|

R

|

|

|

Born: Edinburgh? died Leicester c1960? (Socialist Labour Party & Communist Party of Great Britain)

Dave Ramsay was a pattern maker by trade and a member of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. During World War One, he lived in Baker Street and was a member of the Socialist Labour Party. The S.L.P. had most of its membership in Scotland and it is possible the Dave Ramsay was born in Edinburgh and had come to Leicester to work. Of the parties to the left of the ILP, the S.L.P. was much more antagonistic to the Labour Party, than the British Socialist Party which sort to become an affiliated organisation.

Dave Ramsay was an anti-war activist and was fined £100 on 11th May 1916 for attempting to prejudice recruiting to the army. By the end of the war, Ramsay was part of the inner circle of activists involved in building 'workers' committees’ across Britain, based on the the model of the Clyde Workers Committee, though there is no evidence of such a movement in Leicester.

In November 1918, he is described in British police files as 'advocating revolution with machine guns' at a meeting with Sylvia Pankhurst on the platform. In 1919, he was the national treasurer of the "Hands Off Russia" movement movement designed to stop the British military intervention. He was also the National Treasurer and Organiser of the National Council of Shop Stewards and Workers Committees. It is probably that by this time he was using Leicester as a base for his national political activities.

A speech he gave to a large Daily Herald League rally in a Croydon cinema led to his arrest in Leicester on the night of February 16th 1919 under the Defence of the Realm Act. Five policemen called at his house and he was taken to Bow street Police station in London. He was charged with acts likely to cause mutiny and disaffection in the forces and civil population. He was alleged to have told the meeting that "I am proud to call myself a Bolshevist." According to the prosecution, he stated that he was engaged in spreading the principles of Bolshevism, and wanted the workers of this country to emulate the example of 'our Russian and German comrades' in bringing about revolution in this country. They claimed that because the 'master class' would use every means to uphold capitalism, he was prepared to use every means from the bomb to the ballot-box. He was sentenced to six months' imprisonment in March 1919. When sentence was pronounced the press reported that his supporters sang The Red Flag and as he was removed from the court, there was a noisy demonstration.

Dave Ramsay became a prominent figure in the early years of the British Communist Party. In 1920, the British Home Secretary consulted ministerial colleagues as to whether to allow Ramsay a passport. Secret police reports showed that he had been present at meetings in Grosvenor Square, held to protest against UK support for the Polish offensive against Soviet Russia. Ramsay was recorded as saying that if workers were called up for the army they should not refuse, but should take rifles but would “know what to do with them."

He was a delegate the 2nd Congress of the Communist International, which was held from July 19th to August 7th 1920 in Soviet Russia. After 1926, he became the Scottish Organiser of the Communist Party and was Harry Pollitt’s election agent in the Seaham constituency during the 1929 general election. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Ramsay was kept under constant surveillance. Although he is believed to have died in Leicester, it seems that much of his political activities took place outside the City.

Sources: Matthew Richardson, Leicester in the Great War, Lancashire Evening Post, Yorkshire Evening Post, 8th March 1919, The National Archives

|

|

Born: c1841? Exhall, Warwickshire? (First International)

E.W. Randle was an elastic web weaver and was Secretary of the Leicester branch of the First International. The local branch attempted to get the local Republican Association to affiliate to the International in 1873.

Sources: Midlands Free Press 22nd February 1873, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

(British Socialist Party, Social Democratic Party, Labour Party)

Frank Rands opposed the I.L.P.'s pre 1914 electoral pact with the Liberals. When the I.L.P. stood no candidate in the 1913 parliamentary bye election, he was active in support of Hartley the British Socialist Party candidate intending to ‘smash MacDonaldism and stand for Socialism.’ That year, Rands stood as a Socialist candidate for West Humberstone in the Council elections when the I.L.P. again stood no candidate in deference to the electoral pact. He advocated a municipal house building programme, taking back the land on the outskirts of town to establish colonies for the unemployed and gas to be supplied at cost price.

In October 1914 he proposed that the Trades Council send a representative to the recruiting committee which was heavily defeatd. (40 to 14) In the early 1920s, he was a member of the Social Democratic Party which was a remnant of Henry Hyndman's pro war faction of the B.S.P. which was eventually absorbed into the Labour Party. In the 1930s, he was active in the Labour Party and was its president in 1935 as well as being president of Spinney Hills Labour Party. He worked as an engineer at the the Poor Law Institution of Swain Street. (the former workhouse) In 1951 he told the Trades Council:

"The buses ought to be run on the rates, the same as water is. You would be able just to get on a bus and ride. It might seem foolish at first, but there are other ways of paying for them besides fares. There would be no tickets to be printed, no people to give them out and no inspectors. It would do away with quite a lot of surplus labour."

Sources: Justice 7th August 1924, Leicester Daily Post, 14th October 1914, Leicester Daily Mercury 20th June 1913, Leicester Chronicle, 18th October 1913, Leicester Pioneer, October 31st 1913, Leicester Evening Mail 15ht February, 4th Match 1935, 8th April 1951

|

|

Born: Sept 1923, died: June 1986

Harbans Ratoo was a Sikh businessman who had come to Leicester in the late 1950s. He was prominent on the Community Relations Council and President of the India League. In 1972, the British Asian Welfare Society was set up to assist the arrival of refugees from Uganda and Harbans Ratoo became its president. Its office was behind a cinema in Belgrave Gate which he owned. However, it was not long before Mr Ratoo was being seen as having accepted the City Council’s policy of advising the refugees not to come to Leicester. He was strongly criticised by the local branch of the Indian Workers Association (GB) for ‘scare mongering’ and ‘opportunism.’ He was later adopted as a Labour candidate in the local elections.

Sources: Leicester Mercury 10th June 1986, Valerie Marett, Immigrants Settling in the City, 1987

|

|

(I.L.P.& Labour Party)

She became the first woman on the Executive of the Leicester Labour Party in 1913.

|

|

Born: c1865 Leicester (I.L.P. and Labour Party)

A.H. Reynolds was orphaned at an early age and he was left in the charge of Henry Thomas Chambers, JP, alderman and later mayor. Unlike many others in the I.L.P., he received the best possible education, going to a private school on New Walk and to the Mill Hill House School on London Road. After working in the printing trade, he worked as a clerk for the Corporation’s Water Works Dept. for 17 years. He left to become manager of the New Pioneer Publishing Society, who published the Leicester Pioneer.

He was very active in the temperance movement, but he began to realise that temperance alone was not the answer to social problems. He attended the Wycliffe Adult school and was influenced by the election campaigns run by Joseph Burgess. He was elected to the executive of the I.L.P. and general committee of the Labour Party. He was apparently a speaker who was much in demand. He was a director of the Temperance Hall Company and chairman of the executive of the Leicester Temperance Society.

He was elected as town councillor for Newton ward 1909 and 1912 and was Ramsay MacDonald’s agent in the 1910 election. Following the refusal of the Labour Party nationally to support the candidature of Geo Banton in the 1913 parliamentary by-election, he offered his services to the British Socialist Party’s candidate Hartley.

Although close to Ramsay MacDonald , Reynolds did not support MacDonald's stance on the war. By this time, it seems that Reynolds was not liked or trusted by the leading members of the local I.L.P. However, it was not until 1916, that MacDonald dismissed him as his agent. Reynolds appears to have remained at the Pioneer, which may explain why the "Free Man" was launched by the local I.L.P. in 1917

Sources: Yorkshire Herald, 24th June 1913, Ramsay MacDonald: The Leicester Years, John Hinks 1996.

|

|

Born: 24th August 1906, died December 1995 (Communist Party)

Johnny Rice was the son of a militant suffragette. In 1936, he was arrested by the Gestapo whilst working in Germany and was released following the intervention of Anthony Eden. He worked in France and America as a waiter and joined the Communist Party in 1939. He worked for the gas board as a meter reader and was the steward at the Trades Council for many years. He was a Communist Party candidate in local elections in Castle ward in 1960 and other subsequent elections through to the 1970s. He was a familiar figure in Gallowtree Gate on Saturday mornings where he sold the Morning Star. He was a member of the British Soviet Friendship Society and was on ‘pro soviet’ wing of the Communist Party.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, May 1960, author’s personal knowledge

|

|

Born: 25th March 1863 died: 4th October 1942 (S.D.F., I.L.P.& Labour Party)

Freddy Richards was born in Wednesbury, Staffordshire, the son of a commercial traveller who was a Conservative. Freddy Richards was educated first at a Church school and then at a Board school, and began work as a half-timer at the age of eleven. A year later his father died and the family - mother, four boys and a girl - found themselves poor. Freddy then went to work full-time, and had a variety of ill-paid jobs until he saved enough money to pay an apprentice's premium to become a boot-laster in Staffordshire. He then moved to Leicester and joined the National Union of Operative Boot and Shoe Riveters and Finishers (later the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives) in 1885. He soon made his reputation as a vigorous and lively critic of the union establishment. He led a series of successful unofficial strikes in 1889 and challenged the Liberal leadership of the NUBSO.

He was a keen student of Tom Barclay’s socialist classes, sharing his teacher’s love of Ruskin. Freddy Richards was a committed socialist by 1889. At that time he was a member of the S.D.F. He became a delegate to the Trades Council in 1892 and in July 1894 helped found the I.L.P. in Leicester.

During the early 1890s, he strongly supported the ideals of co-operative production and advocated the use of union funds to set co-ops up. This was opposed by the union’s national leadership. However, in 1893, the St. Crispins factory was started with £1,000 of interest free capital given by local NUBSO branches. Although, Richards with Matin Curley and Edward Clarkmead lobied for more union funds for the venture, the co-operative failed in 1895. Whilst Richards, stopped lecturing branches on the Industrial Co-operative Scheme, he remained involved with its successor, the Self Help Co-operative for many years. In the 1920s, this was one of 16 boot and shoe factories owned and controlled by the workers employed.

Richards was strongly opposed to the principles of arbitration in his trade, and agitated within the union for a political commitment to an advanced programme including large-scale nationalisation.

In December 1894, Richards became the first Independent Labour councillor to be elected to the Town Council in 1894 for Wyggeston ward. Based on the I.L.P. programme approved on October 22 1894, during the election he advocated:

-

That councillors to be paid an allowance, that aldermen should be abolished and that magistrates should be elected.

-

That the Borough accounts should be published and reporters should have the right to attend council committee meetings

-

The municipalisation of tramways and ‘busses

-

The building of healthy council houses and the abolition of gas meter rents

-

The ending of contract labour by the council and the introduction of direct labour employed at TU rates

-

The establishing of municipal farms and gardens to absorb the unemployed

-

An 8 hour day for all council workers, a minimum wages for workers and a maximum wage for officials. All council workers to be placed on an equal footing with regard to holidays

-

The opening of municipal bakeries and council runs depots where coal and other items can be sold to the public at a low cost

-

Opposition to compulsory vaccination

-

That Labour newspapers be placed in the Town's free libraries

He was elected junior vice-president of the important Leicester No. 1 branch in 1892, vice-president in 1894, and president in 1897. In 1893 he had become a permanent official of his local branch and by 1899 was on the national executive council. Richards played an important part in persuading the union to affiliate to the Labour Representation Committee.

Mr Richards’ pale face and sharp almost ascetic cast of features, combined with his somewhat slender build, fail to convey to the stranger the virility and nervous energy which he possesses. Yet Mr Richards is full of activity and as the Town Council is fully aware, is a born fighter. For biting sarcasm and stinging satire he is, when occasion calls, a terror to his opponents.

In June 1900, J. Ramsey MacDonald was invited to address the annual conference of the Boot and Shoe Operatives in Leeds and it was Richards who proposed the motion that the membership should be balloted on the question of affiliation - the result of which was affirmative, although the total vote was small. When Richards, the leading ILP member in the union, stood for the general secretaryship of the union in 1899 he polled 3139 votes against 4501 for the Lib-Lab candidate, W.B. Hornidge. Richards was appointed a full-time national organiser in 1904 but he resigned during the following year, giving as his main reason the serious difficulties involving his own Leicester branch. But a new career was about to begin, when he was adopted by the Wolverhampton Trades Council as the L.R.C. candidate for Wolverhampton West in 1903. At the election, on 15 January 1906, Richards just won the seat with 5,756 votes against 5,585.

Richards' four years in the House of Commons followed a common enough pattern. He was elected a Junior Whip for the Labour group. He was a good debater and controversialist and he immersed himself in the minutiae of parliamentary business, the full detail of which he recounted in his union's Monthly Reports. His general attitudes, however, were becoming less radical and more moderate, and within a year of his election he was being vigorously criticised by the active Socialists within his own union.

During the 1900s, Freddy had mellowed in more senses than one; in physical appearance as well as in thought and attitude. He was counted among the first dandies of the trade union movement. Bow-tie, carnation in his button-hole, white waistcoat and white spats were the keynote (together with what was known in the Labour movement, with affectionate derision, as an ‘anarchist’ or straw hat). A few sneered at the ‘Beau Brummell’ of the trade unions; some derived an obscure vicarious satisfaction at seeing a Labour leader dressed more smartly than some of the employers with whom he was dealing.

He lost his Wolverhampton seat at the January election of 1910 and unsuccessfully contested the East Northants constituency in the second general election of that year. On this occasion he fought without any financial help from the union. The reason given was the Osborne judgement, but Richards was convinced there was prejudice against him by some members of the union's council, and the incident rankled for many years. He twice attempted to get back on the Town Council in 1914, but failed. In 1910, he was elected president of the union and he retained the office until 1929.

The need to increase production during World War One strengthened the union’s position, giving it a power and prestige which it had never previously enjoyed. Unlike his colleagues in the I.L.P., Richards supported the war: “I advised both my boys to join up and should have done so myself if I had thought that by doing so I could have done more good. I have sung the ‘Red Flag’ and was prepared to fight for it and kill militarism in this or any other land.” In August 1918, this pro-war stance was the reported reason for his rejection as the Labour parliamentary candidate for Northampton. It is not known why, in 1917, he declined the award of a C.B.E. for his services to the war effort. Perhaps it was a gesture towards his anti-war colleagues.

He remained a hardworking and efficient union administrator, and found no serious difficulty in containing the vigorous challenge to the established leadership of the union which came from the Minority Movement in the 1920s. He became president of the Trades Council in 1928 and retired from union work in 1929. On his retirement from union office, he was returned as Labour councillor for the Newton ward of Leicester City Council and he served for the next ten years.

He was twice married: firstly to Emma Mee (c1862-1915) in 1882, by whom he had two sons and a daughter, and then, in 1916, to Mary J. Bell, secretary of the Leicester Women's branch of the Boot and Shoe Operatives. He died at his home in Birstall, Leicester, in October 1942. He was survived by his wife, a son and daughter by his first wife and an adopted son.

Sources: Leicester Trades Council, Trade Union Congress Leicester 1903, Official Souvenir, 1903, Fox, Alan, A History of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Workers, F. P. Armitage, Leicester, 1914-1918, Leicester, 1933. 1958, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

Born: 1870 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

The first impression one gets of him is of a mild looking man in spectacles, very correct in dress and manner…he doesn’t quite look like a Socialist.

Frederick Riley was born in Stoney Stanton. Both his parents were of Irish extraction and his father was a framework knitter. He came to Leicester at the age of 15 and worked as a postman and then as a clerk. He became an officer of his union in 1902. He was elected to the Town Council in 1906 and was for five years, chair of the Arts, Libraries and Museums Committee. According to the Leicester Pioneer, he had a notable interest in and knowledge of artistic matters and a private collection of pictures. He was the Labour Party parliamentary candidate for South Leicester in the khaki election of 1918. However, as a clerk in the post office he was barred from standing for parliament and consequently had to resign his job in order to become a candidate.

|

|

Born: c1852 died: April 1937 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

John Riley was born in Stoney Stanton and had very little education as his family could not spare him to go to grammar school. His father was a stockinger and he worked with him as a winder as well as working on the land. He came to Leicester and worked as a framework knitter and in Cooper and Corah’s hosiery factory. When he went to work at a factory in Canning Place, there were some very old men there who had belonged to the Chartist movement and had walked the streets with Thomas Cooper. Riley had a love of books and although some of these old Chartists could neither read nor write, one of them, Robert Bingley, advised him to read Cobbett. He was also advised in his choice of books by John Newell who also insisted on him going to evening classes at the Working Men’s College. He was later able to read Virgil, Caesar and the New Testament in Latin. He was active in the hosiery union and in his early days used to meet with kindred spirits in the Red Cow where Tom Barclay was a visitor.

Riley was attracted by the radicalism of P.A. Taylor MP and was an active supporter of temperance, a member of the Band of Hope Movement and the adult school movement. He joined the I.L.P. in 1894 and won Aylestone as Labour candidate in 1905 after campaigning strongly on the right to work. Unfortunately his health forced him to retire from the council soon after. When he had recovered from his illness, he was elected to the Executive of the Hosiery Union and was president for three or four years. He became president of the Trades Council in 1918. He presided over the May Day meeting of 1918 which was disrupted by jingoistic supporters of the war and never forgot the spectacle of the faces of men and women “so distorted almost out of recognition by hatred and passion as on that day.” He was elected to the board of L.C.S. c1916 and served for at least 10 years.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 22nd February 1918

|

|

Born: March 1895, died Leicester April 1977 (Labour Party)

Helena Roberts was Jewish by birth but Christian by conversion and she had a long career as a Labour councillor in Stepney. She was first elected in 1925 for South East Ward Stepney which covered the Mile End area. She was a seasoned public speaker, speaking every Friday night on the streets of Hackney on a platform which her husband set up.

In 1935, she became mayor of Stepney. During the tense atmosphere of 1936, she, as mayor, sought to obtain police protection for local Jews from the attentions of Mosley's Blackshirts. In October 1936, she urged the Home Secretary (along with other mayors) to ban Mosley's march through the East End. Although she urged people to stay away from the 'Battle of Cable Street' she wrote:

The great majority of the people ot Stepney are distressed and anxious at the events of yesterday. I have heard, in my tour of the streets where the trouble was, of innocent people who got in the way of police batons. Personally. I think the people were splendid. "

"With feeling running high and as the Mayors of the five East End boroughs made abundantly clear to the Home Secretary, people were driven to a pitch of desperation, it was a moral triumph for the people of the East End that things were not much worse."

"The Home Secretary and the Commissioner of Police ignored the signatures and the appeals of the Mayors, who knew what was likely happen. Upon them .... must fall the blame for the disturbance. I hope devoutly that shall never have a repetition of yesterday and that the youth of Stepney will do nothing to inflame passions which will subside if only the peaceable hardworking people of the East End are left peace.'

She later proposed a committee of inquiry into allegations of police brutality against anti-fascists and was active in support of Republican Spain.

On Stepney Borough Council she was chairman of Stepney Health committee for 20 years and served on the housing, maternity child welfare finance and parliamentary Committees, and was deputy leader of the council. Before her retirement, she was a managing clerk to a firm of solicitors. She was awarded the OBE in 1949 for 25 years service to local government.

Helena Roberts came to live in Leicester in 1960 because her daughter Babette had become a lecturer in history at the University of Leicester. She was elected to Leicester City Council in 1961 for Newton Ward. (New Parks) and was chairman of the Housing Committee from 1963-65. In 1965, she reached the age limit for Chairs of Comitte and stood down and was succeeded by Ted Marston. In 1964, the Housing Committee introduced a direct labour scheme to build houses and it was subsequently awarded the ill-fated contract to build St Peter's Estate. This was terminated in September 1969. Cllr. Roberts stood down from the council in 1970.

She was chairman of the governors at the City of Leicester Training College, Scraptoft from 1961 to 1976 and was on the governing body of Leicester Polytechnic. She was chairman of the governors at New Parks Boys’ and Girls’ School.

Helena Roberts House, Kingfisher Avenue, Charnwood, retirement housing, was subsequently named after her.

Sources: Weekly Dispatch (London), 4 October 1936, Daily Herald, 6 October 1936, Leicester Chronicle, 10th September 1965, Leicester Mercury, 2nd March 1961, 9th June 1964, 25th March 1970, 29 April 1977

|

|

Born: Liverpool 1947, died 2023 (Labour Party.)

James (Jim) Roberts was born into a working class-family in Liverpool and by 1948, his family had moved to Sutton-in-Ashfield in Nottinghamshire. When Jim was fourteen, the family moved again, this time to Leicester where he went to Alderman Newton’s School.

Jim did not stay on at school and left to work for Dolcis shoes. By the mid-1960s, he was working at Fenwick’s and then at a number of other Leicester stores where he used his talent for design in creating window displays. After working in the Bahamas , Jim returned in the early 1970s to work in the museum service where he worked at Belgrave Hall creating displays for the Schools Service.

In 1973 Jim became a technician at the relatively new Department of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester. Throughout an almost 50-year career in and with the School, Jim’s role changed shape, particularly as the use of digital technology grew.

Jim retired from his full-time role in the School in 2011, though he continued, to work as Production Editor of the online, journal Museums & Society and the University of Leicester Jobs Desk, ensuring that neither journal were placed behind a pay wall.

Jim was very proud when a ‘Jim Roberts Prize’ was created, to be awarded for an outstanding research project relating to museums and social justice or positive social change. He always made sure that he contacted the winner each year to congratulate them.

Closely intertwined with his work in the School, were his politics and political life. His wife Marea recounts an early experience of attending a talk by Edward Heath with Jim in Leicester’s De Montfort Hall in 1970 - Jim shouting back to Heath, calling him out on his policies and the economic decline that was causing such hardship at the time. Jim joined the Labour Party in 1973 and within months was chair of his local Labour Party branch. He unsuccessfully stood for election to a local District Council seat in 1979 and in 1981 he was elected to the County Council for Belgrave. From 1986 Jim represented Stoneygate as a County Councillor, working in this role for the next 12 years. In 1987, Jim stood in Blaby as Labour’s Parliamentary candidate against the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson.

On the County Council, the Labour Group elected him to various Chairs including Employment (then called ‘Manpower’) and Arts in Education. He became spokesperson for Social Services and in the ‘hung council’, he almost always chaired the meetings. He appeared at several national press conferences during the time of the ‘Beck Enquiry’ when Frank Beck a former social worker and Officer -in- charge of several Leicestershire Children’s Homes was convicted of sexual abuse.

For many years, Jim was supported by the left of the County Labour group to become leader. However over many years, but never achieved this as the more moderate members continued to support Jim’s good friend Martin Ryan. He did however become Deputy Leader. In 1995 he became Vice-Chairman of the County Council and in 1996 Chairman of the County Council.

Committed to his socialist principles, highlights that mattered to Jim over this time included his work to rewrite the County Council’s Equal Opportunities Policy. Whilst Chairman of the County Council, Jim visited Mablethorpe with the Leicester Children’s Holidays charity – a charity that sends children from low income families for a holiday at the seaside. An area of work close to his heart, Jim would later join Marea on the board and become a very hands-on Chairman for several years.

Jim’s political life connected very directly with his interest in culture and his work in the School of Museum Studies. In 1995, he was elected to the Museums Association and remained a Local Authority Institutional Councillor until 1997, stepping in for a period as vice-Chair. He was a Trustee of the Haymarket Theatre and worked closely with the Bardi Symphony Orchestra. He became Chair of the City of Leicester Museum Trust and enjoyed the opportunity to purchase objects for the Leicester collections.

The re-establishment of Leicester as a unitary authority, meant that that the prospect of Labour controlled County Council receded. It also threatened to break up the County wide museum service and Jim fought very hard to try and retain one museum service for both City and County.

Sources: Marea Roberts

|

|

Born? (R.S.L.)

Robinson was the uncompromising leader of the Trotskyite Revolutionary Socialist League in Leicester in the late 30s and early 40s. His historic legacy seems to be a wrangle with fellow Trotskyites over whether the working class should demand deeper air raid shelters. (This had been CP policy since 1936) In his view: “If one favoured a deeper shelter, why not a better gas mask, a more rapid firing machine gun, a faster tank? If revolutionaries began to make concessions of this kind they might be led inexorably to improving the military efficiency of capitalism: they had to desire their own government’s defeat.”

Robinson flatly opposed any demands on the state for protection; he made this demand in midst of the blitz from the comparative safety of Leicester. A document was issued, ‘Bolshevism or Defencism,’ which indicted the Trotskyite Centre for capitulation and was the start of a long and tedious polemic.

Sources: Martin Upham: The History of British Trotskyism to 1949

|

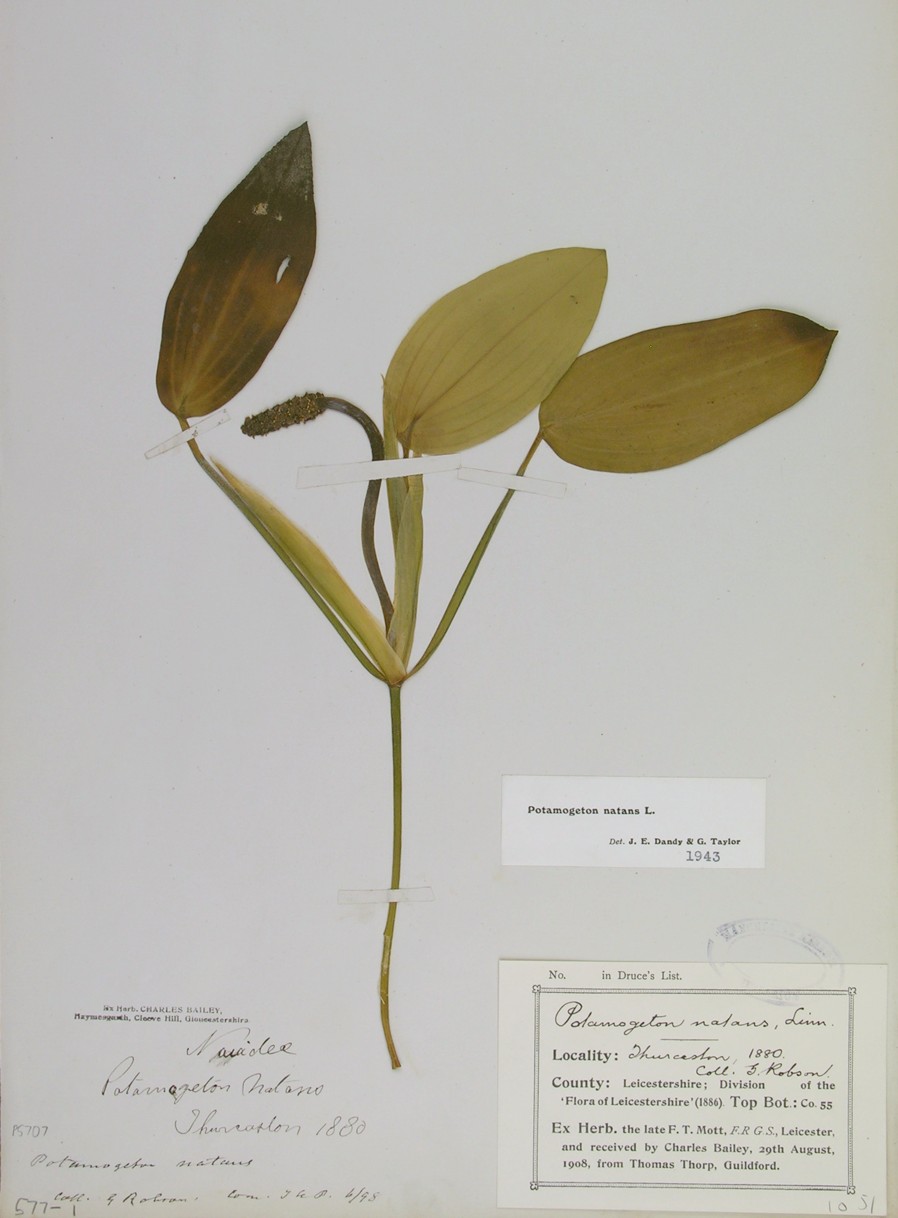

A specimen of Broad-leaved Pondweed (Potamogeton natans herbarium) collected by George Robson from Thurcaston in 1880. (Manchester Museum)

|

Born: Leicester or Leicestershire circa 1837, died: 4th July 1889 aged 46 (Socialist League)

George Robson was a framework knitter by trade and lived in Cranbourne Street. He was a socialist, secularist and friend of Tom Barclay and Joseph Dare the Unitarian social missionary. In 1876 Robson said that he was:

"one of many whom Mr. Dare had literally 'picked out of the gutter,' and through his help he had washed off some of the dirt, and if he had the good fortune to become quite clean he should owe it all to Mr. Dare."

Robson worked at Corah’s with Tom Barclay and they were both supporters of Charles Bradlaugh. In the 1880s, Robson was an activist in the Leicester Amalgamated Hosiery Union.

From the 1870’s, Robson was an enthusiastic naturalist who made a complete collection of specimens of Leicestershire moths, butterflies, beetles and plants which found their way into the Museum’s collection. He won the botanical prize two years running at the museum. In the Midland Naturalist of 1879, Robson was described as ‘a Leicester stocking-maker...who has found means for self-cultivation while bringing up a large family on the earnings of his frame. There are probably not a dozen men in Leicester of all classes who know as much about the Natural History of their district as he does...’

In the same magazine, Robson published records of 40 water beetles. He wrote that ‘Hunting the beetles, under the invigorating influences of fresh air and sunshine was all pleasure.’ Robson donated 92 water beetles to the Leicester Museum in 1877 and a collection of Rove Beetles (Staphylinidae) in 1879. From 1875-1885 he gave 1,200 species of plants to the museum. One collection, consisting of 400 species, was wholly Leicestershire. The other collection, containing 800, was partly Leicestershire. His dried plant specimens are in the Manchester Museum and Birmingham University collections.

The collections were very probably a bye product of the Sunday walks of local radicals which he also commemorated in poetry. In 1876, his book: The Twentieth Walk-out of All Saints' Open Discussion Class, and other Poems was published in Leicester. It was given a very favourable review in the Leicester Chronicle:

We had been told that its author was a poor working-man: that he was born in the most forlorn and wretched quarter of our old town; that he never had a single day's education in his life, and yet we found that his verses evince a capacity for philosophising, a refinement of taste and a power of expression, which prove him to be possessed of culture and education in the very best sense of the words. The longer poem, which gives the name to the little book, is chiefly descriptive; and all through it the author shows an intense love of nature and an intimate acquaintance with natural objects. Many lines, descriptive of the varied way-side flowers are beautifully correct.

The publication was probably funded by a loan from the Sir Thomas White’s charity, sadly a copy of the book has yet to be found. In the 1880s, Robson and Barclay became socialists and supporters of William Morris. They founded the Leicester Branch of the Socialist League on Nov 1st 1885 and Robson was a frequent speaker on platforms at Russell Square and Humberstone Gate, where he specialized in giving lectures on the 'iron law of wages.' Robson also contributed to Tom Barclay’s Country and Midland Counties Advertiser.

Eventually Robson gave up his job and sold his collection of fossils so he could study to be a certified teacher. Barclay described him as a working man scientist and that he was a better writer than lecturer, since he did not always speak grammatically.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle 22nd July, 5th August 1876, 7th February 1885, 13th July 1889, Midland Naturalist 1 & 2, 1879 quoted in UK Beetle Recording, herbaria@home, The Wyvern, 16th July 1897, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

Deborah Ross (nee Goddard) born: Wymeswold 9th June 1828, died 10th January 1881 (Radical, Republican and Secularist)

George Ross, born, Leicester 14th April 1830, died in 11 Jan 1907 in Kempston, Bedfordshire (Radical, Republican and Secularist)

Many of the active woman suffragists in Leicester in the late C19th came from middle class backgrounds. Comfortable incomes and servants gave them time to indulge in philanthropy and charitable works. Deborah Ross' background was more humble and in consequence it makes what little we know of her more noteworthy.

Born Deborah Goddard, she was the daughter of a framework knitter who came to live on Wharf Street. In 1841, he had been a schoolmaster living at Frisby-on-the-Wreake, but, for reasons unknown, had moved into Leicester. Deborah must have been an independent spirit because at the age of 22, in 1851, she was living with a female lodger in George Street and working as a book keeper. In June that year, she married George Ross, a butcher and cattle dealer and they had a shop at 94 Wharf Street, where they lived. By 1871, they had six children living with them.

In 1864, George Ross was charged by Harriet Davis, a 22 year single woman, of Somerby, with non-payment of a bastardy order and was ordered to pay costs. One can only speculate as to whether her husband's infidelity had any effect on Deborah's outlook. Subsequent run ins with the authorities over defective scales and lack of licences for game suggest George might have been something of a risk taker.

However, at some time in their lives both Deborah and George became ardent Radicals and Secularists. In 1867, George became a committee member of the re-established Secular Society. At different times, in the period 1867-71, both Deborah and George were Secretary of the Society. In 1873, George bought five £5 shares in the newly formed Secular Hall Company. George was also elected as a Freemen's Deputy in the 1860s serving well into the 1880s. In the early 1870's George also became involved in the Republican movement which was campaigning against the proposed marriage grant to be given to the Duke of Edinbugh when the Queen already had an annual income of £385,000 from the public purse.

In 1872, Deborah collected the subscriptions from all parts of the town for the statue of John Biggs proposed for Welford place and in 1874, she is listed as one of the supporters of women's suffrage. From 1872, George was active in the short-lived local Republican Club. When the Leicester Liberal Association was formed in 1876, he became a committee member. This replaced the old United Liberal Registration Society.

Deborah was a supporter of Charles Bradlaugh and was the only woman reported to be among those on the platform with him at a meeting at the Temperance Hall in 1877. This was not a meeting on Secularism, but on the 'Relation of Population to Poverty.' It was held shortly after Bradlaugh and Annie Besant had been acquitted, on a technicality, of breaching the Obscene Publications Act. There crime was to have published a book on birth control and the case attracted widespread publicity. The press felt unable to print parts of Bradlaugh's speech in Leicester because 'Mr. Bradlaugh spoke in terms in rather too pointed a nature to be reported.' However, it did report him as asking why the death rate amongst the children of the poor, was three times that of the upper classes. He also advocated that the woman of the lower classes should have healthy surroundings and not be compelled to work when she ought not too. He wanted proper homes, that were not overcrowded and which had sufficient food for mothers to enable them to have healthy children. He presumable also advocated birth control. Clearly for Deborah, living of Wharf Street with six children, Bradlaugh and Besant had got to the heart of the matter.

Not all secularists had agreed with the stance taken by Bradlaugh and Besant and the leaders of Leicester Secular Society were among those who distanced themselves from Bradlaugh and subscribed instead to Holyoake's British Secular Union. However, George and Deborah Ross stayed with Bradlaugh and in 1878, George became secretary of the local branch of Bradlaugh's National Secular Society.

Deborah died aged 52, just a couple of months before the Secular Hall was opened. The cause of her death was diarrhoea, which was then Leicester's killer disease. Overflowing privies and pail closets in Leicester's slums were the root cause of this perennial epidemic. Her funeral was secular and conducted at Welford Road Cemetery by W.H. Holyoak. Mrs Harriett Law, Secularist lecturer and owner and editor of the Secularist Chronicle., who knew Deborah well, gave an address at her graveside.

Although George Ross became bankrupt in 1887, he managed to continue in business. When he died, he was buried alongside Deborah.

Sources: Leicester Journal, 26th April 1872, Midlands Free Press, 17th May 1873, Leicester Chronicle, 9th September 1876, 29th September 1877, 15th January 1881, Leicester Daily Post 2nd August 1873, Records of the Leicester Secular Society, F. J. Gould, The History Of The Leicester Secular Society, 1900, David Nash, Secularism, Art and Freedom, census returns

|

|

(Framework-Knitters Association, Hampden Clubs)

Thomas Rowlett was a prominent leader of the framework knitters from around 1812 onwards. He chaired meetings of framework-knitters representing both town and country districts. In 1812, the framework knitters of the town and county of Leicester, "as dutiful and loyal subjects of our venerable monarch," deprecated all violence - presumably the Luddites nad voiced concern that they were implicated..

In 1816, Thomas Rowlett, who had passed half a century in the hosiery trade, emerged as one of the radical leaders of the local Hampden Clubs. The club cost a 1d a week to subscribe to an its basic principles were that representation alone constituted political liberty, that the vote should be given to all those who paid taxes and that parliaments should be elected annually.

During the strike of 1817, a charge was brought against him for breach of the Combination Laws. In May 1824, he gave evidence to Parliamentary Committee on Artisans and Machinery which paved the way for the repeal of the Combination Laws.

In 1818, a resolution from the framework knitters stated that:

That we are unnecessarily deprived of the anticipated blessings of peace which we fondly hoped to enjoy: that comfort and contentment have been banished from our dwellings by misery, wretchedness and want; that however industrious and frugal, we must still be clothed in rags and endure the piercings of hunger; that instead of seeing our offspring vigorous and healthful, they are rendered a weak and puny race....

Sources: Leicester Journal 6th March 1812, Leicester Chronicle 28th February 1818, 8th May 1824, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954

|

|

Born: Leicester 1847, died Sunday October 30th 1892 (Women's Liberal Association)

Mary Royce qualified as Leicester’s first female doctor in 1890 at the age of 43. She had started her studies in 1879 and had combined them with running and financing a class for youths and men in Lower Church-gate which was in the midst of Leicester's worst slums.

Mary Royce was the daughter of Alderman George Royce, who carried on business as a currier (leather curing) in Belgrave-gate. Mary was sent to one of the best girls' private schools in Leicester, Belmont House in De Montfort Square, where she received a wide education, which included science and the classics.

In 1868, on the prompting of the minister at the Gallowtree Gate Congregational Chapel, (now the site of Boots) she began a Sunday School in rooms on Sanvey Gate. By 1875, her class was growing, not just in numbers but also in its age range and and had developed beyond the traditional Sunday school model. Mary had a good knowledge of chemistry and so began to teach science to her young men. The class took on social aspects when Mary arranged "pleasant Saturday evenings." when sketches, some written by Mary herself, were performed. She also arranged rambles and outings and later a discussion group was started. Mary was a strong advocate of the temperance movement and expelled anyone who transgressed.

Mary Royce was also an authoress of some repute: "Maud's Life Work," was published in London in 1873 in two volumes and was written under the nom de plume of Leslie White. One of her works, "Little Scrigget, or the Story of a Street Arab," went through several editions. This was followed by another tale of Leicester street life, entitled "The Prodigal Son." Both books were published in Leicester in 1875 by J.&T. Spencer and had religious themes. In the late 1870s, she decided to abandon her literary career and become a doctor.

In 1879, after her class has moved premises several times, she financed a new building in Lower Church Gate to be known as the Royce Institute. The rooms were maintained at her own expense and were open during the daytime for reading and recreation, and at week- nights and Sundays for instruction in various branches of knowledge. It also had a football team with the name 'Miss Royce's Class.' There nearly 100 members of the class and the Royce Institute formed a link with the Desford Industrial School for Semi-Delinquent Boys.

After passing her medical exams, Mary chose not to go into general practice. Instead she bought two cottages adjoining her Institute which she converted to a surgery where she could treat the poor. She usually charged one shilling for each visit, but often returned the money when the patients left. Although there were many who would not visit a woman doctor, there were more and more women who were pleased that they could see another woman for help and advice. It was not long before Mary Royce found herself treating not only the poor, but also richer patients in the 'better off' districts of Leicester.

Mary Royce had taken the middle class practice of charitable and philanthropic work among the 'poorer classes' to a different level. All accounts suggest she was unostentatious, quiet and preferred a simple and frugal life, albeit based at the very substantial Gotha House on Gotham Street. In 1886, she was a founding member of the Women's Liberal Association and was its treasurer. Her only recorded public statement was an address given at a meeting of the Association on 'tight-lacing,' (tight corsets were a health risk) 'self-control,' 'over-excitement,' 'temperance,' and kindred matters of health.'

In April 1892, Mary was persuaded to stand for election as Poor Law Guardian in St Margaret’s Ward by fellow members of the Women’s Liberal Association. She was elected unopposed and proved a conscientious member of the Board, attending every meeting. Sadly, her career was cut short in October 1892, when it was reported that she died after contracting erysipelas (St Anthony's fire) whilst visiting a patient in the infirmary of the "the sad house on the hill." (workhouse). Today deaths from this disease are rare.

A day or two after her visit Mary was seized with shivering attacks, but attributing them to a cold took no precautions. She lay unconscious for several days gradually losing strength and after a short lucid interval, she passed away aged 46. As a result of her death, Guardians were no longer permitted to visit the Workhouse or Cottage Homes during outbreaks of infectious diseases in the town. Mr Page-Hopps, the Unitarian minister officiated at her burial and the dead march was played in her honour at the Great Meeting.

Mary Royce's Institute on South Church-gate was demolished in May 1970 to make way for the ring road. Instead of moving the Institute to an outer council estate where the former residents of the area had been re-housed, a new building was created in Crane Street next to St Margarets Church. The Royce Institute carried on largely as a religious sect with a slowly dwindling congregation until 2020, when the trustees put the building up for sale.

The portrait of Mary Royce and other material is now at the Record Office of Leicester, Leicestershire & Rutland.

Sources: Leicester Daily Post 19th & 29th October, 1st November1892, Leicester Chronicle 23rd January, 31st October, 5th & 12th November 1892, 4th February 1893, 12th June 1970, 6th January 1978 (Bernard Elliott)

|

|

Born: 1754, died 1792

Charles Rozzell was a self-educated framework-knitter who became by turns a teacher, official spokesman for the framework-knitters, and bard of the local Revolution Club among other things. He wrote on many topics of local interest, from the Leicester Infirmary to local cricket matches, and he also produced a great deal of Whig propaganda at election times.

|

|

Died: 20th June 1961 (Labour Party)

Robert Russell was elected to the City Council for Abbey ward in 1945 and was Chair of Finance Committee 1956-60. He was also president of the City Labour Party 1949-50, a magistrate and a member of the National Health Executive Council for Leicester from its formation in 1948. He died in office.

|

|

Born: Thomastown, County Kilkenny, Ireland, 1921; died: June 1997 (Labour Party)

Martin Ryan worked in the Scottish coalfield before moving to Leicester in 1947. He worked in the Desford Colliery for 14 years before being elected as an official of the N.U.M. He later became president of the Leicestershire National Union of Mineworkers. He was chairman of the Leicester South Labour Party in the 1970s and was elected to the County Council in 1974. During the 1990s Martin was leader of the Labour Group on the County Council representing Spinney Hill and later Mowmacre ward. He was chair of the County Council in 1987. He died from a brain haemorrhage after being taken ill at a Labour Party meeting, just one month after he had given up his seat on the County Council.

Sources: Leicester Mercury June 1997, author’s personal knowledge

|

|

|

|

Back to Top |

|

© Ned Newitt Last revised: December 24, 2024.

|

|

|

Bl-Bz

Leicester's

Radical History

These are pages of articles on different topics.

Contact

|