

which was the Nonconformists' answer to the Anglican Collegiate School in Prebend Street.

Mursell was a staunch political

Radical. In 1838, wrote a series of letters on "The rights of

labour" and was an advocate of 'Negro' emancipation, the repeal of

the corn laws, the abolition of Church-rates, and the disestablishment of

the State Church. He was one of the founders of the. Liberation Society,

founded in Leicester and known also as the 'Anti-State Church Society.'

He was also one of the originators of the Leicestershire Mercury, and one

of its frequent contributors before it merged with the Leicester

Chronicle.

Mursell was one of the few

prominent middle-class men in Leicester to declare his sympathy with the

Chartists. According to Thomas Cooper,

he told a Chartist meeting: “Men of

Leicester, stick to your Charter! When the time comes,

my arm is bared for Universal Suffrage!”

Apparently he never attended another Chartist meeting, though he was

eagerly looked for and the cry “Where’s Parson barearm?” was heard

subsequently at Chartist meetings.

In March 1842, he became one of the founders of Leicester

Complete Suffrage Association which represented the left wing of largely

Baptist elements amongst middle class radicals.

Thomas Cooper was extremely hostile to the

Complete Suffragists and when they engaged Henry Vincent to speak in July 1842,

Cooper successfully disrupted the meeting. Cooper's

Shakespearian Chartists occupied the platform and attempted to put

Thomas Beedham

in the chair in the place of Mursell, however the Complete Suffragists resisted.

A rowdy

stalemate ensued: the ladies were asked to leave

and Henry Vincent did not deliver his lecture. Further rowdy scenes

followed at the close of the meeting, 23 panes of glass were broken by

stones and people assaulted. Vincent gave his lecture the following night

at a ticket only event. Mursell regarded Thomas Cooper as an

infidel and

described the Shakespearian Chartists as “the lowest rabble in

Leicester with Cooper at their head.”

In 1845 the Harvey Lane chapel became a school room and

the Harvey Lane congregation, led by the Reverend Mursell, moved to a new

Baptist chapel in Belvoir Street (the Pork Pie

Chapel) which had been designed by the leading architect

Joseph Hansom.

In 1863, during the American Civil war a local

Emancipation Society was formed to support Lincoln's commitment to abolish

slavery. Although Mursell had been involved with the anti-slavery movement

from the 1830's, he declined to give his support claiming that he did not wish to favour

either North or

South. This was most likely in deference to the preponderance of

Confederate Baptists.

Sources:

Leicestershire Mercury,

14th February 1863,

Leicester Chronicle, 6th

March 1886, A. Temple Patterson,

Radical Leicester,

Leicester 1954, The Christian Herald and Signs of Our Times 18th November

1886

|

| |

|

|

Back to Top |

| |

© Ned Newitt Last revised:

September 14, 2024. |

| |

Bl-Bz

Leicester's

Radical History

These are pages of articles on different

topics.

Contact

|