Bl-Bz

|

|

| |

Died: February

2006, aged 79 (Labour Party)

Fred Blackwell worked as a senior

housing officer at Leicester City Council from 1973 until his retirement

in 1983. During this time, when the Labour Party was reluctant to engage

in street politics, he was a key figure in the broad campaigns against the

National Front. He was Chairman of the Inter-Racial Solidarity Campaign

and a committee member of Unity Against Racism. With Stewart Foster, he

became a City Councillor for Coleman ward. He died at

his home near Darlington from a cancer-related illness.

Source: author’s personal knowledge

|

|

Born:

Bradford 8th November 1952, died 13th May 2019 (Trades Council and Labour

Party)

Anne Blair was a National Union of

Teachers (now the National Education Union) activist and a member of the

executive committee of Leicester and District Trades Council with a

special interest in the issues of Equality. She supported every trade

union campaign in her own union and also on behalf of LDTUC. She compared

every Leicester May Day Rally in recent years, apart from 2019 when she

was becoming seriously ill.

Anne was very much an internationalist and was the international officer

for her union locally. She took a particular interest in Latin American

politics and was the secretary of the local group of the Cuba Solidarity

Campaign. She fought tirelessly for the release of the Cuban 5 from their

incarceration in the US (they were released in 2016) and against the US

economic blockade of Cuba. One of her last acts was to be in Liverpool

during April 2019 to see her union celebrating the sending of musical

instruments donated from all over England and Wales to Cuba by container

ship. Anne had coordinated the collection of instruments in and around

Leicester as well as other parts of the Midlands.

Anne was born in Bradford and her

maternal grandfather was a prominent I.L.P. member in that city and would

have been its mayor had he not died himself through cancer (which also

claimed Anne) before his proposed year of office. Anne made sure that he -

John William Flanagan - appeared in the book, Uncovering Resistance

published in 2015 about conscientious objection in World War I as he

refused to fight and kill fellow working-class men. Anne was a

long-standing Labour Party member, but left when her namesake Tony Blair

took Britain into conflicts in the Middle East. Upon Jeremy Corbyn’s

election as leader, Anne re-joined the party in Leicester West and

characteristically threw herself into activity. Up until only a few weeks

before her death, she was out canvassing for the local elections.

Anne came to Leicester in the early

1990’s to teach accounting and economics at Wyggeston and Queen Elizabeth

I College and taught right up to the end of term in April 2019.

Source: Tony Church

|

|

Born: Leicester, 1903, died Leicester 1949 (Communist Party,

Co-op Party, National Unemployed Workers' Movement)

Claude Boat was a leading activist in

Leicester's unemployed workers' movement during the 1930s. In January

1932, following a mass meeting and march of 1,000 people, he headed

a deputation of six to call on the Public Assistance Committee to refuse

to operate the hated means test. The N.U.W.M. wanted to reverse the cut in

unemployment benefit and wanted £1 per week for people over 18 years old,

15s for a wife and 5s. for each child. "Those are our demands. and they

are not more than is necessary to keep us morally and physically in a

proper condition." The Committee unanimously decided that this was a

matter for Ministry of Labour and not a matter for them. (Amos Sherriff

seconded the motion.) Whilst the Labour members were opposed to the means

test, they were not prepared to defy the law.

In July 1934, (although now in work) Claude became the

N.U.W.M. candidate in a local council bye-election. This foray into

electioneering was pursued nationally by the N.U.W.M. who tried

unsuccessfully to get Labour candidates to stand down in favour of

the unemployed. Claude told the press that

the unemployed were frustrated with the Council's failure to get slum

clearance underway. The Leicester Evening Mail reported one of his

meetings under the headline "Fiery Eloquence"

Mr C. H. Boat, the local National Union of Unemployed

Workers' Movement candidate for the Leicester City Council, addressed 16

meetings in the open air last night. At one street he had what punsters

would describe as a warm reception. He was on his portable platform when

immediately opposite him a fire broke out at a house. Nothing draws a

crowd like a fire engine, and when the excitement had subsided, which,

fortunately for the occupants of the house, was very soon, Mr. Boat reaped

the benefit of the lingering crowd.

Claude Boat got 96 votes, whilst his only opponent,

Labour's Sam Cooper got 1,186.

Whilst other organisations were represented on the

Council's Public Assistance Committee, the N.U.W.M. request for

representation was rejected. Boat continued to be involved with

delegations to meet with the P.A.C., urging free milk for children,

payment of trade union rates on work schemes and a fuel or coal allowance

for the unemployed.

By 1936, the leaders of the local unemployed were

increasingly involved in opposing the local Fascists and Claude

frequently chaired anti-fascist meetings in the Market Place. He was soon

involved with the Spanish Aid Committee and was also became active in the

Co-operative movement. Like R.V. Walton,

he left the Communist Party and joined the Co-op Party in the late 1930s. The 1939 register records him as being an (unemployed)

confectionary wholesaler.

Source: Leicester Evening Mail, 13th

January 1932, 30th October 1933, 13th, 16th June, 4th July & 12th December

1934, 12th February 1935, 12 February 1935, 3rd June 1939. Leicester

Mercury 20th February 1935, 12th July 1938 PAC minutes 12th January 1932

|

| |

Born:

12th Apr 1923, died March 1995 (Communist Party)

Norman Bordoli went to Gateway

School and during the war was a telegraph operator, serving on motor torpedo

boats. He was a knitter in the hosiery trade and became a member of the

National Executive of the Hosiery Union. He was chairman of the Eyres

Monsell Tenants Association during the 1960s and 1970s. He first stood as

a Communist Party candidate in 1968 and became branch secretary of the

Leicester Communist Party during the 1970s.

Source:

author’s personal knowledge

|

|

Born c.1882, West

Ham, Stratford (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

Walter Borrett worked as a compositor in

the print trade and a member of the Typographical Association. He

came to Leicester c1907 and became secretary of Westcotes I.L.P and then

served as

secretary of the Leicester I.L.P. from 1912 to 1914. He then became the

I.L.P. organiser for Leicester and Leicestershire from 1914. He kept in

close touch with Ramsay MacDonald keeping him informed of the position in

Leicester and in 1917, he wrote a short

monograph of George Banton.

During the war, he dealt with hundreds of cases of men previously rejected as

unfit for service. These men were called back for re-examination by the

Leicester Medical Board to try and send them into active service. He also

worked with tenants to ensure landlords did not extort high rents in

contravention of the Rents Restrictions Act. After the war, he became

manager of the Blackfriars Press and was on the staff of Leicester Pioneer

during the 1920s. In 1919 & 1920, he stood as a Labour candidate for

Westcotes & Castle wards.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 29th

October 1919 and 22nd October 1920

|

|

Born: 30th

January 1905, Cardiff, died: 30th April 1994 (Labour Party &

S.D.P.)

Bert Bowden came to Leicester in 1933

and worked for Charles Keene’s firm Kingstones. His job was to cycle around to collect hire purchase payments.

He was elected to the City Council for De Montfort ward in 1938. In 1941,

he joined the RAF and became a pilot officer in 1943. In the 1945

landslide election, he won Leicester South which had been a safe

Conservative

seat. The subsequent incorporation of the Saffron Lane estate had made the

constituency more winnable for Labour.

Early in 1947, Bowden became PPS to the Minister

of Pensions. By 1949, he had become a junior whip, making

his name first as deputy, then as chief whip for the Labour party during

its years in opposition. In Harold Wilson's first government in 1964, he

was made Leader of the House, although he was replaced by Richard Crossman

two years later. In 1966 he was appointed Commonwealth Secretary and paid

the first official visit of a British minister to the rebel Rhodesian

regime after U.D.I.

In March 1963 he said:

“I do

not like the idea (of televising parliament) ... I do not want Parliament

to become an alternative to That Was the Week That Was or Steptoe and Son

or Coronation Street.” Ironically when he

stood down as MP in 1967, he left politics to run ITV. He became a life

peer in January 1964 as Lord Aylestone and in the 1980s, he joined the SDP.

|

|

|

John Bowman

Born: ? died: ? (Chartist)

John Bowman was an active Chartist from 1839 onwards. He

was a member of the All Saints Chartists and was critical of Thomas

Cooper. He was also secretary of the Woolcombers' Protective society

|

There was opposition to this memorial to George Bown being

placed in Welford Road cemetery.

|

Born: Leicester 7th

February 1770, died: 8th April 1858, (Jacobin, Reformer &

Chartist)

George Bown’s father was a

pay-sergeant in the Leicestershire militia, who later had a business as a

carrier and surveyor of the turnpike roads. George

was born in

Leicester and was educated at a private school, first conducted by a Mr.

Garrick and then by a Mr. Field. His parents wanted him to become a

hosiery manufacturer, and consequently apprenticed him as a

framework-knitter. But he did not like the work, and abandoned it to take

up the study of medicine. After studying at Oxford and in one of the large

London hospitals, he came back to Leicester as the assistant of a Dr.

Peake, who was then considered one of the ablest practitioners and

surgeons in the Midland Counties. During this time

he often

attended upon a

regiment of dragoons stationed in the town. Once he had to supervise the

flogging of an offender who had been sentenced to 150 lashes with the

whip. Bown secretly advised the prisoner to cry out loudly before he

became too exhausted to utter a sound, assuring him that this would bring

about a cessation of the punishment. The soldier appears to have been too

brave a man to utter any token of his suffering, and the thrashing went

on. Bown, however, could not stand it, and long before the full penalty

had been paid he gave instruction that the victim could endure no more,

and the punishment must cease.

Bown then went to London in

search of medical work where he became acquainted with the satirist

Peter Pindar ( the

pseudonym of Dr John Wolcut). Pindar advised him to abandon medicine in

favour of political literature. This

change of profession brought him back to Leicester where he

became an assistant to

Richard Phillips in

his pamphlet room at the corner of Gallowtree Gate and

Humberstone Gate. Phillips was a teacher of

mathematics, sciences and a bookseller who founded the

Leicester Herald in 1792.

Bown became the secretary of the Constitutional

Society for Promoting Equal Representation of the People in Parliament

and in December 1792 it published a manifesto. This laid out the principle that

all

civil and political authority is derived from the people

and advocated:

the right of

private judgement, liberty of conscience, trial by jury, freedom of the press,

the freedom of elections, equality of rights, the inviolability of private

property.

This statement of principle offered

whole hearted support for the constitution and claimed

that the Society deplored the abuses and corruption

that have gradually crept into it and wish to reform because we wish to preserve

it.

The following week the county gentry

with the still familiar names of Winstanley, Pochin, Babington, Skeffington,

Packe, Meynell and Herrick published their own statement of principle in which

they resolved to use their "utmost endeavours to discover the authors

publishers and distributors of all seditious writings in the county of Leicester

particularly and all persons engaged in any illegal conspiracies for the

publication and the distribution of such writings for the exciting tumult and

riot" and enforce the law strictly against them.

The following month,

Richard Phillips was imprisoned for selling Tom Paines’s

Rights

of Man. Although

Phillips managed to edit his paper from prison, Bown played a

key role in

keeping the Leicester Herald going.

In May 1794 Bown was briefly arrested for his Jacobin sympathies,

although some obituaries say Bown was also imprisoned for selling the Rights of

Man. Following the destruction of Phillips' shop in a fire in 1795,

Bown moved to Nottingham

where he was successively a

hatter and hosier, and a clerk in the works of Sir Richard Arkwright. Then

he started in business at Loughborough.

In 1804, he

married Miss Gardiner (the sister of William Gardiner, the musical

celebrity), working for a time as a hatter and then running a

school in Loughborough. He returned to Leicester in 1811 as the second editor of

the Leicester Chronicle.

The Chronicle's main rival was the Tory

Leicester Journal which was edited by John Price. The Journal

specialised in the 'coarse and ribald abuse' of its opponents with no

regard for the truth and Bown was employed to counter Price's hyperbole. During Bown's

editorship the war of words between the Chronicle and the Journal

developed to almost libellous proportions. Unfortunately

the invective in Bown's articles also gave offence to the Chronicle's

supporters who claimed it 'violated the canons of decency' and that they could not lay a paper on their table

for fear their wives and daughters might read it.

Bown was replaced as editor from 17th April 1813 by Thomas

Thompson who pledged to cease the 'illiberal wordy warfare' with the

Journal. (this was not reciprocated) Bown and his wife thereafter

became agents for the sale of lottery tickets.

In 1821 Bown opened a school on

Charles Street which for unknown reasons was

'broken up and dispersed, by an extraordinary instance of persecution.'

It is not clear what happened, but Bown was imprisoned only to reopen the

school in 1822. He advertised spaces for 24 pupils and 8 girls whilst his

15 year old daughter Emily ran an under fives class. The school was not a

success and the reason for this may be a consequence of Bown's stance on

religion. Following Bown's death, one correspondent refers to her brother being withdrawn from the

school in consequence of Bown's repudiation of the Bible.

Bown then found employment as the book keeper to the

‘Hope’ coach at the Bell Hotel.

In 1830 Bown authored the Animadversions on the

recent conduct of H.J. Wilkinson, soi disant editor and proprietor of the

Leicester Herald. which was published by

A. Cockshaw. Wilkinson had

recently got into financial difficulty and Bown was not doubt taking

revenge on another Tory newspaper.

Following the passing of the

Reform Bill in 1831, Bown became clerk to the Reform Society which was at

the heart of the Radical-Whig alliance. After

this alliance had taken control of the Council, Bown was appointed as

the Council's Accountant in 1837. The Leicester Journal fulminated that in

appointing this producer of scurrilous hand-bills, Liberalism and Atheism

had been rewarded. Bown replied that:

I have for nearly 47 years been labouring to deserve

and obtain the maledictions of the despicable faction of which these

co-journalists are the organs. I feel their long silence as reproach that

I have been indolent.

From the mid 1830's, Bown had worked as a teacher at the

Mechanics' Institute teaching astronomy, geography and grammar. In August

1838, an advert appeared in the Leicester Chronicle over Bown's

name stating stated that certain classes at the Mechanics Institute had

been suspended. "..against whom the doors of the Class Rooms have, on

some frivolous, and despotic pretence, been lately locked, would now

restart in the Commercial Rooms, It is proper to announce that these

Classes will not be subject to ... arbitrary control inquisitorial

inspection."

It would seemed that the Mechanics Institute suspended

his classes after he was alleged to have criticised the Bible.

He either was sacked or resigned. It was in this way that Bown's classes

restarted in the Commercial Rooms which was also the Owenite Social Institution.

W.H. Holyoake recalled that:

“I met with kindred spirits at

Barlow’s rooms at the top of the Market Place. The meetings were attended

by some young fellows who had left the Mechanics Institute ....... At

this time Robert Owens's views were being discussed all over the country.

We young men were much influenced by that remarkable man George Bown, an

old Jacobin and radical. On Sunday mornings we went to Barlow’s rooms to

read Owen's New Moral World and other periodicals.”

In 1840, Bown became the

Council’s Inspector of Nuisances at an annual salary of £20. Some

thought the post was

a sinecure, but Bown used it to advance ideas of public health. He pointed out that:

No fact in physical science stands on a more

indisputable basis than that stagnant water containing animal and

vegetable matter in state of decomposition is the great source of the

various grades of what is termed typhus fever from its mildest to its most

malignant form.

He began to survey all the public

health nuisances in Leicester and it was his idea that the Council should

appoint Medical Officers of Health. From 1846, Mr Buck assisted him in a

medical capacity. As a result, Leicester became the first British local

authority to have medical officers. As a wave of cholera approached

Britain from the continent, he urged the council to take precautions:

"Every death

that may ensue from any neglect of preventive means is in fact at least a

moral manslaughter...."

In the early 1840’s Bown became

the First editor of the Leicester Chartist paper the Midland Counties

Illuminator. Shortly before Bown’s death Thomas Cooper described him as a

“fine intellectual old man, whose pamphlets, fly-sheets and

contributions to periodicals would fill many volumes if collected.”

However, in 1842 Cooper accused him of deserting his Chartist principle in

order to ‘get a place.’ (with the Council) At the time George Bown was also

participating in Cooper's

bête noir, the Complete Suffrage Association

where he presented a paper asking whether governments were justified in retaining

overseas territories which they had obtained by force. Bown's response to

Cooper (who had just been arrested) was:

I can pity the fate of Cooper, but

my deepest commiseration is extended, in the spirit of unfeigned

charity, to the fellow who, having hawked his wares over both

continents, fancies he has reached the climax of his fame and glory with

being the ignoble tool of Athanasian (high church) parsons and the Tory

Lumpkins of a bigoted Squirearchy.

Bown’s commitment to

Chartism lasted longer than Cooper’s. In 1848, he published a pamphlet on

Physical Force: An Address To All Classes Of Reformers, But Especially

To Those Who Are Unjustly Excluded From The Franchise in which he

rather long-windedly declared physical force should be held in reserve, as

a threat to obtain the vote, behind moral force, but nevertheless advised

workers to ‘get arms.’ This caused some dismay amongst

his middle-class radical friends.

Bown resigned from his Council position

in 1849 aged 79 and he then went to live at the Trinity Hospital. Whilst

there, he boycotted the sermons which the inmates and benefactors

were required to attend. In 1857, aged 87 he spoke at the demonstration

following the defeat of Sir Joshua Walmsley saying he had ever

advocated the right of man to suffrage independent of the number of bricks

he might have over his head, the number of panes of glass in his house or

the amount of money in his pocket.

Bown remained a freethinker until his

death and it is possible that, like Paine, he was a Deist, opposing

organized religion on the grounds that nature and reason provided the

necessary means to experience God. One of his critics wrote:

...did any man in Leicester do more to disseminate

the principles of infidelity amongst a class of young men over whom his

position, in times gone by, gave him a powerful influence?. Mr Bown

himself was never ashamed of this. Indeed, his whole life, ..... was one

of continued protest against the fundamental truths of Christianity.

After his death, the Leicester

Chronicle was described as indulging in the "Pursuit of George Bown into

his Grave" after it published numerous letters attacking Bown and the

proposed monument. James Plant wrote to defend the memorial saying:

is not to be erected to the late George Bown

for his "Ultra-Republicanism," or for his admiration of that somewhat

fossilized production, the 'Age of Reason," or to his violent temper, and

at times intemperate language: - let the grave close over these defects.

No it is intended as a mark of esteem for his faithful adherence, in

perilous times, to the cause of civil and religious liberty; and to the

great Protestant principle of the right of private judgment. No flattery

could win, threat intimidate, or reward buy off, his firm adhesion to

these great principles, through a long and stormy life.

Bown was buried in Welford Road

cemetery and his funeral was well attended by civic leaders. His grave is

marked by an nine foot high sandstone obelisk. The inscription reads:

"Here lies one who never feared the face of man."

Sources: Leicester Journal 21st &

28th December 1792, Derby Mercury, 29th

May 1794, Leicester Chronicle, 6th February 17th April 1813, 26th October

1822, 17th September 1842,

8th May 1858, 3rd November 1860, Leicester Guardian

24th June 1857, Leicester

Journal 24th January 1840, Leicestershire Mercury, 18th

March 1837, 10th

October 1840, 26th August 1848, South Midlands Free Press, 17th

April, 15th May 1858, Leicester Reasoner, 1902, Leicester Daily Post,

23rd, 24th November & 3rd December 1917, A. Temple Patterson, Radical

Leicester, Census returns

|

|

Born: 1926, died:

2002 (Labour Party & S.D.P.)

Tom Bradley was a Gaitskellite and

a founder member of the Campaign for Democratic Socialism. This was set up

in 1960 to fight against leftwing proposals for more nationalisation and

for unilateral disarmament.

Having joined the Labour party

when he was 15, he immediately began climbing the party and union ladders,

especially the latter. In 1946, he became a branch officer of the TSSA. By

the age of 32 he was on its executive committee and three years later its

treasurer, under the belligerent rightwing president, Ray Gunter. He

perfected his public speaking skills by contesting hopeless parliamentary

seats: Rutland and Stamford (1950, 1951, 1955) and Preston South (1959).

He did better in local government, winning a seat on Northamptonshire

county council aged 26 and Kettering borough council five years later.

He

made his first entry into Labour's factional politics in 1962 when the

leftish Sir Lynn Ungoed-Thomas retired from Leicester North East to become

a high court judge. As the candidate of the moderate right, Bradley won

selection over Russell Kerr, an Australian left-winger backed by CND. In

the following election, he

increased Labour's majority.

After his November 1962 maiden

speech on the ‘clerical slums’ in which railway clerks worked, Bradley

almost disappeared from parliamentary sight. He saw himself as a

trade unionist MP, devoting most time to the union and less time to his

constituency. His situation changed after the 1964 election, when Ray

Gunter became minister of labour and Bradley took his place as president

of the very moderate white-collar union, the Transport Salaried Staffs'

Association (TSSA). When Gunter declined to stand again for Labour's NEC,

Bradley replaced him there.

His only parliamentary post was as

parliamentary private secretary to Roy Jenkins, increasingly his mentor.

Although he considered himself a ‘binder-together’ and

a ‘middle-of-the-road man,’ he was one of the 68 Labour MPs who had rebelled against a three-line whip

in 1971 to vote with Ted Heath's Tories to join the Common Market.

Ten years later he followed Roy Jenkins into the Social

Democratic party when it defected from Labour in 1981. This effectively

ended his political and trade union career. In the 1983 general

election he finished third behind the Tory and Labour candidates in a seat

that he had held since 1962. With ex-Labour councillor Shah also standing

as an independent, it is remarkable that Patricia Hewitt only lost by 933

votes to the Conservative Peter Bruinvels.

Sources: The Guardian

|

| |

Born: Leicester, September 1927, died 2002

Roy

Bradshaw was an engineering worker who joined the Communist Party during

the Second World War. He stood as a City Council candidate for Charnwood

ward in 1963 and probably in other elections too. During the 1970s, he was

a familiar figure in town as a seller of the Morning Star and Soviet

Weekly.

|

| |

William Bradshaw was secretary of the

Leicester Unemployed Broad Committee in 1934 and a member of the N.U.W.M.

He was a Communist Party candidate in local elections and was still a

party member in the 1970s..

|

| |

Born Westminster

or Shoreditch June 1803, died: Leicester 12th March 1846

(Chartist poet)

All men are equal in His sight,-

The bond, the free, the black, the white,-

He made them all,- and freedom gave-

He made the man,- Man made the Slave!

John Henry Bramwich was one of a

group of Chartist poets who were working men. After being apprenticed at

the age of nine, he enlisted in the army at the age of 17 in 1820 and spent sixteen

years as a private. He spent ten years in the West Indies where his

daughter was born. Tiring of the army, he returned to Leicester to work as

a framework knitter. He was best known for his hymns, Britannia’s Sons,

Though Slaves Ye Be and Great God, is this the Patriot’s Doom?

The latter was composed for the funeral of Holberry the Sheffield Chartist

who died in York gaol. He also contributed to Cooper’s Extinguisher

(1841) and 14 hymns to the Shakespearean Chartist Hymn Book. Along

with fellow poet William Jones, he assisted Thomas Cooper at his adult

Sunday school. Thomas Cooper wrote his obituary in the Northern Star, (4th

April 1846) and included a moving letter written by Bramwich as he lay

dying slowly of consumption:

“You know, a lungless slave is good for

nothing now-a-days in the British slave-market. I can assure you, it

requires Samsons and Goliaths to work the stocking-frames

they are making at this time. I look upon myself as a system murdered

man.”

Shortly before his death his family

were converted to Mormonism. He

composed a hymn for his own funeral and

was buried in a pauper’s grave at St Martin's Church. (now the Cathedral).

William Jones also composed a hymn in his honour that was sung at a

meeting held in the Market Place to commemorate him. His wife and family

then emigrated to the United States where some of his descendents are

still Mormons.

Sources: The Northern Star, 2nd

July 1842, 4th & 16th April 1846, Thomas Cooper,

The Life of Thomas Cooper, 1872

|

| |

Born Louth,

Lincolnshire, c1852, died 1936 (Secularist & Socialist poet)

Alfred Brant was a compositor by

trade. During the 1890’s, he contributed articles to the Wyvern on a range

of topics including ‘White Slaves in Leicester,’ and a description of 1897

May Day demonstration. Under the acronym ‘A.C.B.,’ he wrote an

autobiographical poem which tells of the reader of his secularism,

socialism and his joy at working at the Leicester Co-operative Printing

Society. In 1910, the Co-operative Printing Press published ‘A

Rhymster’s Recollections,’ a 32 page collection of his writings,

containing a sonnet in dedication to Ramsay MacDonald and a poem welcoming

delegates to the 1911 Labour Party conference in Leicester. He was a

secularist, a member of F.J. Gould’s ethical guild and a superintendent of

the Secular Sunday School.

He later worked in the composing room of the

Leicester Daily Post and for a short time edited the satirical paper

Jackdaw and some of his poems were published in the Leicester

Mercury. He published A Leicestriad of Civic Pride in 1928 and

in 1936 he died a week after being hit by a car whilst crossing Narborough

Road - he was 82.

Sources: Leicester Co-operative

Record, October 1910, The Wyvern. Leicester Mercury 26th & 29th February

1936

|

| |

Died 1926 or 1927 (Liberal)

J. H. Brewin was the manager of Glenfield Progress

Co-operative Boot & Shoe works from its foundation in July 1892 until his

retirement in 1926. He was also the chairman of its committee.

Sources: Leicester:

A Souvenir of the 47th Co-operative Congress, Manchester

1915. Leicester Co-operative Magazine, January 1927

|

|

Born: Great

Yarmouth, 1st January 1898, died: 28th October 1975

(Labour)

Sid

Bridges was the son of a Norfolk blacksmith. He left home at the age of 13

eventually working in Lincoln for a firm of steam engineers. He went to

France, during World War One, as a machine gunner and was wounded in the

eye and knee by shrapnel during the Battle of the Somme. After the war he

returned to Lincoln, but was frequently out of a job. He worked on and off

for five years with a circus, looking after the lighting and doing other

jobs. He came to Leicester, with his wife and baby, in 1929, but was still

dogged by unemployment. He eventually joined the maintenance department of

Leicester Co-op in 1933 and worked there until he retired in 1966. He

joined the Labour Party in 1919 and he became chair of TGWU 5/249

Leicester Branch from 1933-1970. He was president of the Trades Council in

1946.

In 1945, he was elected to the

City Council for Latimer Ward and was chair of the Transport Committee for

21 years. He was credited with pulling Leicester City Transport out of the

red, turning it into a paying concern with some of the lowest fares in the

country. He had responsibility for the replacement of trams with busses.

In 1964, he urged the Council to stop any dealings with Everards brewery

whilst a colour bar was operated at the Admiral Nelson pub in Humberstone

gate. That year he had been made an alderman, becoming Lord Mayor in 1965 and

he was awarded

freedom of the City in 1971. The following year, with Labour back in

control, he become deputy leader of the council and with other members of

Labour’s ‘old guard’ was associated with the publicity designed to

discourage Ugandan refugees from coming to Leicester.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, 23rd

November 1964, 15th

May 1970, 29th October 1975, Valerie Marett, Immigrants

Settling in the City, 1987, Leicester City Council, Roll of Lord

Mayors 1928-2000

|

| |

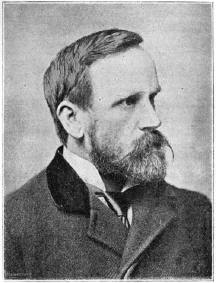

Born: 13th

April 1840, Littlemore, died: 1911 (Liberal)

Following the resignation of both

the local liberal MP’s in 1894, the Liberal party adopted Henry Broadhurst

(a working man) to placate the considerable number of working men voters

who had not been satisfied with the previous MPs. Henry Broadhurst had started

work at the age of twelve and then became a stonemason. He was involved

with repairing and enlarging churches and university colleges in Oxford

and later with the rebuilding of the House of Commons in the 1850s. He was

active in the struggle for universal suffrage and took part in several

demonstrations and meetings in the build up to the passing of the 1867

Reform Act. In 1872 he took part in the campaign to reduce the working

week and an increase in the hourly wage paid in the building industry. Broadhurst soon emerged as one of the leaders of the stonemasons

eventually giving up his work as a stonemason to become a full-time union

official.

In the 1880 General Election

Broadhurst was elected as Liberal MP for Stoke-upon-Trent and he became

one of the Lib-Lab supporters of Gladstone's government. In the House of

Commons He led the campaign for a government commission to investigate

working-class housing. In the 1885 General Election Broadhurst was elected

for the Bordesley seat in Birmingham and became an Under-Secretary at the

Home Office. He thus became the first working man to become a government

minister. However, his loyal support of the Liberal government upset some

trade union leaders and when he argued against the eight-hour day, Keir

Hardie remarked that he was more Liberal than Labour.

In 1890, the TUC supported Hardie

against Broadhurst by passing a resolution in favour of the eight-hour

day. Broadhurst was especially hurt when he discovered that his union had

voted against him. In the 1892 general election Broadhurst was defeated at

West Nottingham. His objection to the eight-hour day had lost him the

support of local workers and this enabled a local colliery owner to defeat

him. Attempts to be elected in Grimsey in 1893 ended in failure, but Broadhurst eventually won at Leicester in 1894. He held the seat until his

retirement before the 1906 General Election.

Sources: Bill Lancaster,

Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

| |

Died: 1902 aged

78 (Co-operator)

A bricklayer by trade, William

Brown became the first president of the Leicester Co-operative Society in

1863. He was architect, builder and workman, on a voluntary basis, for the

Society in its early days. He resigned in 1870, on his appointment as

storekeeper at No. 6 branch.

|

|

Born: Gumley, Leics, November 1812,

died: Germantown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 28th April 1887 (Chartist leader,

trade union leader)

George

Buckby was a framework knitter who was active in the 1840s in establishing

a consolidated union of framework knitters. From 1844, he campaigned

against the evils of frame rents and after 1846, he was one of the Chartist leaders

who attempted to revive the movement following the

imprisonment of Thomas Cooper. By the mid 1850s, he was actively agitating

against both the high price of bread and the adulteration of food. He

formed the Anti Dear

Food Association in 1856. He also gave his support to the Sunday League.

He was one of Leicester's most effective working class leaders and

was despised by the Whigs and Tories.

In May 1844, George Buckby, along with five others, was

sentenced to one month's hard labour. Their crime was one of intimidation:

'by hissing and groaning to intimidate and prevent Mr. Cummins' workmen

from working.' This followed some 600-700 people gathering in front

William Cummins' shop during a strike. The cause and nature of the

strike is not recorded, but in 1844,

William Chawner

brought a

test case against his employer Cummings, claiming that sums deducted for

frame rent had been illegally withheld and was a violation of the Truck

Act of 1831.

A verdict in favour of Chawner was

given at the Leicester Assizes, but was reversed on appeal to the Queen’s

Bench in 1846. It was the failure of this action which led the

framework knitters to seek legislation to regulate frame rents. Buckby was soon the principle spokesman of the

Leicester framework knitters.

In 1847, Buckby was described as having

assumed the position previously held by Thomas Cooper. Buckby having

initially opposed the radical candidates

Walmsley

and Gardner, was one of several Chartist leaders to sign a handbill

urging the working classes to support them. This was one of the first

signs of a rapprochement between the working class Chartists and the

middle class radicals. Key to this was Walmsley's and Gardner's initial support

for the abolition of frame rents.

In 1848, when the Chartism was once again

in the ascendant, Buckby was the Leicester delegate to the

National Convention. His departure for London was made the occasion of a

demonstration of over 7,000 Leicester Chartists behind a banner which

proclaimed that there were 42,884 local signatures on the petition which

was to be presented to Parliament.

J.F.C Harrison says that Buckby

supported

Joseph Warner who succeeded to form the

more militant physical force Working-Men’s

Chartist Association, whilst Buckby may have been sympathetic, he was also

very conscious of the need to avoid arrest and imprisonment. He looked

favourably on Ernest Jones' ideas and chaired a meeting addressed by Jones

shortly before Jones was arrested and imprisoned in solitary confinement. In the summer of 1848,

when Chartist meetings were

prohibited by the magistrates, he adopted the pretext of holding religious

meetings on a Sunday giving a sermon on a text from the scriptures. Police

still dispersed the meeting.

During the early 1850s, as

secretary of the framework knitters, Buckby led agitation against

the frame rents. He also petitioned parliament for their

abolition and for legislation to give knitters protection against

employers’ frauds. He was a keen advocate of workers’ co-operative

production. He kept up his support for Chartism at meetings of

the non-electors and was regarded as the 'great gun' of working class

speakers:

he thought that nine-tenths of the non-electors now

believed they had just a right to the vote as the highest personage in the

realm, so long as they paid their fair share of taxation. Yet for this

they were called anarchists and revolutionists: but he would remind them

that those epithets were applied to the men who carried West Indian

Emancipation, to the men who carried the Reform Bill, by those who were

fond of rotten boroughs, and by the men who loved Protection and dear

bread, to the Anti-Corn-Law-Leaguers (hear, hear). And now it was applied

to those who wanted to extend the Suffrage. He took part the election of

'47 as a non-elector, and in that of '52 as an elector; yet had his

intelligence increased so much in those few years, as to make this

difference in qualification? No, but during that time the non-electors, by

being his customers, had enabled him to keep a house of £10 and payments.

And so he became duly qualified elector; and so the non-electors, by

supporting the electors, enabled them to have votes, while they

themselves were excluded.. (1852)

In 1853, Buckby gave his support to the two victorious

radical candidates, Walmsley

and Gardner and when a great procession was

held to mark the event and the visit of the Hungarian reformer Lajos

Kossuth, the Chartists were well represented. Streets were decorated with

green and from George Buckby's window a banner hung across Wharf Street

inscribed "National education and Universal Suffrage."

Buckby still remained critical of the Liberal Party and in particular its

support for the Poor Law. He opposed the separation of men from their

wives and families at the 'Bastille.' He claimed that there was

hardly a day passed when a child was not found dead in bed in the

workhouse. In 1853, Buckby and

Joseph

Elliott, as secretary and chair of the Framework Knitters

Committee, lent their support to a bill which would prevent employers

making unjustified stoppages from wages paid. Buckby was consistently

attacked in the Leicester Chronicle and Journal as an agitator and one who

used violent language and claimed he and his close collaborator, Joseph

Elliott, had been paid 30/- a week.

Following the defeat of Sir Henry Halford’s bill on

frame rents, Barkby and Elliot threw themselves into a campaign to reduce

the price of bread. This was triggered by a slump in the hosiery trade

which had put many out of work. Buckby and Elliot organised meetings and petitioned the mayor on

the issue. Traditionally bakers sold a "quartern" loaf which ought to have

weighed four pounds. Buckby argued that some bakers carried on their

business in direct 'violation and impunity' to the law selling bread 4-8oz

lighter than it should be. He also drew attention to the millers who

adulterated flour by adding alum. The anti Dear Provision Association

successfully petitioned the Council to reinstate

the public servant who had checked weights and measures. The campaign also

held meetings for women only. (see

Mrs Woodford). They also

took the campaign to Hinckley where they were joined by

John Sketchley.

At this time, Buckby stood with those

opposed to closing pubs on Sunday. He opposed the "perpetual

meddling of the Sabbatarians who so recklessly attempt to deprive the

working classes of their just rights and privileges." At a

meeting in the Pasture, he told the crowd:

The " black slugs preached to them that they would

have a house above, not made with hands; but what they wanted, and what

they had a right to have, was a house below to live in. It was said the

curse of God would rest upon them for being discontented, and for meeting

on a Sunday to state their grievances. He (George Buckby) did not care for

the curse of God; there was a much greater curse than that to fear - the

curse of oppression and tyranny. While the people were starving, the

parsons and those who had wrung the money out of the sweat of the working

men, stood calmly by, and did not offer any assistance. (1855)

With Joseph Elliott, he convened a meeting

in 1856 to condemn the Council for refusing to allow a band to play on

Sunday afternoons on the racecourse. (Victoria Park).

Both Buckby and Elliott were treated as a ‘demagogues and disturbers.’ They were

victimised by middle-men and manufacturers and late in 1856, they took refuge

in emigration to the United States and where they settled in Germantown,

Philadelphia and Buckby found work as a fancy goods weaver. Because of the

local hosiery industry, quite a number of Leicester people settled in the town

and a least one man

from Leicester was killed fighting in the Federal army during the Civil

War.

In 1866, Thomas

Cook paid Buckby a visit whilst he was travelling in the United

States and found him living in a neat little house of five rooms, but had

not involved himself with trade unions or politics. It is interesting to note that in 1871, this one time opponent of

co-operation with the middle classes led a committee with Joseph Elliott which sent £24 from

Germantown towards the cost of John Biggs' statue. Three years later, in

1874, frame-rents were finally outlawed.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle, 18th May 1844,

6th March & 18th December 1852, 22 April 1854, 24 November 1855, 8th December 1855, 24th

Feb 1866, Leicestershire Mercury, 31st

July 1847, 10th, 17th

June 1848 22nd July 1848, 8th December 1855, 5th July 1856,

Leicester Guardian 24th February 1866, Leicester Journal,

30th July 1847,

14th December 1855,

22nd February 1856,

15th September 1871.A.

Temple Patterson,

Radical Leicester,

Leicester 1954, J.F.C. Harrison, Chartism in Leicester in Asa Briggs

Chartist Studies,

|

| |

Born Wood Green, 20th January 1892, died 1961 (I.L.P. and

Labour Party)

Clement Bundock said that he owed his education entirely

to Council schools and to his love of reading. He set out to become a

journalist and joined the staff of the Christian Commonwealth.

He was greatly influenced by

A. Fenner Brockway, and 1911 he went to

Manchester as sub-editor of the

I.L.P.'s national paper, the Labour Leader. Here, he began the work

as an I.L.P. propagandist and spoke for the I.L.P. at public meetings all

over the country. In 1916, he was a contributor to "Why I Am A

Conscientious Objector: Being Answer to the Tribunal Catechism" with

Walter Ayles, A. Fenner Brockway, A. Barratt Brown.

By 1919, he was editor of

Leicester Pioneer and manager of the Blackfriars Press. From Easter

1920, to Easter, 1922, he was the Midlands representative on the National

Council of the 1.L.P.

According to Len

Hollis, he was criticised for his outspoken editorial condemning police

brutality during the Rupert Street demonstration by the unemployed in

1921. He was President of the Leicester Labour

Party in 1922. In 1923, he was the Labour candidate for the Bosworth Division

coming second in the poll in a three-cornered fight.

That year,

he was involved with a local No More War demonstration.

During the General Strike, in May

1926, he attempted to get the TUC’s paper the British Worker

printed in Leicester, but was blocked by his union the Typographical

Association. The union said that the workers at the press should be on

strike and not at work even if it was producing a TUC newspaper.

By the 1930's, he had become the

national organiser of the National Union of Journalists and had left

Leicester. He was

author of The National

Union Of Journalists: A Jubilee History 1907-1957

and

The Story Of The National Union Of Printing, Bookbinding And Paper

Workers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959

Sources: Gloucester Citizen, 2nd March 1923

|

| |

Born: Banbury Oxfordshire, December

1855 (Socialist League, Secularist and Co-operator)

Max Bunton's father William Bunton

(1823-1893) was a leader of the co-operative movement in Banbury and a

bookseller and newsagent. He was an Owenite and Chartist, who

suffered imprisonment in the days of the chartist agitation. He named his son after the secularist G.J. Holyoake

and published the “Banbury Co-operative Tracts” together

with John Butcher.

In 1875, Maximilian was a clerk at

the co-op store in Banbury and in 1877 married Matilda Wyman in Leicester.

Around 1878, Max became the secretary of the Midland Federal Co-operative

Corn Mill Society in Ash Street which was owned jointly by several

co-operative societies. John Butcher, had proposed building the mill

and Max's appointment does have the air of nepotism about it.

Max became prominent in the local

co-operative movement and contributed articles

to the Leicester Co-operative Record with

titles like 'Work. or why do men starve.’ He

also became secretary of the Secular

Society and was a regular lecturer at meetings at the Secular Hall on

subjects such as 'Heresy and Persecution,' 'Garibaldi' or

'Charles Darwin.'

Max was also secretary of the local

Socialist League branch and as a result was responsible for bringing

several Socialist League members to speak at the Secular Hall. He

disagreed with the League's position on the co-op movement, in his view,

“Wealth, position, class

distinction, blue blood and favouritism, would soon be removed from their

present holders if Co-operation was more fully carried out.”

In a letter to John Mahon (secretary

of the Socialist League) he said that he found the

word revolution, contained in the League’s manifesto a “great stumbling

block to us in the provinces.” He also corresponded

with Edward Aveling. (Karl Marx’s son-in-law) Bunton was also

active in the Liberal Party and in the anti-vaccination agitation.

In December 1887, the Federal Co-operative Corn Mill went into voluntary

liquidation. Although mill had been financed by a number of different

co-operative societies, their reluctance to buy its flour meant the mill had

been struggling for some time. However in the reports given to its

co-operative backers, the failure was blamed on bad management and auditing.

It is possible that Corn Mill's financial crash had rendered Max's position as a rising star in local co-operative

movement as untenable. Drastic steps were required and in 1887,

Max Bunton

changed his name to John W. Gazey and then he and his wife emigrated to

the United States. The Corn Mill's debts were born by its

shareholders and was taken over and run by the Leicester Co-operative

Society.

Max, now John, found a job in Brooklyn working as a

bookkeeper where his services were 'greatly sought after, because of

his training received in the bankruptcy office of the English Government.'

In 1908 moved to Roselle Park, Union County, New Jersey.

There he worked as the borough's auditor for five years and was Justice of

the Peace of Union County for 17 years.

Max/John was mainly responsible in

securing a valuable piece of ground in the centre of the town to build the

Borough Hall. Judge Gazey also helped established a free public library

and kept it in operation for two years before it was offered to the

Borough Council.

He bought the house he lived in and set out trees, vines and fruit bushes

and gained notoriety as an expert in the cultivation of fruit.

Sources: Oxford Journal, 13th

October 1877, Leicester Co-operative

Record, December 1883, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and

Socialism, Leicester Chronicle,

2 February 1884, International Institute

of Social History (IISH): Socialist League (UK) Archives, Banbury Advertiser 10th

November 1927

|

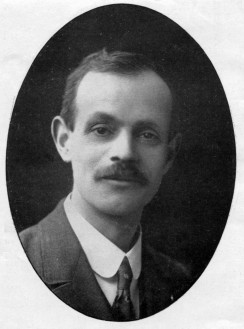

Willam Burden's grave in Welford Road cemetery

(uE 32) |

Born c1811, died 17th May 1853 (Chartist leader, Allotmenter and Owenite)

William Burden

was was described as 'one of the leading Chartists in this town, and

one of the most intelligent and judicious, though, at the same time, one

of the most firm of their number. He lately resided Nottingham, and we

believe he was a Secretary the Chartist Association there.' (1841)

Burden was a self educated framework

knitter, warp hand and overlocker. He had attended the Owenite Social Institution

and this led him to being accused of being a 'Socialist who burnt bibles.' He

described his accusers as:

Men who never seriously think, but

are always ready to believe; men whose disrelish for intellectual

improvement has made them scarcely able to discriminate between a comma

and a comet; and in whose hands to witness a book containing information

would as great a novelty, as to hear parrot parse sentence of grammar; men

who bawl mightily their unbounded veneration for the Bible, but think

nothing of violating its most vital injunctions continually; men who

adhere more strictly to the contents of a barrel, than the contents of the

Bible.

In 1840 he argued that Chartists

should; 'not support any government conducted on Whig, Tory, or any

other principle, that refuses to concede....Universal suffrage.'

Burden was consequently critical of the alliance

between 'aristocracy and democracy,' when the Leicester Chartists, Cooper,

Markham and Swain gave their support to the Tory candidate in the 1841

Nottingham election.

Rejecting John Bigg's call for Household Suffrage, he argued

for the

People's Charter saying that:

"while property and not person is the qualification

to vote for Representatives Parliament, wealth will always find means to

exercise undue influence, and the creators of that wealth be prevented

from occupying their justly entitled position."

Though he shared Cooper's view that the repeal of the

Corn laws would enable manufacturers to pay lower wages, he

was one of many Chartists who were alienated by Thomas Cooper’s tactics.

He was the author of essays on "Wages" and " National Secular Education"

(1852) and wrote verse which was published in the Leicestershire Mercury.

Burden also opposed the levying of church rates. The Tory Leicester Journal

reporting that during the Church Rate meeting of St Mary's Parish:

A man named Burden, a Socialist, who also belonged to the

conscientious clique, opposed the rate upon principle; he did not approve of

such an establishment being kept up, and after rambling on for some time to the

disgust of all present, declared that he would not send his children to the

Church school, or, in fact, to any other school, where they would be taught to

"submit to their Spiritual Pastors and Masters."

In 1842, William Burden was secretary of the

Labourer's Friend Society which later became the Leicester Allotment

Society. He was the first to urge turning Freeman's Common into allotment

plots and he saw

allotment gardens as a way of avoiding destitution. His society adopted

what was called the

Cottage Garden Plan and the deputies of the town's Freemen were urged to

use their land on Freemen's Common for allotments and this was begun

in 1843. The town council was also asked to do likewise and land was

rented in Gaol-lane. Thomas Cook was also

involved with the Allotment Society for a time. By 1846, 100 acres of land

was occupied as allotments.

Within the last few weeks the

appearance of this locality has wonderfully altered for the better.

Instead of now beholding, formerly, one unvaried patch of grazing ground,

there is presented to the sight numerous and beautiful summer houses, and

plots of garden laid out and planted with taste and effect. By far the

greater part of the common is in progress of cultivation, and we doubt

not, ere summer comes it will present one of the most delightful places of

attraction the neighbourhood. Many of the occupiers have spared neither

labour nor expense in order to give a pleasing tone the general

appearance, and is confidently anticipated that it will be more like one

well-ordered garden than a number of allotments nor there any fear but

that in future, it will be the favourite promenade for the inhabitants of

the town. (see also Lawrence Staines)

On his death, aged 45, the Leicestershire Mercury

described him as a good and

true man .... well known as a thoughtful and worthy representative Working

Men's views and feelings. His wife Catherine died in 1882.

Sources: Leicestershire Mercury,

22 February, 18th April 1840, 2nd January,

24th April 1841, 28 May, 18 June 1842,

20th April 1844, 17 January, 29 August

1846, 10 April 1847, 26 February 1848,

21 May 1853, Leicester Chronicle,

22 April 1843, 9 March 1844, Leicester Journal, Friday 15th October 1841,

Leicester Journal, 23rd June 1882

|

|

Born:

Failsworth, Lancs. 1853, died:1934 (I.L.P.)

Burgess

was from Manchester and went to work at the age of 6 in a card-cutting

workshop. His first wife died of TB aged 21. He worked in the hosiery

trade and founded the short lived labour newspaper The Oldham Operative

in 1884, he then worked for the ‘Cotton Factory Times and Workman’s

Times.’ He was a member of the I.L.P.’s First national Administrative

Council.

“Joseph Burgess editor of the

“Workman’s Times” was requested by the Socialists of Leicester and a

majority of the Trades Council to contest the bye-election as an

Independent Labour Candidate. Burgess agreed and the I.L.P. threw

themselves into the work in a vigorous fashion, and the funds for the

campaign were furnished by the ‘Clarion,’ ‘Labour Leader,’ ‘Workman’s

Times’ and ‘Weekly Times and Echo,’ which had been appealing for weeks

past for funds for a bye-election. There were only six days for the fight.

An immense amount of work was done, the local Labour men working rapidly.

Broadhurst and Hazell got in (Liberals), but Burgess polled 4,402 votes.

And so the movement spreads.”( Tom Mann)

In 1895, Joseph Burgess contested

the general election polling 400 less votes than the year before.

Apparently, the I.L.P. had caused some offence to some electors by

conducting election meetings on a Sunday.

Burgess' radicalism ended

ignominiously, he resigned from the ILP in 1915 following its

opposition to the First World War and then became a supporter H.M. Hyndman's

National Socialist Party. In 1917, he was dispatched to Leicester to

canvas support for a candidate to stand against Ramsey MacDonald and

returned the following year to support T.F. Green, the pro war,

anti-MacDonald candidate.

Sources: Justice 14th June 1917, The Labour Annual for 1896,

Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

|

Born:

? died: ? (National Union of Railwaymen)

E. Burns became president of the

Trades Council in 1915. In November 1916, he presided over a conference on

Adult Suffrage in Leicester addressed by Sylvia Pankhurst. He moved that

"That this Conference, realising that all men and women have an equal

claim to the franchise, calls upon the Government to introduce, not a

Registration Bill, but a Franchise Bill, to give a vote to every man and

woman who has reached the age of twentyone years." In doing so he

mentioned that a very similar resolution had recently been passed

unanimously by the Trades Council.

Sources: Woman's Dreadnought, 2nd December 1916

|

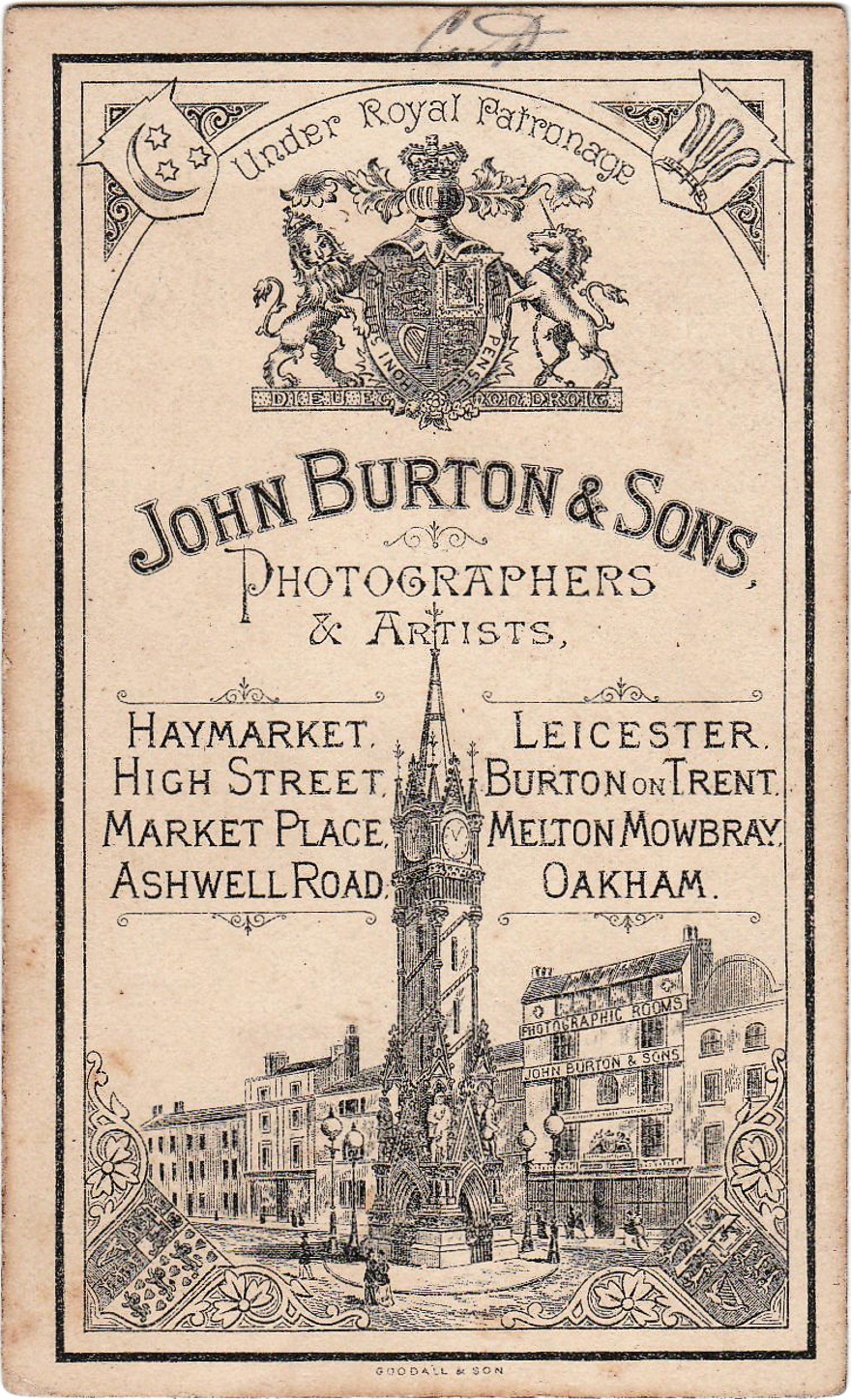

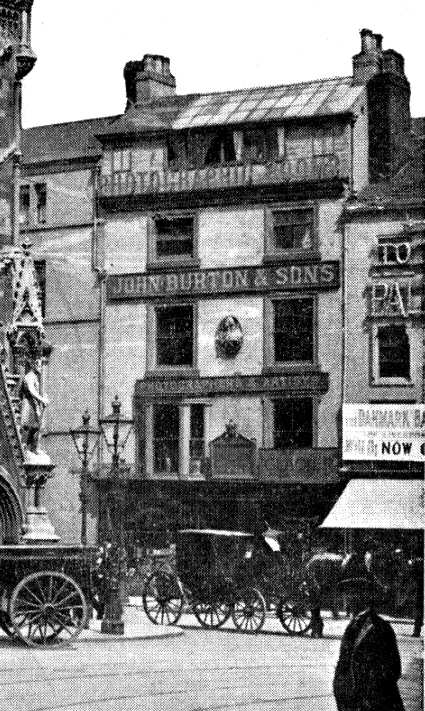

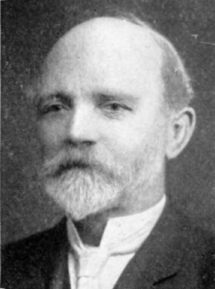

Burton's shop

at 3 Haymarket after the building of the Clock Tower.

John Burton's

memorial in Welford Road Cemetery |

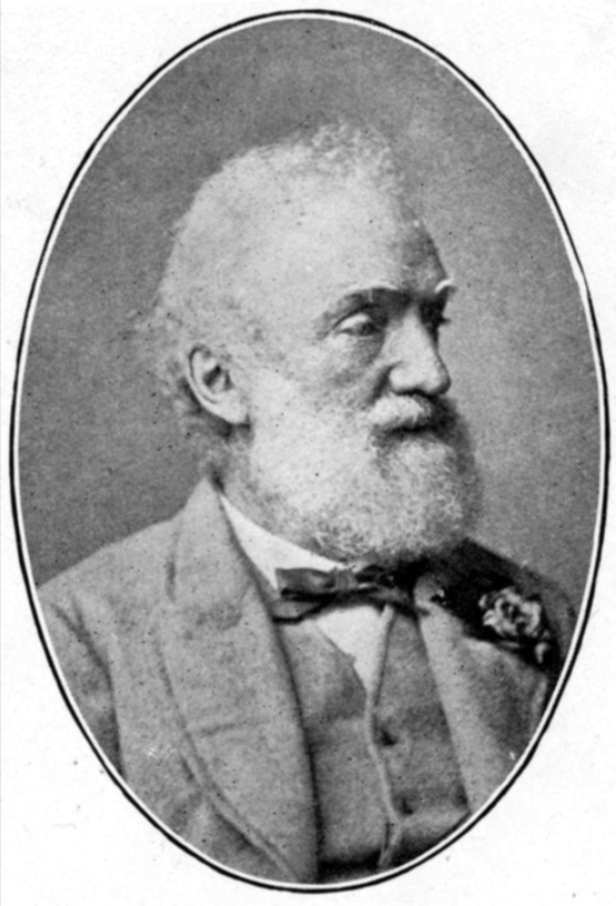

Born:

Collingham, Nottinghamshire 1808, died Leicester 1881 (Radical

Liberal)

John Burton was a printer and bookbinder by trade. He is best known for his photographic studios

and as the prime mover in the building of Leicester's Clock Tower. However,

as a 'Biggsite' radical he also played a very active part in the public

life of Leicester. By 1839 he was one of the two secretaries of the Leicester Mechanics'

Institute and continued in association with Institute for many years.

Burton was the son

of a Leicester schoolmaster, John Burton (1773-1822) who composed the hymn "Holy

Bible, book divine" which was well known at the time.

In 1841, Burton moved from his Southampton

Street premises and set up in business at 3 Haymarket, just opposite today's

Clock Tower. (It can be seen on the carte de visite on the left) In 1843, he became the proprietor of the

Leicestershire

Mercury which had previously had something of a chequered career. The paper's

first proprietor Albert Cockshaw

became bankrupt in 1840 and his successor, H.A. Collier, had lost a small

fortune. Although his tenure at the Mercury was brief, Burton had more success with the

paper than the previous proprietors. In contrast to the Whig supporting

Chronicle and the Tory Journal, the Mercury was decidedly radical in its

politics and Burton outlined the principles of the paper as being the:

faithful advocate of Complete Political Enfranchisement, or Representation

co-extensive with Taxation - of the unrestricted Freedom of Commerce and

Labour - and of the entire Freedom of Religion from any connexion with, or

control by, the state. Initially the day to day running of the paper

was placed in hands of W. S. Darkin, whilst Burton gave his attention to

his stationary business. However Darkin retired through illness and Burton

was editor and printer from May 1844 until February, 1846.

Burton's shop had a range of products beyond the usual

items of stationary

including sheet music, violins, fifes, cellos and accordions. In 1846, he

advertised a huge range of quack medicines including:

The Original Widow Welch's Female pills, Enouy's Pills for Small Pox,

Hooping-cough and Croup, Dr Stolberg's Voice Lozenges, strongly

recommended to Clergymen, Ministers, Singers, Actors and Public Speakers

and the Poor Man's Friend, or Ointment of Many Virtues for Ulcerated Legs

and Eruptions every description. From the 1850s, the shop also stocked a

wide range of artist's

materials.

In 1844, Burton published a plan of Leicester and this

street map was later used for the yearly reports by the Medical Officers

of Health to show the location of deaths from various diseases. In 1846, he

issued a prospectus for "Leicester Illustrated" which was to be a set of

engravings of the town, though it seems that only a couple of prints were

issued. He published a number of radical pamphlets and made at least one

of the illustrations, a book plate, in

Thomas Emery's Comic History of Leicester (1851) which he

published. In 1847

Burton sold his interest in the Mercury to George Smallfield, who remained

as sole proprietor and editor until February, 1854. Under Cockshaw and

Collier the Mercury had been sympathetic to the Chartists and

although Burton favoured complete suffrage, Burton and Smallfield gave

John Biggs the Mercury's support and tended to ignore the Chartists.

Burton had a strong interest in the arts and with John

Flower, he became the secretary of the Leicestershire Art Union (later

Leicestershire Fine Arts Society). This held its first exhibition in

December 1849. The Society attempted to establish a permanent art

gallery on the upper floor of the Town Museum, but this was frustrated by

the Literary and Philosophical Society who effectively torpedoed the idea.

Burton was very active in Liberal politics and was chairman

of the Middle Margaret's Ward Liberal Committee. He would have stood for

election to the Town Council, but was not eligible since he held a

contract with the Corporation. At Whitsun 1853, the was a huge

demonstration to mark the defeat of a Tory sponsored petition designed to

unseat the town's two radical MPs, Gardner and

Walmsley. Burton hung

festoon across the road (from today's T.K. Max/Body Shop to the Clocktower) with

flag pendent from the centre on which was inscribed "Truth Triumphant."

The Mercury commented that:

"Whether these words have any revolutionary

or insurrectionary or treasonable or murderously esoteric meaning in them

(i.e. to Tory eyes)" we are unable to say. Certainly it is, that the fact

of this festoon and flag being fastened by a rope to the house of Mr.

Burton, subjected him to a domiciliary visit from well-known Tory

magistrate, accompanied by a policeman."

Burton refused to take it down and his continued support

for the radical cause was shown in 1857 when he was one of many

speakers a demonstration following the defeat of Sir Joshua Walmsley. He

siad that the defeat was "accomplished by a combination so unnatural,

so dishonourable, that the participants themselves must forever feel it to

be a blot on their political character." He was referring to the

former radicals Winks and Mursell

who had thrown in their lot with the Whigs on the issue of keeping the

Sabbath holy. That year,

Burton became the

Secretary of the new Leicester Liberal Electors' Association which was the

mainspring of support for the Biggsite radicals in Leicester politics.

Burton was also John Bigg's printer.

Firth, also a bookseller and stationer, had opened a

photographic studio on Granby Street c1856. In 1858, Burton followed

suite and was assisted by his sons Walter and Oliver who described their

occupations as 'photographer' in the 1861 census. In 1862, they formed the

firm of John Burton & Sons and from 1863 they adapted their premises as a

"Salon for the Exhibition of Photographic Art Productions of every Class."

The top floor of his shop had roof lights and large windows to facilitate photography.

The business was successful and studios were opened in Birmingham, Derby

and Burton-on-Trent. In December 1862, Burton advertised a "large

photograph, painted in oils, of the 'Directors of the Midland Railway'

which was put on

view at his premises. Over painting photographs was one of the services

advertised by the Burtons.

Burton was a persistent campaigner for the embellishment

of the town and his achievements have left their mark on the face of

modern Leicester. In 1862, his campaign against the "Eastgates

obstruction" met with success when the pile of buildings which were

regarded as a great obstruction, eyesore and danger, were purchased by the

Corporation and then demolished. Burton then came up with the idea

of a monument, to stand in its place. The money was raised by public

subscription and following the removal of the Haymarket to Humberstone Gate the Clock Tower

was built, being completed in 1868.

Burton's skill as a fund raiser led to the erection of the

statue to Robert Hall in 1871. Following John Biggs' death, Burton

advocated that the town should have a statue of Biggs too. He was a popular figure

and many radicals helped raise funds for the

project. The marble statue of Biggs was unveiled on 15 April 1873 by the

sculptor, George Lawson.

John Burton married Martha Neal and together they had at

least four sons - Alfred Henry (b. 1834), Walter John (b. 1836), Oliver

(b. c.1841) and John William (b. 1845). All four sons were trained in

their father's business. The studios in Birmingham and Derby closed around

the time Walter and

Alfred Burton emigrated to New Zealand where they

became very successful photographers. Martha Neal

died in 1858 and he married Mercy Neal in 1859. He is buried in Welford

Road Cemetery plot uE 732.

It would seem that Burton's negatives, including

significant large format pictures of Leicester were recycled for the

glass during World War I.

Sources: Leicester Journal, 14th December 1849, Leicestershire

Mercury 30th December 1843, 12th December 1846, 25th October 1851, 21st

May, 3rd December

1853, 11th November 1854, Leicester Chronicle, 22nd July 1857, 13th June 1868,

12th February 1881, R. H. Evans, The Biggs Family of Leicester

LAHS 1972-73, Brett Payne & David Simkin, Derbyshire Photographers'

Profiles, Derek Fraser, The Press in Leicester c1790-1850

|

C.W.S. Duns Lane factory in 1949

C.W.S. Wheatsheaf Works, Knighton Fields

in 1892 |

Born:

Brackley, Northamptonshire 12th October 1833, died: March 1921 (Liberal, Co-operator)

John Butcher's father died when he was three

and he was taken charge of by his grandfather, a highly-respectable shoe

manufacturer in Brackley. John was sent to a local academy at an early

age, and received what was considered at that time a liberal education. On

leaving school he learned the trade of shoemaking.

In 1863, he moved to Banbury, where

he became secretary of the Temperance Society, and in that and following

year organizing a series of working men's demonstrations in favour of

total abstinence. He also joined the National Reform League in 1863 and

became very active

in the campaign to extend the franchise. With

others organized a great torchlight procession and public meeting, which

was addressed by the former Chartist Ernest Jones. He had also been

influenced by Robert Owen's idea which led him towards the ideas of

co-operation.

In April, 1866, John Butcher was one of the

instigators of the Banbury Co-operative society. He was

no 1 member and was appointed secretary at the

first meeting, continuing to hold that office until he moved to Leicester.

In 1872, he chaired a meeting in support women's suffrage in

Banbury.

Along with people like

Lloyd

Jones, he argued that the C.W.S. should start manufacturing goods for

local co-operative societies and published (with William Bunton)

the “Banbury Co-operative Tracts."

The CWS was already manufacturing

biscuits and he told the board that “biscuits were a luxury and boots

were a necessity” and advocated that a boot and shoe

factory be set up in Leicester. His advice was taken and in September 1873, the CWS

opened a boot factory in Leicester in

Dun's Lane with Butcher as manager.

That year he was elected to the Board of the Co-operative Congress.

He became the driving force behind

the expansion of co-operation in Leicester the 1870s. In January 1873, he

proposed the construction of a Co-operative Corn Mill to run on a Federal

principal, which was designed by Thomas Hind. He was a member of the board

of Leicester Co-operative Society and in 1875 he persuaded the board to buy

a block of property on High Street where a larger department store could

be built. This was also designed by Thomas Hind.

Managed by Butcher, the

West End shoe works rapidly expanded and became the principal supplier of

footwear to every retail society in the country. Butcher left Dun's Lane in

1878 and became the director of Freeman, Hardy and Willis and in 1880 he

became a partner in E. Jennings and co. On the death Edwin Dadley

in 1885, he was persuaded to return to manage the CWS factory.

By

the late 1880s, the capacity at the Dun's Lane and Enderby factories could

not meet the demand for CWS boots and shoes. In 1889, Butcher visited

America and saw the latest shoe making machinery and American methods of

shoe production. The ideas he brought back were

utilised in the

vast new Wheatsheaf Works. Equipped with modern machinery. it opened in Knighton Fields

in 1891 with Butcher in charge.

John Butcher believed that the mechanisation of shoe making in factories

brought benefits both to the workers and to the public. In an article on

Shoe Machinery in the CWS Annual of 1890, he decried the opposition of

older workers to the new processes:

"It had been the custom to “close” the seams of boot and shoe uppers by

hand. With the “clams” between his knees, holding the upper in position,

and with bent back and straining eyes, the closer plied his awl and

threads the day through; and wife and children, if he had them, plied

theirs also, all for a meagre wage. The sewing machine came in. It

threatened the closer; he feared it, and appealed to his fellow workmen to

strike against its use. He could not foresee what a lightener of toil it

was to prove; what a means of escape from a form of labour that was

unhealthy as it was ill paid; that robbed his home of comfort and his

children of the opportunities of education, while it warped their young

bodies and hindered their development."

He contrasted the days of the dull and dirty garret workshop with the

modern factory where machinists and fitters were "working in a clean,

well-lighted, wholesome apartment, and will, likely as not, be singing in

unison as they work, making labour a pleasure."

Butcher's determination to expand the CWS with new

factories equipped with the most modern machinery, sometimes brought him

into conflict with the workforce - as did the use of country labour in the

finishing processes.

Butcher had helped the inception of Equity Shoes and he

had also assisted in their discussion of mechanisation by letting their

committee look at the machinery at the Wheatsheaf factory. However, he was

not a supporter of the labour

co-partnership idea. It was "the creation," he said, "of an

aristocracy of labor." In his opinion, the duty of co-operative

manufacturers was to get the goods to the consumer at the cheapest possible

price, and "they have no right to make this price dearer by paying more

than the market rate of wages."

Jimmy Holmes saw Butcher's mechanisation programme as an attempt by Butcher to

‘smash the Equity’ and there were also claims that the CWS had brought pressure on several

leather suppliers to cut supplies to the infant co-operative. Butcher

denied this and the claims are not repeated in the official histories of

Equity.

In 1899, the trade union leader

William Inskip

returned from a tour of factories in the U.S.A. and said that "I am of

opinion that the Co-operative Wheatsheaf Works, Leicester, so ably

presided over by Mr. John Butcher, ..... are far superior examples of a

model factory.... both for the sanitary arrangements and conveniences for

the workpeople.... "

From 1883-1891, he was a Liberal Town

Councillor for North St Margaret's Ward. He was largely instrumental in

removing the Wednesday Market from Highcross Street to the Market Place.

He attracted a degree of notoriety with his support for the opening of the

Museum and Free Library on Sundays, but won the day. He chaired public

meetings addressed by Charles Bradlaugh and G.J. Holyoak as was closely

associated with the secularists.

John Butcher was a friend of

Joseph Arch and the Rev. Page Hopps, he was always a keen Liberal,

advocate of temperance, a Free Trader active in the Workmen’s Peace

Association and an opponent of vaccination. He was secretary of the

Leicester Liberal Club in 1889 and also

founded Semper Eadem freemason's lodge. He was a member of the Board of the Leicester

Co-operative Society for many years, active in the Co-operative Union and

was also on the board of the Leicester Co-operative Hosiery Manufacturing

Society. He retired from the C.W.S. in 1904. He died aged 88 and was

cremated. Despite his association with the Secular Society he was given a

religious funeral.

Sources: Banbury Guardian 31st October 1872, The Beehive 3rd July 1875, Leicester Chronicle 15th December 1877, 14th April 1883, 8th

April 1899, Leicester Daily Post 7th & 11th March 1921, Leicester Co-operative Society, (1898) Co-operation in

Leicester,

Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism,

Henry Demarest Lloyd: Labor Copartnership, (sic) 1898 , Percy

Redfern, The Jubilee History of the C.W.S., Elizabeth Crawford:

The Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland, A Regional Survey

|

| |

|

|

Back to Top |

| |

© Ned Newitt Last revised:

September 13, 2024. |

| |

Bl-Bz

Leicester's

Radical History

These are pages of articles on different

topics.

Contact

|