S

|

|

|

Born: April 1941, died: Leicester, January 28th 2018 (Indian Workers Association (GB) and Indian Association of Communists

Avtar Sadiq was a longstanding and leading member of the Indian Workers' Association and Association of Indian Communists. Sadiq, who settled in Britain in 1964, was a qualified teacher, gained a certificate in youth and community work from Leicester University and an MA from the University of Warwick. For many years he was a senior executive officer for the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE), retiring in 2002 .

He was the former National President and Senior Vice President of the Indian Workers’ Association (GB) and served as the Secretary of the Association of Indian Communists in UK . He was one of the founder members of the Progressive Writers’ Association, an ideological theoretician, prolific writer, poet author of numerous books in Punjabi. His acclaimed literary works received international recognition most recently at an event on Nationalism and Culture in Chandigarh in 2017. His books include: Sooraj Charan Tak and Sangarsh da Parteek: Cuba. The latter is a travelogue which arose from a delegation to an international solidarity conference.

During the 1970s, Avtar Singh and the IWA played a very prominent role in various broad anti-racist alliances like the Inter-Racial Solidarirty Campaign. He was an opponent of the war in Iraq and was a supporter of the Cuba Solidarity Campaign. He believed the religion should be a private matter and not something in which governments should be involved.

The IWA (GB), based within the British Punjabi community, has a long record of case work, welfare and social work, campaigning against state racism, miscarriages of justice and racist violence. The driving force behind much of activity was the lesser known work of Indian born communists who made their home in Britain.

After the Indo-China war in 1962, the pro-Chinese faction with the CPI broke away to form the Communist Party of India (Marxist). This split in India was reflected in Britain where most of the Indian Workers Associations in the Midlands allied themselves with the new CPI (M). They became the IWA(GB) as opposed to the IWA (Southall). IWA activists, like Sadiq had considerable standing amongst British Sikhs, however their principled opposition to the virulent demand for an independent Sikh state in the mid 1980s led to a substantial loss in support from within their own community.

After the demise of the CPGB, the IWA and the Association of Indian Communists developed a close relationship with the Communist Party of Britain. Avtar Sadiq frequently spoke at CP(B) events. In the 2010 general election, he stood in Leicester East against Keith Vaz on behalf of the now defunct Unity for Peace and Socialism (UfPS) which was an electoral front for the Communist Party of Britain. He obtained 494 votes (1%) which was a good result for the CP(B).

In 2017, he received a Race Equality Achievement Award as part of the Race Equality Centre's 50th anniversary.

Sources: Indo-Brit obituary, personal knowledge

|

|

Born: Stafford, c1864 (I.L.P., Labour Party & Coalition)

John Stanton Salt’s early schooling was very limited, starting work in the shoe trade at the age of 11. At 14 he became an apprentice clicker and moved to Leicester at the end of his apprenticeship. On arrival in Leicester, he became a member of the Liberal Club, joining the I.L.P. when it was founded. He worked at Stead and Stimpsons, Thomas Crick and Thomas Browns.

He was a founding member of NUBSO No 2 branch and was associated with the formation of the Leicester Self Help Boot and Shoe Manufacturing Society in 1895. He was elected to the Board of Guardians in 1907 and to the Town Council in 1910.

Following the refusal of the Labour Party nationally to support the candidature of George Banton for parliamentary by-election in 1913, he backed Hartley, the British Socialist Party’s candidate. In August 1914, he spoke on the I.L.P. platform in the Market Place to oppose the war. By 1918, he had changed sides and publicly supported the pro-war, anti-Labour, coalition candidate. As a result, he was expelled from the Labour Party in 1919. However, he was re-elected to the Council for Aylestone as a Coalition candidate in 1920.

Sources: Leicester Pioneer, 23rd March 1907, Leicester Pioneer 7th August 1914

|

|

Died: February 1840 (National Association for the Protection of Labour)

Sansome was a framework knitter and became chairman of the N.A.P.L. in 1831. Established in July 1830, with John Doherty as the first secretary, the National Association for the Protection of Labour was one of the first attempts to create a national trade union centre in Britain. It quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions spread across the five counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derby, Nottingham, and Leicester, but the organisation seems to have faded in 1832 as a result of internal dissention.

Sansome was a prominent supporter of the Reform Bill and of a working class alliance with middle class reformers, though with the passing of the bill, the alliance fell apart.

In 1833, Sansome, told the Children's' Employment Commission that most knitters worked a seventy-hour week, five days at about 14 hours a day, but he added:

We work, however, when we please; each man has full liberty to earn what he likes, and how he likes, and when he likes; we have no factory bell; it is our only blessing.

Sansome was a champion of the ten hours bill and in the 1830s kept the Union pub in Wharf Street where a union of framework knitters was formed. He was known as 'Ned Samsome the Spouter.' In 1833, he hosted a dinner at his pub pub on Wharf street to celebrate the liberation of Richard Carlile from prison. The Carlile's Gauntlet gave this report on his speech:

The politics of Thomas Paine had done much good: even with all and every prohibitory drawback which the government wielded to keep the people from reading his works, still they had found their way into the hands of that portion of the people whom it had been most desired should know the least about them. But the time had arrived when to talk about suppressing a book was to talk about an impossibility. He concluded a very able speech by proposing “the memory of the immortal Thomas Paine.”

Along with John Seal and Thomas Ryley Perry, in 1833 he was active in support of a teetotal working class reading room. In 1836, he spoke in opposition the the new Poor Law, but was anxious to say the law was the product of 'monied world' rather than that of the radicals.

By 1838, this 'king of the working classes' as he saw himself began to be regarded with disdain by some Radicals like John Swain, who believed the Whigs sent him to disrupt Chartist meetings or that he was just not right in the head. The latter turned out to be true since from 1838, his health declined and he was committed to the lunatic asylum and was reportedly in a 'childish state' before his death.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle, 20th November 1830, 18th June 1836, The Gauntlet, 27th September 1833, Leicestershire Mercury, 13th August 1836, 24th November, 1st December 1838, Leicester Herald 7th March 1840, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954

|

|

Born Sleaford Lincs c1849, died October 1908 (Hull Women's Liberal Association & I.L.P.)

Mrs Saunderson was both the first person from the Independent Labour Party and the first Labour woman to be elected to public office in Leicester. She was also the first woman to be elected to the Hull School Board where she had lived before coming to Leicester. In Hull, she was one of the founders of the Women's Liberal Association and was active in the Women's Emancipation Union. In the 1880s, she spoke at public meetings on the issue of votes for women and frequently wrote to the local press. Sometimes known as Mrs Ashton Saunderson, she also tried to set up a Labour register to help the unemployed and spoke at a meeting of dockers' wives during the 1893 dock strike. She moved to Leicester with her husband because of his work - he had a shop in Great Central selling paint and varnish. She was adopted as an I.L.P. candidate for the school board in Leicester and was elected in December 1894.

Her election campaign was assisted by what was described by the Clarion as "the Lantern Parade." This consisted of a 4ft square wooden frame with sides covered in white linen - like a box open at the top and bottom. Slogans were painted on the sides in colours, and a cross-bar was put in the middle with a naphtha lamp. Two pieces of wood about 8ft. long were fastened inside and this was carried in the air over people's heads. The light from the lamp showed up the painted inscriptions. This attracted crowds and at street corners meetings were held with the aid of a chair or portable platform.

She told an election meeting that year that she believed not only in non sectarian education, but also in Secular education. She believed that since some scholars were the children of parents who were not Trinitarians, and as the Scripture teaching contained the doctrine of the Trinity, she considered it was not fair this should be forced upon them. ..... she would be glad to see Bible teaching abolished altogether and something else put in its place..... one of the most desirable of which would be English grammar, which was not at present taught in the schools under the Board. She considered that religious instruction might very well be left to parents and to Sunday-schools

She believed in physical as well as intellectual education, and for this reason was in favour of gymnasiums and swimming-baths being attached to the schools in every district for the use of the children.

She was lambasted by the Leicester Chronicle for being ignorant of the conditions of Leicester and for wanting to preach Socialism and abolish bible teaching altogether. In December 1895, she resigned from the Board and appears to have dropped out of political activity.

Sources: Hull Daily Mail, 28th March 1887, 8th June 1892, Leicester Chronicle, 1st December 1894, The Wyvern, 6th December 1895, Gerald Rimmington, Education, Politics and Society in Leicester, 1833-1903, Hull Daily Mail, 17 January 1893, Leeds Mercury, 28 April 1893, Clarion, 15 December 1894

|

|

Born Leicester 1883 (Labour Party)

Edith Scott was a bookbinder and joined a union in 1914. By the end of the First World War she was become an organiser for the National Union of Printing and Paper Workers. She was an unsuccessful Labour candidate in the local elections of 1919 and 1920 in Newton Ward. She argued for involvement of women in the design of the new council housing. However, she did not stand again and continued her trade union work until she retired in 1943. In 1930, she opposed a proportion of her union’s executive being reserved for women. She said

“We are not prepared to accept any favours from men. If we are to be elected to Council, we want to go there by virtue of the democratic vote”

She was a delegate to the Trades Council from the Printing and Paper Workers and in 1935 became its first woman president. She was still a delegate in the early 1970s.

|

|

Died: December 1988, aged 73 (Labour Party)

Bill Scotton was a former Chief Petty Officer in the Royal Navy where he had spent 17 years. (1929-45) He became district organiser of the Union of Post Office Workers and was first elected to the City Council for Belgrave in 1963. He subsequently represented De Montfort and Charnwood (1971-1981). In the early 1970s he was chairman of the City’s Traffic Committee which was responsible for some of the road including the controversial Eastern Relief Road. This was approved three times by the City Council before being dropped by the County following reorganisation. He did, however, ensure that Waterloo Way passed underneath New Walk, rather than going through it as originally proposed. He became Lord Mayor in 1979.

|

|

Born Leicester c1786,died 23rd January 1851 (Owenite, Chartist & Radical)

John Seal was a newsagent, bookbinder and small bookseller in Town Hall Lane. He sold newspapers and pamphlets “advocating the just rights of the wealth-producing millions and opposing the aggrandisement of the non-producing few.” Under Robert Owen's influence, the No1 Co-operative Society was set up in Leicester in c1830 and John Seal became the manager of the Co-operative Store which opened in Church-gate. It had about 200 members.

"The system being one which it was hoped would prove of great advantage to working people, loans were solicited from the opulent classes to aid in carrying it out. Among the number who responded to the appeal was Lady Noel Byron, who, with her wonted benevolence, sent Seal five pounds for that purpose. After some months' trial, however, it was found that the shop in Leicester did not answer, and it was given up. Seal, soon after, owing to the want of employment, became very much straitened in his circumstances; but, though he had the five pounds in his possession, advanced to the concern by Lady Byron, while thus situated his high sense of integrity would not allow him to make use of a shilling of the amount to meet his own wants, and having ascertained Lady Byron's address, he immediately afterwards transmitted the bank note, unbroken, to her ladyship. This affords an instance of a remark once made by Lady Byron that she had lent hundreds of pounds to the poor and had scarcely lost a shilling in so doing."

In 1831, a Co-operative in Dover street selling groceries had been in operation for a year. It is not clear whether this was a separate co-operative. In 1832, a delegate from the No 3 Co-operative society in Leicester gave a report to a meeting Birmingham. Seal, along with his brother Richard, were active of Thomas Ryley Perry during his imprisonment for selling the unstamped press and was sympathetic to the ideas of Richard Carlile. He in 1833, he wrote to Carlile that:

It is now as clear as the sun at noonday, that the productive population of this country will be disappointed if they expect any relief from the present mock reformed House of Commons. The men who were so loud and clamorous in their denunciations of the Tories for their Coercion Bills, their shacklings of the press, and other oppressive measures, now not only support and confirm such measures, but add insult to oppression.....,

John Seal became the secretary of the Leicester Working Men’s Association founded in August 1836. That year he told a meeting that:

while the wealthy and middle classes were alone represented in Parliament, their interests would receive the greatest share of attention in all measures of legislation, to the neglect of the poor. Session after session, laws were made in which the working classes, the great mass of the community, were overlooked; and this would continue to be the case, till they had a fair share in the representation.

The original programme of the Leicester Working Men’s Association did not go beyond household suffrage, the ballot and triennial Parliaments. However,along with John Markham, he reorganised the Association based on the principles of the People's Charter. In 1840, he was secretary of the Chartists and was the publisher of the Midland Counties Illuminator on behalf of a managing committee.

He also became a supporter of Robert Owen and in 1838, he took bookings for the use of the room at the Social Institution. In 1842, he broke with Cooper’s Chartists as a result of Cooper’s policy of co-operation with the Tories. He denounced Cooper as a political impostor and a Tory Chartist. Thereafter, he became active in the Leicester Complete Suffrage Association. On his death, he was described as

"an advocate for the fullest and freest inquiry into every matter interesting to the inhabitants of a free state; but for several years he bad ceased to take any public part in any of the great movements of the day; partly in consequence of the infirmities incident to advanced years."

Sources: Leicester Journal, 2nd November 1832 27th July 1838, The Gauntlet 22nd September, 22nd December 1833, Leicestershire Mercury, Leicestershire Mercury, 13th August 1836, March 31st 1838, 26th June 1841, 25th February, 5th March 1842, 1st February 1851 Leicester Chronicle, 13th March 1830, 19th May 1832, 30th July 1836, 1st February 1851, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

John Seal in 1860

|

Born 18th March 1789, died 5th November 1869 (framework-knitter, Chartist & Radical)

Richard Seal was the younger brother of John. He enlisted in the Leicester Militia in 1810 and served in Enniscorthy, Ireland. In 1813, he volunteered for the 40th Foot and saw service in in the Peninsular War of 1808-14. He was present at the action on the Pyrenees; then at Orthes, and then at Toulouse. From Spain, the regiment was sent to the United States, but was too late to take part in the battle of New Orleans. On his return to Europe in May 1815, he took part in the Battle of Waterloo. He was then promoted to sergeant and left the service.

In the late 1820s, he became a leader of the local framework knitters and a rival to William Jackson also a local leader. In 1825, the Leicester Chronicle reported a speech he made to strikers, saying that morning he had come from the treadmill in the Bridewell where he had been imprisoned for a month for 'neglecting his work.' (going on strike). In 1830, he was prominent in the Leicester branch of the National Association for the Protection of Labour. This was the attempt led by John Doherty to form a national trade union structure.

In 1832, he was the chief working class spokesman in the council of the Leicester and Leicestershire Political Union, the organisation of local radicals supporting the Reform Bill. At this time, he boasted his readiness for armed rebellion should it prove necessary. In 1838, he was a founder, with his brother and John Markham, of Chartism in Leicester. Initially, he helped and encouraged Thomas Cooper. However, he soon broke with Cooper and remained an ally of John Markham.

Richard Seal worked for the Biggs firm and in 1848, he was a signatory to a letter defending his employer's good name. Seal was also a freeman which allowed him to vote and was active amongst the freemen's deputies in the mid 1850s in opposing bribery and treating. He lived in Metcalf Street, close to Wharf Street.

After the demise of Chartism, Seal was active on the radical wing of the Liberals which was organised through the Reform Registration Society. In the mid 1855s, he opposed attempts by the teetotallers to close pubs on Sunday. When he retired from public life in 1859, he was presented with a testimonial by the local Liberals. It was said of him that:

"From the year 1824, down to the present time, the progress of every measure having for its object the political or social advancement of the people, has been urged onwards by Mr. Seal's untiring and able advocacy. Catholic Emancipation, the Reform Bill of '32, Municipal Corporation Reform, Freetrade and the Abolition of the Corn Laws, are but a few of the measures which have from time to time enlisted his hearty support..... for whenever a position has been assailed by the opponents of political progress, Mr. Seal has always been his post, ready to give battle to the enemy."

Sources: Morning Chronicle, 23 July 1825, Leicestershire Mercury, 10 September 1859, Leicester Chronicle, 22nd January 1831, 10th March 1855, 27 June 1868, Crisis, and National Co-operative Trades' Union Gazette, May 5th 1832, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954, Census returns and Joan Rowbottom

|

|

Born: Ironbridge, Salop, 28th October 1846; died: 1934 (trade unionist)

George Sedgwick attended a Unitarian School in Birmingham and worked as a boot closer at an early age. He was secretary, then president of the Birmingham Rivetters’ And Finishers’ Society. After a period in the Worcester Rifle Corps, he moved to Stafford where, in 1867, he joined the Amalgamated Society of Cordwainers. In 1874, he helped establish the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives with Thomas Smith. He was the union’s first agent and succeeded Smith as General Secretary in 1878.

Sedgwick was a supporter of arbitration he believed that many strikes could easily settled if both men and employers could meet and talk over their grievances. In 1882 went so far as to suggest that purpose of the trade union was “to act as mediator between employers and workmen in trade disputes.” Such a conciliatory attitude towards employers ultimately foundered in the late 1880s as more disputes arose from the shop floor.

He was member of the School Board 1879-1886 and was the first chairman of the Leicester Working Men’s Club. In 1886 he was one of the first working men appointed as a Inspector of Factories. After some time in Leicester he went to Glasgow where he contributed a great deal to the Select Committee Report on the Sweating System. After a period in the Black Country, he returned as to Leicester to work as a factory inspector in 1896, retiring in 1911. When he died at the age of 87 he was the oldest magistrate on the Leicester bench.

Sources: Fox, Alan, A History of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Workers. 1958, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism

|

|

Born: Leicester, June 1927, died: December 2008 (Labour Party)

Janet was born into a family which was deeply involved in Labour politics. Her maternal grandmother, Mrs Annie Stretton helped to form the Labour League of Women in Leicester in 1906 and her parents Rowland and Molly Hill were both involved in Labour Party politics.

She was educated at Newarke Girls’ Grammar School and Leicester Domestic Science College. On leaving College, she commenced a career in catering and taught cookery in a number of schools. Janet was first elected to the Leicester City Council as a Labour Councillor for the North Braunstone Ward in May 1970. With the re-organisation of Local Government in 1973, she was elected to serve on the new Leicester District Council and also on the new Leicestershire County Council as a representative for North Braunstone.

During the late 1970s and 1980s, Janet became identified with the Leicester West group of councillors who were cautious about some of the radical policies favoured by the newer left wing members. Janet was also concerned to protect Greville Janner’s position as MP and kept a watchful eye both on the membership of the constituency and also its boundaries. Loyalty counted for much in her eyes. Not only was she very loyal to the Party itself, but she was also loyal to those with who she worked - sometimes in spite of their failings.

She served on a number of the major Committees of the City Council including Environmental Health and Public Control, Estates and Finance, on all of which she was the Chairman. She was a Governor of several local schools and of Southfields Further Education College and was a member of the Leicestershire Health Authority. She was one of the first members of the Radio Leicester Council.

During 1982-84, Janet became the first woman and the first Councillor from a City Ward to become ‘chairman’ of the County Council. She became Lord Mayor in 1985, becoming the first daughter of a Lord Mayor of Leicester to become the chief citizen in her own right and the first person to have held the offices of Lord Mayor and the 'Chairmanship' of the Leicestershire County Council.

Janet was a consistent advocate of the return of powers to the City Council and believed that the division of the City Labour Party into three separate constituency parties was a mistake. She saw the City regain unitary status in 1997, but lost her seat to the Liberals in 1999. She continued her constituency work for as long as she could and provided additional information for this series of biographies.

Sources: Leicester City Council, Roll of Lord Mayors 1928-2000, author’s personal knowledge

|

|

Born: 3rd Jan 1930, died May 1986 (Labour Party and Independent)

Krishnalal Shah was a Kenyan Asian who had first come to prominence in working for the reception of the Ugandan Asian refugees. He was also a member of the Community relations Council. He was a shopkeeper and owner of Shah’s Emporium. In June 1973, he became Leicester’s first Asian councillor. At the election count a member of the National Front poured a cup of tea over him and the Leicester Mercury ran the page one headline: ‘Leicester Gets First Immigrant Cllr.’

Ten years later, there were ten Asian councillors- all Labour. By this time, however, Kris Shah had left the Labour Party and had stood as independent against Pat Hewitt in Leicester East. In this contest, he took enough votes to ensure the election of the Conservative Peter Bruinvels.

Sources: Valerie Marett, Immigrants Settling in the City, 1987

|

|

Born Stoney Stanton circa 1836, died 1906

Jos Sharp was a framework knitter who lived on Willow Bridge Street for most of his life. He became Secretary of Leicester Secular Society c1867 and probably continued until he became the first secretary of the Trades Council in 1872. He served in this capacity until 1885 when he retired.

In its early years the Trades Council met at the British Workman Public House on New Bond Street. This in fact was a temperance institution which later moved to Charles Street. It was the venue where many trade union branches and the Republican Club met in the 1870s. In 1873, he was one of the original shareholders in the Secular Hall Company, but he could not keep up the instalments on his £5 share which he had to sell.

By the 1890s, he had a grocers shop and moved to Taylor Street.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle, 7 February 1885, Leicester Pioneer Sept 5th 1903 F. J. Gould, The History Of The Leicester Secular Society, 1900, Records of the Secular Hall Company

|

|

Born: Whetstone 3rd Sept 1908, died June 1975 (Labour Party)

Bernard Shenton was a railwayman on the LNER and a trade unionist. He was one of the first residents on the new council estate at Braunstone, living at Winton Avenue. During the 1930s, he was the secretary of the Braunstone Tenants' Association. At the time it was the second largest tenants' association in the country. He was involved setting up a national tenants' organisation, becoming the Secretary of the National Tenants' Association. He gave up the post when became warden of the Cort Crescent Community Centre in 1939. In the late 1930's he was was president of West Division Labour Party

Sources: Leicester Daily Mercury - Thursday 10 August 1939

|

|

Born c1926, (Communist Party)

Dave Shepherd was an engineer and a member of the Amalgamated Engineers’ Union. During World War Two he worked as a 'Bevin Boy' in the Leicestershire & Derbyshire mines. He was secretary of the South Leicester branch of the Communist Party from 1948 onwards. By 1960, he had stood as the Communist candidate for De Montfort ward seven times without any success.

Sources: Leicester Evening Mail 9th June 1949, Leicester Mercury, 24th April 1950

|

|

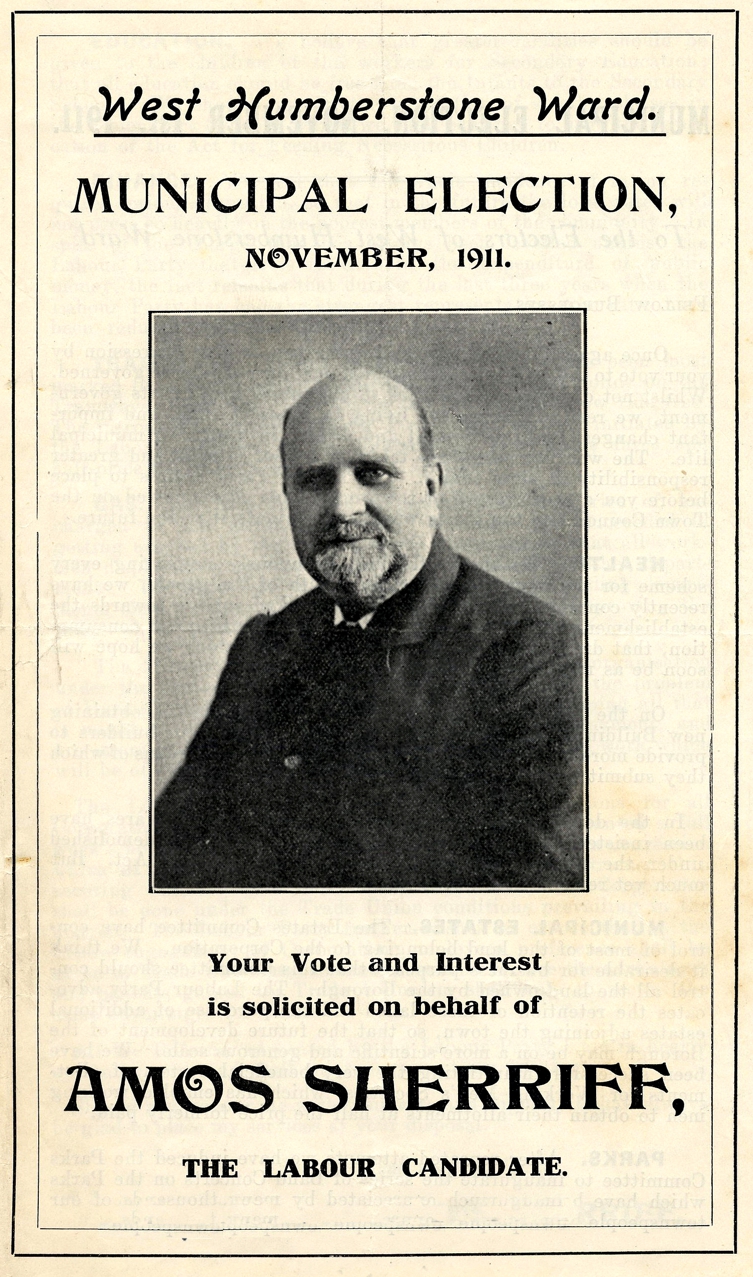

Born: Leicester, 6th Jan 1856; died: May 1945 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

Amos Sherriff was the son of a poverty stricken glove framework knitter living in Russell Street in the heart of Leicester’s slums. Amos never went to school and could not read or write until he was in his 20s. He began work at the age of 6½ and for his first twenty-five years, he worked in Mr. Fielding Moore's Spinney Hill brickworks. Aged 20, he attracted some attention when he undertook the extraordinary task of making 700 bricks by hand in an hour.

He stripped to the work, having two boys to carry off the bricks when made… and was warmly congratulated by those who had witnessed the feat, upon the skill he had shown in his trade.

In 1878, aged 22, Amos joined the Christian Mission (later to become the Salvation Army) where he received help in learning to read. With the Salvation Army, he paraded the streets, playing the cornet and preaching at meetings. In those days the Salvation Army was often unpopular, and he sometimes returned home covered with blood and mud, having been pelted with stones. Like many young Leicester socialists, his first exposure to Socialism came at a lecture by Tom Barclay. Unlike Barclay, Sherriff remained a strong Christian and temperance supporter.

Amos left the Salvation Army in 1894 and became a founder member of the Independent Labour Party, being elected to its local executive. He established a cycle shop on Belgrave Road, where people used to call to discuss their problems with him and listen to his advice. He became the central figure in the small local Clarion readers’ group, his shop being the outlet for the Clarion cycle.

In 1901, Sherriff was elected to the Board of Guardians, which administered the Poor Law. Sherriff believed that relief provided for the unemployed should not involve the stigma of pauperism. As a Guardian, he tried to prevent the unemployed losing the right to vote when they received relief and opposed the labour test which required the unemployed to do hard manual work before they received any help. He warned that “shortly the working community will rise up and wring the neck of this wretched system”, adding: “these are our own people, our own townsmen, at one end of the scale of society, while at the other end there are people rolling in boundless wealth.”

During the Boer War, Leicester’s shoe factories worked to full capacity to make boots for the soldiers. At the end of the war, unemployment grew to 15% as many workers were laid off. George White, the young crippled laster who had campaigned for better treatment for those on the "test', seized the initiative afforded by a lengthy queue of workless outside the Town Hall and led them on a march around the town. This exercise in street drama caught the attention of Amos, Sherriff who helped White organise daily processions and meetings in the Market Place. Sherriff urged the unemployed to take action. He advised them to refuse offers of relief from the Guardians, since accepting even one loaf of bread meant being taken off the electoral register for 12 months. He told them to demand that the Guardians buy land and erect workshops and pay reasonable wages without disenfranchisement; they should ’besiege’ the Council, as it had a lot of powers, if it would only use them.

Drawing on his skill as a speaker, and on his experience as a captain in the Salvation Army, he rallied the men to march to London to draw attention to the plight of the unemployed. Initially the idea of a march did not get the support of the trades unions at Trades Council. Some in the I.L.P., like Jabez Chaplin publicly opposed it, whilst others like George Banton thought it would be a risky venture which could end in disaster.

Every effort was made to organise the men before the march began. Marching was practised every day, accompanied by the ’unemployed band’, and good discipline was insisted upon. The men were warned that anyone who let ’the cause’ down by any form of bad behaviour, and especially of drunkenness, would immediately be abandoned by the roadside. Sherriff visited many of the towns on the route before the marchers left Leicester and arranged for hospitality. An extra element of topicality was added when Sherriff announced that the march was not to lobby “a cruel and heartless” Parliament, but to petition the King, taking his precedent as the recent unrest in Russia. In his view:

“.... the unemployed in England were suffering under the same conditions as the Russian peasantry; and if the King did not see them, then the press of this country would no longer be able to throw stones at the Russian Monarch.”

Several English newspapers, including The Times, condemned this idea as unconstitutional. By the time the march left Leicester on June 4th, 1905, the idea of such a protest had caught the imagination of the public and some 30,000 people gathered in the Market Place to see the 497 men set off. It was the first protest march of its kind by the unemployed and was also to set the pattern for the Hunger Marches of the 1920’s and 1930’s. It was a six-day, 100-mile march and the first leg was from Leicester to Market Harborough. They then went through Northampton, Luton and St. Albans to London. Along the way they slept in old churches and cattle sheds.

A Market Harborough barber offered free haircuts and local shops along the route provided free food, but although people were kind, not all the newspapers were sympathetic. The Times reported: “A walk to London, especially if food and shelter on the way are provided free, will always be attractive to the restless, the shiftless, or the simpletons among the unemployed and unemployable. This form of menace must be resisted. They must be assured their walk proves nothing.”

Not all the men completed the journey, bad weather, fatigue, injury and exhaustion had whittled the numbers down to 437. When the marchers arrived in London, the weather washed out the planned march and demonstration in Hyde Park. It was a sad end to a spirited venture and to make matters worse, the King refused a meeting.

However, on Sunday June 11, 50,000 Londoners turned up to honour the Leicester marchers in Trafalgar Square. Although it took another seven days, the long walk home did not feel quite as bad. When they arrived in Leicester, they were greeted as heroes with tens of thousands of people gathering in Leicester Market Place. During the summer of 1905, Amos toured Lincolnshire, unsuccessfully trying to find farm work for some of Leicester’s unemployed. As a result of his stewardship of the march, Sherriff became known in the press as ‘the General.’

The 1905 march was a remarkable effort and was successful in raising public awareness of the plight of the unemployed. Though it had no tangible results, the march highlighted the debate over the Unemployed Workmen’s Bill which came before parliament during the summer of 1905. This Act enabled local ‘Distress Committees’ to be formed. These were brought into being for the investigation of need, they could provide work, establish labour exchanges and, in suitable cases, could arrange for emigration. Their funds were partly voluntary and partly raised from the rates. Unlike the Poor Law, those it helped did not lose the right to vote. Although the Act was inadequate, it recognised the right of men to expect work, even though it did little to provide it. It was described by Lloyd George as being like “a motor car without petrol or only such petrol it could beg on the road.”

Amos Sherriff spoke at very many meetings about the march, these were illustrated by 110 hand coloured lantern slides showing the incidents of the march. Sets of postcards were also produced and they provided excellent publicity for the I.L.P., drawing a clear distinction between the Socialists and the Liberals over the injustices of the Poor Law. A plaque to commemorate the march is located in the Market Place, in front of the Corn Exchange steps. In 1908 Amos was elected as the Councillor for West Humberstone.

On Sunday 2nd August 1914, Amos spoke at a meeting in the Market Place to oppose the approaching war. He said

“If the war happens, we can expect that tens of thousands of strong men will be torn from their homes and families never to return. Just suppose that the big guns were fixed up on Big John and firing on Leicester, tearing up our buildings. You might say it was not here, but it is somewhere and it means as much to the natives of those places. War belongs to the devil and everyone who supports it must claim the devil as a parent.

Whatever is done on the Continent, England must keep clear of the bloody work. England has not got over the Boer war - there is a memorial to the dead in every town and hundred millions of debt has yet to be paid. Yet there were vagabonds about who were stirring up another war. Where were the political leaders that day? They were away and only the common people who met at street corners were left to urge Britain to keep the peace. Reason and common sense would have to be exercised when death and destruction had done their work. Why not use it now? (Cheers).”

Sherriff would have been Labour’s first mayor in 1919, but because of his opposition to the war, the Liberals and Tories combined to elect Jabez Chaplin, from the ‘patriotic’ wing of the Labour movement, mayor in his place. Amos eventually became Mayor in November 1922 and was later elected to the Aldermanic bench.

The whole of Sherriff’s political life was devoted to improving the lot of the disadvantaged and unemployed. In the years after 1905, as a councillor and guardian, he chose to work within the system rather than as a campaigner. Although heavily involved in ‘distress’ work, he played no part in the unemployed movement of the 1920s and 1930s, despite the Hunger Marches being inspired by the Leicester march.

In 1921, there was a series of demonstrations by the unemployed, culminating in baton charges by the police and a major disturbance in the town centre. This came as a result of the Guardians’ refusal to provide relief to those thrown out of work. As chairman of the Council’s Distress Committee, Amos brokered a scheme between the Guardians and the Ministry of Health which set up public work-schemes for the unemployed which were paid half in kind and money. It was later claimed that this scheme had cleared the streets of Leicester of processions of the unemployed. It gave Leicester something of a reputation for dealing with unemployment and in the late 1920s, the scheme attracted the interest of other local authorities and many deputations came to see its operation.

When, in 1928, when the Guardians were abolished and replaced by local authority public assistance committees, Amos Sherriff became chairman of the Council’s Public Assistance Committee. He campaigned for money to renovate the workhouse, now called the Swain Street institution, and tried his best to humanise the system. This was not easy when in his view the builder of the workhouse must have been told to “build something like a prison but not a prison.” Under his tutelage films like Snow White and the seven dwarfs were shown there.

Amos had always felt that the solution to unemployment lay with returning to the land. He had been chairman of the Guardians’ Farm Committee and during the 1930’s he got the Council to set up homesteads for the unemployed at Thurcaston, though they did not meet with any real success. He continued to be an active member of the Council until well into his 80s, resigning in 1944. He died in May 1945 whilst visiting the workhouse.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle, 29 July 1876, Midlands Free Press, 27 October 1894 Jo Rostron (ed) 1905 Unemployed March, Leicester City Council 1985 Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism, Jess Jenkins, Leicester's Unemployed March to London, 1905, Howes, C. (ed), Leicester: Its Civic, Industrial, Institutional and Social Life, Leicester 1927

|

|

Born circa 1877 (WSPU)

Ellen Sherriff was a suffragette and niece of Amos Sherriff who worked in the boot and shoe trade as a shoe machinist. She became the branch’s most successful arsonist. Along with Kitty Marion and Elizabeth Frisby (later a Conservative councillor and Lord Mayor), she burnt down Blaby Railway station in July 1914, causing £500 worth of damage. The culprits were never caught. Kitty Marion, (Katherina Maria Schafer) 1871-1944 was born in Westphalia and was a leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign. She was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House in Sussex (April 1913), the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse (June 1913) and various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred followed by release under the ‘Cat & Mouse Act.’ It has been calculated that Kitty Marion endured 200 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike.

Sources: Richard Whitmore, Alice Hawkins and the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian Leicester, The Papers of Kitty Marion, The Women's Library, London Metropolitan University

|

|

Born: Peebles, 23rd September 1895; died: Edinburgh 1983? (Labour Party)

In the late 1930s, Paul Shortreed lived in Narrow-Lane Aylestone and was manager of the Leicester branch of Copeland-Chatterton Co., Ltd., a business systems organisation. In the late 1930's, he was convenor of the Leicester branch of the Left Book Club. He was also active in the Co-operative movement and in 1939 was the secretary for the Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. In 1938, the Lord Mayor had a established a fund to help the refugees which stood at £350 in October 1938.

In June 1939, there were 27 refugees, including wives and children living in Leicester. They had been maintained in the homes of the committee's friends for periods of up to six months. The committee was then able to take over a house to provide extra accommodation. In 1940 , local people also supplied furniture for the hostel occupied by Czech refugees at 67 Sparkenhoe-street. The Czechs brought with them knowledge of the manufacture of glass jewellery and many were employed at the English Glass Company, Empire Road. By 1942, the refugees ran a club in Highfield street and by which time there were about 100 Czech refugees in the City.

Paul Shortreed returned to Scotland sometime before 1943 and became a Labour councillor in Dundee in 1945.

Sources: Leicester Evening Mail 4th February 1937, 21st October 1938, 16th March 1942, 1st June 1948, Leicester Chronicle 24th June 1939, 18th January 1941, 6th November 1943.

|

|

Edward Silverwood

Born , died

Edward Silverwood worked at the Abbey Mills Factory on Ross Walk. He became the first chairman of Leicester Co-operative Society before it was formally constituted in 1860

Sources: Co-operation in Leicester, 1898

|

|

Born: 26th March 1915; died: 17th January 2002 (Communist Party)

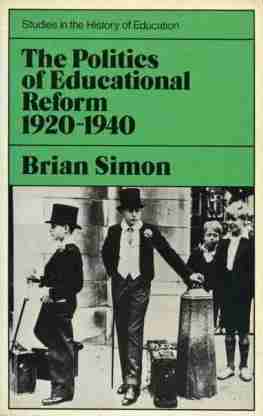

Brian Simon, emeritus professor of education at the University of Leicester, was best known for his four-volume history of the English education system and his life-long advocacy of equal secondary opportunities for all through comprehensive schooling.

In the 1950s and 1960s, he was the education spokesman for the Communist Party and called for the end of intelligence testing. His campaigning for comprehensive education, particularly through the journal Forum, was indispensable and inspiring reading during the 1960s and 1970s for many of the country's best comprehensive school teachers. He was critical of the 1956 Soviet intervention in Hungary and opposed the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. He was for a short period a member of the CPGB national executive.

Simon came from a favoured background. His father, Ernest Simon, head of the family engineering firm, was made first Lord Simon of Wythenshawe for public services, which included a long spell on Manchester City Council and service as lord mayor, during which he campaigned for - among other things - a smokeless city and better housing. Brian Simon's mother, Shena was for 50 years on Manchester's education committee, working to improve the state system. Among close family friends was R.H. Tawney, also strongly committed to secondary education for all.

As a schoolboy, Simon had encountered German fascism at first hand, having been sent in the early 1930s to Kurt Hahn's progressive school at Salem, which was already under Nazi attack. At Trinity College, Cambridge, Simon was part of the concerned generation which, horrified by fascism, turned to communism.

While at Cambridge, Simon became involved in international student politics and met his future wife, Joan Peel - a direct descendant of the 19th-century prime minister, Robert Peel. In 1939-40 he was president of the NUS, and in 1943, at the age of 27, he wrote A Student's View Of The Universities, a critique of the university system.

But this gently elegant man did not want to go into full-time politics. His aim was to become a teacher, and he trained at the London Institute of Education. Then, after war service with the Corps of Signals and GHQ Liaison Regt (Phantom), he taught in Manchester and Salford.

Five years later, in 1950, he was drawn to Leicester University School of Education, where academics were doing fieldwork devising a comprehensive school system. University staff, under the directorship of Stewart Mason, worked with the local education authority to produce Leicestershire's two-tier model, the success of which was to help make the case for the national policy announced by Education Secretary Tony Crosland in 1965. Simon became a professor in 1966, the year following the publication of what was to be the first volume of his history of English education, having already published extensively on intelligence testing and local history. He was a co-founder of Forum in 1958. In 1970, he co-authored - with Caroline Benn - a research study on comprehensive reform, Half Way There, which was based on extensive questionnaires. Simon stayed at Leicester for the rest of his professional life, retiring in 1980.

Simon histories contain some gripping accounts of local education authority battles to secure more resources for ‘their’ pupils. His work on educational psychology, some of it in conjunction with his wife, was designed to show the deficiencies of the post-war fashion for psychometric testing, made famous by Sir Cyril Burt, which divided children into grammar and secondary-modern types. When Simon retired in 1980, he finished the last of his education histories, bringing the story up to date. He also edited a number of books, including key texts from a broad range of political views designed to provide a base for a broad-ranging critique of government policy.

Simon wrote a draft autobiography, which was published in a shortened version as A Life In Education (1998). Sadly, it was pruned of the personal to focus on educational issues. Had Simon lived in a culture more tolerant of communist intellectuals, his educational thinking would surely have been recognised as mainstream earlier.

Sources: The Guardian, January 2002 (Anne Corbett) & personal knowledge

|

.jpg)

|

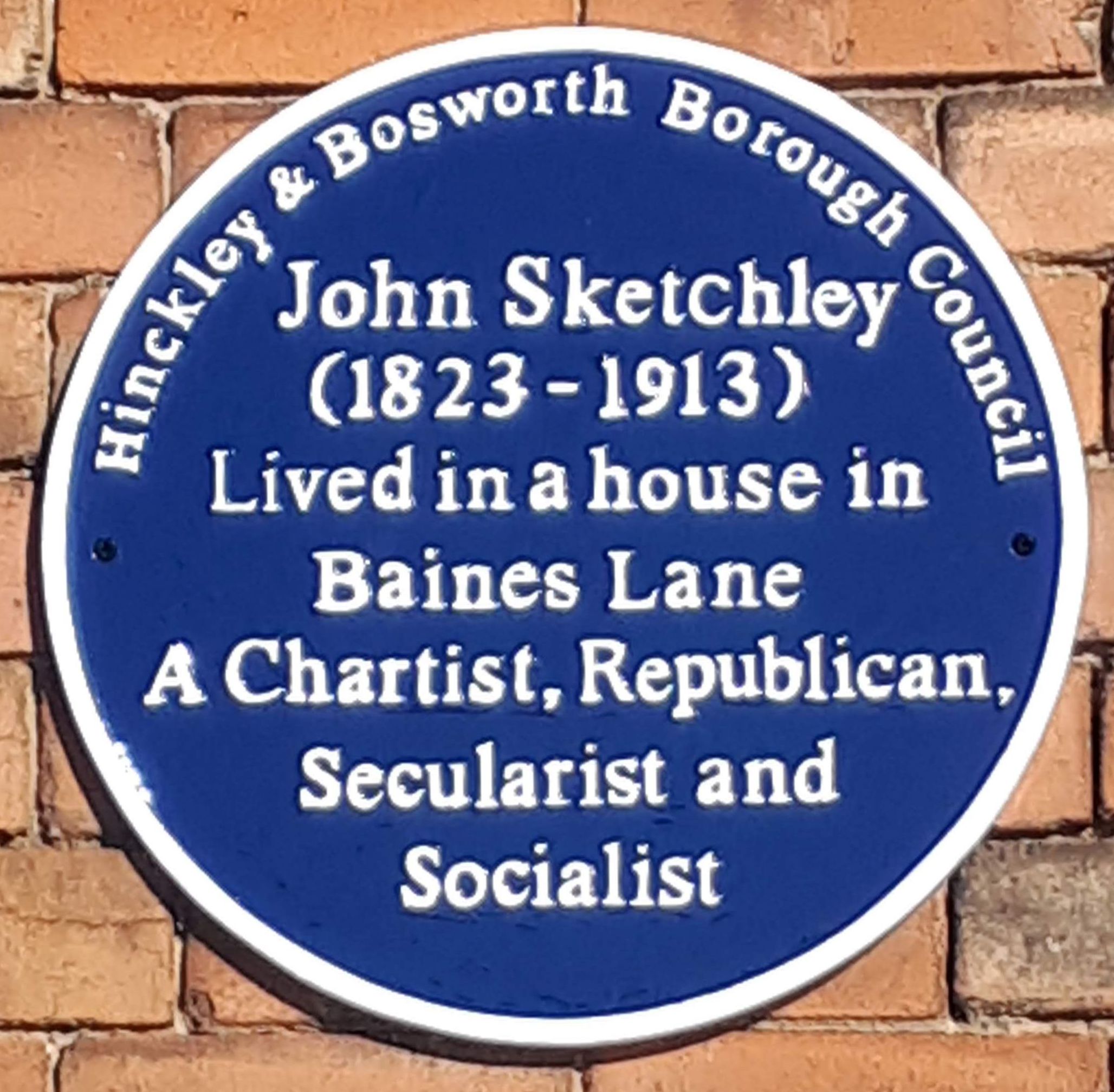

Born Hinckley: 1823, died: Billesdon workhouse 1913

(Chartist, Secularist, Republican, Socialist)

John Sketchley's father was a Hinckley stocking maker and John followed him into the trade. The family were Catholics and though his priest called on the congregation not to attend Chartist meetings, John ignored him and became an active Chartist. At the age of 17, he became secretary of the South Leicestershire Chartist Association and held the post for ten years. John did not accept the distinction between physical and moral force Chartism, still used by historians today. He wrote:

“The quarrels on moral or physical force were most lamentable; as though the use of physical force could never be moral; or as though moral and legal were synonymous terms. The fact being that the legal and moral are generally the very opposite of each other, while, as a rule, the quickest way to end a tyranny and oppression is the most moral and most legitimate.”

During 1848, when a Chartist insurrection was feared by the authorities, two unsuccessful attempts were made to arrest him. In 1847 he had become attached to the Socialist and Freethought movement started by Robert Owen and was a subscriber to George Julian Harney’s Red Republican which was on the left of the Chartist movement. (Sketchley’s first child born in 1851 to his second wife Lucy, was called Julian). He also helped to organise relief for the refugees of I848, studied the writings of Mazzini, and in 185I was associated with the republican engraver and journalist W. J. Linton. At this time he organised a republican group in the Hinckley area.

John remained a Catholic and said that he only left the church when : "I was thoroughly convinced that its claims were incompatible with human liberty and human dignity.” He was excommunicated by the Catholic Church in 1859 for writing a 26 page pamphlet entitled Popery: Its Supporters and Opponents which had been published by Holyoake in 1856. He claimed that this led to him being thrown out of his home.

During the 1850s, he actively opposed the system of frame rents and in 1855, he gave evidence to the Select Committee on the Stoppages of Wages. At that time he had been working as a framework knitter for 19 years and testified that ‘It is the general system in practice; every workman when he takes a frame knows that he shall have stopped from his earnings so much a week for rent’. He explained that in times of good trade there had been no objection to the 1s. frame rent, however, ‘As wages have got lower we have found that rents have remained the same as they were when wages were higher, and consequently they bear more heavily on the workmen now than they did at former periods….’

In 1859, Sketchley wrote a letter to The Midland Express on behalf of his fellow framework knitters in which he accused one employer of being a ‘truck-master.’ William Frederick Taunton, the owner of the paper was subsequently sued for defamation of character by the employer. In his evidence John Sketchley told the court:

I have been framework knitter till about the last 18 months.... The wide frame was introduced in our district 6 or 7 years ago. Taking the average, persons can earn at the narrow frame 5s. or 6s. a week. If man earned 8s. a week, the deductions far frame hire, seaming, candles, needles, would 2s. By working 15 or 16 hours I have earned at the narrow frame net wages 8s. or 9s.— (Cross-examined-) I am now an agent for an insurance, and have other matters. During the strike, I was the paid secretary. I attended the meetings of the committee, and was paid 3d. week (laughter).

The judge described Sketchley's letter as a "well written and temperate statement of facts," however in December 1859, Taunton lost the case and was left with expenses of £650. That same month, Sketchley's 37 year old wife Lucy died in agony from stomach cramps. Her death was described as suspicious and Sketchley came under scrutiny. It was even suggested that the cause of her death was from the poison he used to kill bed bugs. Sketchley gave evidence that Lucy frequently was jealous of him for being seen in the company of young women. However, the jury were unconvinced that there had been any foul play and whilst the cause of her death was not explained, Lucy did have a history of illness. One can only speculate as to whether the innuendoes in the press about Lucy's death had any connection with the libel action in which Sketchley was then involved.

Until the mid 1860s, Sketchley worked as an agent for the National Trades and Mutual Association in Hinckley, he was also a news-agent and tea dealer and seemed to have recurrent financial difficulties. One year after Lucy's death, he married 23 year old Mary Ann Osborne who was probably illiterate since she unable to sign the marriage certificate. In 1867, Sketchley moved to Leicester where he became a bookseller and stationer, living at 37 Willow Bridge St. In September 1867, he was elected Secretary of the re-established Leicester Secular Society. However in October of that year he went bankrupt and was imprisoned for debt. A subsequent article in the Labour Leader suggest that his financial difficulties arose from organising a series of lectures by the renown secularist Harriet Law. He wrote later: When, in 1867-8, I was engaged in the greatest struggle in which I was ever in, and which cost me about £200, as well as the loss of a good business..... The only help I received was from the Secular Society of Leicester, and from an old friend, Sir Henry Halford, of Whistow Hall. He was not released from prison until January 1869 and he then moved to Birmingham where he played an active part in the Birmingham Republican movement.

Although most of his subsequent activity took place outside Leicester, it is worth noting the influential role he had within the nascent Socialist movement. In 1872 and 1873 he was the chief contributor to the International Herald (afterwards the Republican Herald). The editor, W. H. Riley, writing of the value of Mr. Sketchley's articles in the issue of June 28th, 1873, said Sketchley has probably exceeded all other Englishmen in his explanations of true Republicanism. In 1878, he founded the Midland Social Democratic Federation, the first Socialist organisation of the late C19th. In 1879, he published a pamphlet called The Principles of Social Democracy, which E. P. Thompson credits with introducing continental socialist ideas to many future British socialists. In it he wrote:

The grand principle of social democracy is the brotherhood of the human race. All privileges arising from class distinctions, so called titles of honour and dignity, must be abolished. All that tends to create envy, hatred, or prejudice between peoples must be removed, and be replaced by whatever is best calculated to promote peace and concord.

His programme for a free Social State included:

adult suffrage, direct legislation by the people, the abolition of the standing army, of all state interference in matters of religion, the full freedom of speech, the press, of public meeting, of free association, the free administration of justice, of education, the nationalization of the land, mines, railways, etc., .... "that all industrial production, including agriculture, be based on the principle of association or co-operation to be organized by the state under the democratic control of the working classes,"

In 1883 he was one of the founders of a Birmingham branch of the newly-founded Democratic Federation. (This later became Hyndman’s Social Democratic Federation and he was still lecturing for it in 1901.) He returned to Leicester to lecture to the Secular Society on several occasions.

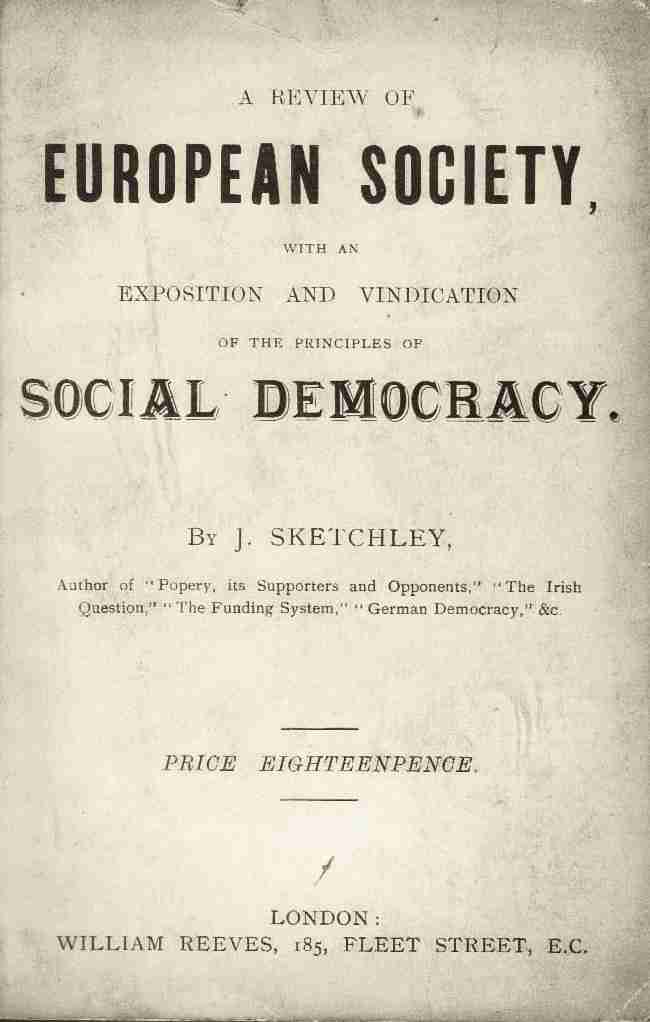

Sketchley became a prolific pamphleteer from 1880s onwards. In Land Common Property (1881), published by the Land Reform Union he gives a history of the arguments for the nationalisation of land, an analysis of the unequal ownership of land and concludes that there are enough resources for everybody. His other titles include: The Funding System, or how the People are plundered by the Bond-holding Classes, (1882) The Irish Question, (c1886), Shall The People Govern Themselves? (1890), The Workman's Question: Why He is Poor. (1890, Hull) The Crimes of Governments (1902).

Sketchley's articles for the socialist press drew on his long association with working class politics and touched on the issues which had been of concern in earlier years as well as in the 1880's, such as the Irish question. In 1884, he contributed a piece to To-Day which sketched his personal involvement in the latter stages of the Chartist movement and expressed his wish that contemporary radicals would learn from his experience.

In 1884, William Morris wrote a preface for his A Review of European Society and Sketchley was a contributor to Morris’ paper the Commonweal. In one article he criticised the Reform Bill of 1884 as being ineffective as it fell short of providing universal suffrage for both men and women. He argued that the Reform Bills of 1832 and 1867 had failed to change the character of the House of Commons and that the prospects for the new Bill were equally bleak.

In 1886, Commonweal published five articles by Sketchley on Church revenue and funding. For many years, radicals had wanted to break the links which bound Church and State in an unholy alliance. Sketchley argued that since the Church traced its tenure to Crown or state grants the public should rise up and take over the property that was rightfully theirs. He was outstanding among the old Chartists for his attention to international events and his patient compilation of facts and statistics. Writing in the Commonweal, he was scathing about the British Empire:

If we look at the Government of India, it is one of the purest despotisms ; and when Englishmen condemn the government of Russia in Poland, they ought to remember that the government of England in India is not in the least better.......Yes, wherever the British flag is carried, to whatever part of the world, there our only aim, our only object, is the enslavement of the people for the sake of plunder.

In the 1881 census Sketchley's occupation is given as a commission agent - being paid a percentage of the sales he was able to generate. However, he was was always dogged by financial problems. That year the 'Sketchley Recognition Fund' was set up by well wishers in Aston to benefit him. Frederick Engels made the disparaging comment that “Sketchley who, as a former Chartist, presumably considers himself entitled to a pension.”

By 1891, the 66 year old Sketchley had left his third wife Mary and moved to Hull with 25 year Emily. (She is listed as Emily Sketchley in the census) He frequently spoke about the radical past and when he spoke at Colne in 1900 on radical movements from 1817 to 1849 it was reported that: ‘taking into account Sketchley’s age, I think his pronunciation and voice wonderful.’

In 1900, the John Sketchley Testimonial Fund Committee published a pamphlet to raise money for him. The appeal noted that ‘during the last few years Mr. Sketchley has sustained several serious misfortunes and is anxious to re-establish himself’. In 1905, another appeal help noted that he was 'is in very reduced circumstances at the present time. He has vainly struggled to earn a livelihood in Birmingham as a reform newsagent and bookseller, but his great age and want of capital have precluded him from making a success of it.

In 1906 Sketchley moved back to Leicester, living at 46 Outram Street and from where he continued to sell his books and pamphlets. He wrote a series of articles for the Midlands Free Press in 1907 dealing with the 'land robbers' of the country. In 1908, he reprinted one article "Tithes and the Pious Ancestor Theory" which sold it for one penny.

Sketchley had 15 children, seven of whom had died by 1911. 90 year old Sketchley died in the Billesdon Workhouse in 1913, which was presumably close to where his younger brother Thomas was living. His death went unnoticed, even by the S.D.F.'s paper "Justice." In September 2019, a blue plaque was unveiled in Baines Lane in Hinckley where Sketchley had lived with Mary Ann in 1861.

Sources: Leicester Chronicle, 26th May 1855, Leicester Guardian, 19th November, 3rd December 1859, Leicestershire Mercury, 24th December 1859, Birmingham and Aston Chronicle 5th March 1881, Labour Leader, 15th September 1900, Reynolds’s Newspaper, 19th Aug. 1900, Clarion 24th June 1904, Commonweal 21 April 1888, Liberty 1st August 1895, Justice, 30th March 1901, Justice, July 19, 1884, 15 & 18, March 1905, 17 November 1906, 13 June 1908, David Nash, Secularism, Art and Freedom, Rhianydd Murray: Family, Work and Leisure in a Hosiery Town, Hinckley 1640-2000, J Sketchley Personal Experiences in the Chartist Movement, 1884, John Sketchley, "Political Reform and Social Revolution," Asa Briggs, Chartist Sudies, Christopher Draper, The Talented Mr Sketchley. Northern Voices, James Gordon Coolsen, The Evolution of Selected Major English Socialist Periodicals 1883-1889, Mphil thesis, Letter from F. Engels to Eduard Bernstein, 29th December 1884

|

.jpg) |

Born: Loughborough 1801, died 3rd January 1851 (Chartist)

John Skevington was the son of a leading Loughborough Primitive Methodist preacher and took up his father's vocation at an early age. He consequently became known as "the boy preacher" in his home town before embarking on a series of preaching tours around the country in the 1820s. His lameness compelled him to give up travelling and he continued preaching until he left the connexion in 1836. According to J.F.C. Harrison this followed a dispute about the financial problems facing Dead Lane Chapel, of which he was treasurer. By then, he was already well known in Loughborough as a democrat, and with the emergence of Chartism he was seen as a natural leader of the movement. He chaired the meeting in August 1838 of radicals set Loughborough Chartism in motion. By November, a local Chartist meeting could attract crowds estimated at being between three and seven thousand.

As an advocate of the principles of the People's Charter, I found nothing on inspection to condemn them.....but a firm conviction that though a man may be a Chartist and not a Christian, a man cannot be a Christian and not a Chartist unless through ignorance.

Through good times and bad, and through bitter division in the ranks of Leicestershire Chartism, Skevington remained a prominent and honourable figure at the head of the local movement. He chaired the meeting and demonstration which founded Chartism in Leicester and was a delegate to the 1839 Convention. He initially opposed but then voted for a National Holiday or Sacred Month (general strike) as a weapon to advance the Charter.

When general strike broke out in the summer of 1842, Skevington was arrested in Loughborough and whisked away to Leicester with an escort of Dragoon Guards. He was charged with using inflammatory language and bound over. Because he could not produce the necessary sureties, he was sent to county goal on High Cross Street in Leicester. Although he was released after a few days when satisfactory bonds were produced, his arrest roused the Loughborough Chartists to renewed action. This in turn lead to further arrests.

Skevington appears to have tried to reunite the different factions of Chartists in Leicester, chairing a meeting at which differences were aired. However, the splits continued until Cooper and Bairstow had departed from Leicester. In 1848, when the magistrates in Loughborough declared Chartist meetings illegal and prevented O’Connor from leaving the station, Skevington called their bluff and called a meeting in the Market Place. He also offered the services of the Chartists as special constables. In a letter to the magistrates he wrote:

I take the liberty, on behalf of the Chartist Body, and the Working Class in general, of tendering our services as Special Constables for the protection life and property, but not that of the rich only, but of our own, our wives, and our children. I am further induced make this offer, as are resolved not to have a second edition of 1842, when the heads of peaceable men were broken with the bludgeons of the Special Constables. We are for Peace, Law, and Order, but not on one side only. We are also resolved to have Liberty by peaceable and constitutional means, and thus make England really what it has been falsely represented to be - the wonder and admiration of the world.

Skevington remained a committed Chartist to the end and was held in high regard by his Loughborough comrades. In 1848 they presented him with a testimonial and his portrait in oils, ‘for his great services to the cause of liberty.’ This is now in the collection of Leicestershire County Council.

Sources: Leicestershire Mercury, 8th April 1848, Asa Briggs, Chartist Studies, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954, chartist ancestors

|

|

Born: Leeds, c1819 died July 12th 1883 (Secularist, Liberal)

John Sladen of Sladen's Indigo Dye Works, was a founder member of the Leicester Secular Society and had been active in Owenite circles in the 1840s and a supporter of Holyoake's Reasoner in the 1850s. He active in John Bigg's freehold Land Society was elected to the Board of Guardians in 1865 and continued until 1876. He attempted to stage operatic works at the Temperance Hall, but the committee and Thomas Cook were opposed. He was elected as an Independent Liberal Town Councillor for Middle St Margarets in 1876 with Daniel Merrick. He was a dyer of woollen yarn, employing 3 men in 1870. He was president of the Secular Society in 1873 and a shareholder in the Secular Hall Company. His particular hobby was music and could play most stringed instruments. He had a collection of old violin, cellos. etc. He played the cello and a prominent member of the Choral Society. He played in the orchestra at the Secular Hall and was probably in that of the Owenite Social Institution in 1840. He lived in Cobden Street and his only daughter married Councillor Collier. He died aged, 64 from cancer, soon after the Secular Hall was opened. His obituary refers to his kindness and geniality.

Sources: The Reasoner Vol 2 1847, Leicester Mercury 11th November 1854, Census Returns, Leicester Chronicle, 30th January 1869, 14th July 1883, Leicester Daily Post, 16th December 1920

|

|

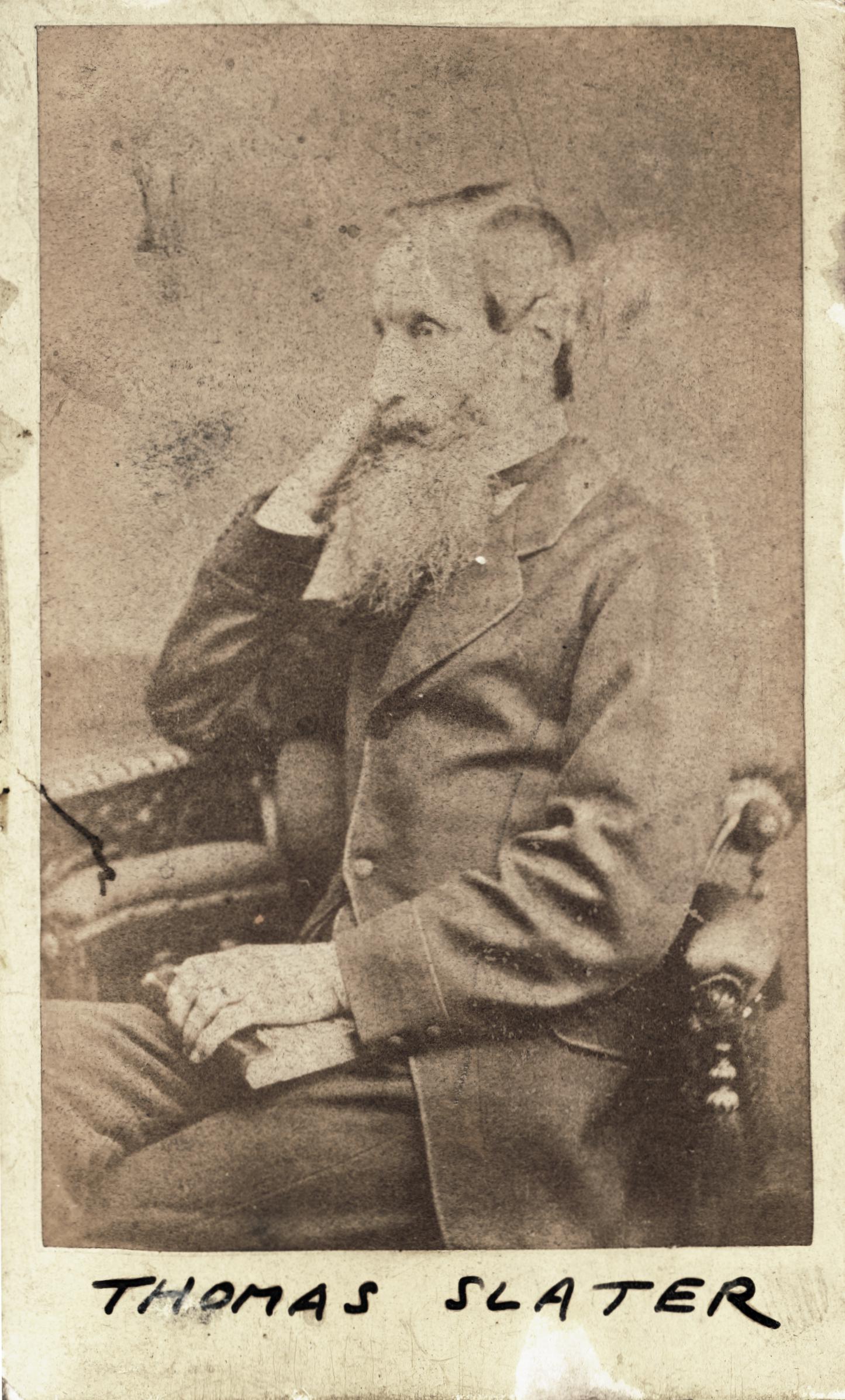

Born: Barnoldswick, Yorkshire 15th September 1820, died 25th June 1894

Tom Slater learned his trade as handloom weaver in Barnoldswick. In 1853 he moved to Bury. He became a close friend of Bradlaugh and intimate with G. J. Holyoake. In 1861, he was called on to give evidence at Bury Petty Sessions, but refused to take the oath on a Bible. He was told he could sent prison for seven days repeatedly until he took the oath. He was spared since the case went on without him.

For ten years he was a member of Bury Town Council and an energetic co-operator. He was a member of the first Central Board of Co-operators, which was appointed at the 1869 Congress. In the 1870s, he had appointed as one of the lecturers for the National Secular Society and in 1885 he accepted an invitation to become Manager of the Leicester Secular Society. When this arrangement finished he continued to reside on the premises with his son William who took over as manager. He continued to be an active co-operator in Leicester being elected to the L.C.S. general committee in 1887 and, as worker and lecturer, he won the respect of a wide circle of acquaintances. He had a passion for books and possessed a library of 3,000 volumes.

He had no friends amongst the police in Enderby when he and Tom Barclay were arrested and fined for obstruction whilst they were holding a public meeting. They were allegedly criticising the bible and denying the existence of a supreme being. Barclay described him as a strong Bradlaughite, Co-operator, and anti-Socialist, who advocated Malthusianism, Co-operation, and Land Nationalisation, and pooh-poohed Socialism.

Slater was a firm believer in the merits of cremation. When he died (at the Secular Hall) his body was taken by train to Manchester to be cremated, accompanied by his family and members of the Secular Society. This was so unusual, that it merited a long press report. Following his death, his photograph was hung in the Secular Hall lecture room along with those of Charles Bradlaugh, Michael Wright and Josiah Gimson.

Sources: Sources: Leicester Guardian, 10th August 1861, Leicester Chronicle, 17th Sep 1887, 7th July 1894, Commonweal, 4th August 1888, F. J. Gould, The History Of The Leicester Secular Society, 1900, David Nash, Secularism, Art and Freedom

|

|

Born: Burton-on-the-Wolds 1772, died: November 1847 aged 75 (Chartist leader)

Smart was born of working class parents, his father died whilst he was still young and his mother could not afford to keep him on at school. But he had learnt to read and had a thirst for knowledge. He managed to teach himself Latin, French, Italian and Spanish. He also had a talent for verse and contributed to several periodicals. These gifts and attainments brought him to the notice of the Marquis of Hastings who found him an appointment as a supervisor of excise. Early in life he had become a member of the Corresponding Society and after 17 years, he lost his job as a result of offending members of the Tory corporation in Leicester with his Radicalism. He thereafter eked out a precarious living partly from the lace-trade, as a school-master and also by making architectural drawings and machinery.

In August 1838, Smart was one of the speakers at the meeting to inaugurate Chartism in Loughborough. He was a delegate to the Chartist National Convention in 1839 where he opposed a proposal for a Sacred Holiday (general strike) to further the Charter. He was Skevington’s chief assistant at Loughborough until 1842, when he then moved to Leicester. Smart, unlike John Markham, was hostile to the repeal of the Corn Laws, believing that repeal would enable manufacturers to pay lower wages. Smart was a Shakespearian Chartist and idolised Fergus O'Connor. Following Cooper’s departure from Leicester, Smart, despite his age and poverty, attempted with George Buckby to revive the movement. In 1846 they formed the ‘O’Connor Chartist section,’ which the Northern Star described as a “few half-starved operatives aided by an old man nearly worn out in the service.”

Smart spoke at a crowded meeting at the Town Hall with Ernest Jones in November 1846 and by March 1847 he reported that 11,000 signatures had been collected in Leicester for the national Chartist petition, Smart's house on Sanvey Gate being one of the places to deposit the petition.

Smart contributed poetry to the Chartist Midland Counties’ Illuminator published in Leicester and to the Northern Star which published his last poem shortly before his death. In 1847, he wrote:

I have been active in the movement more than sixty years .... and ....from my early youth up, I have trod the bright path of democracy…I have received the usual reward of slander, of obloquy of persecution and pecuniary loss. My reward is that of an approving conscience and my consolation that when I depart, that I have endeavoured to leave the world a better place than I found it.

At his funeral, according to Skevington, the members and committee of three branches of the Chartist Land Company walked in front of the coffin, wearing black silk scarfs and hatbands and the road to the church was lined with spectators. Later, the Chartists held a meeting at the Amphitheatre where 1,500 people heard heard an oration on his life given by John Skevington and others.

Sources: Northern Star, 2nd January 25th July, 19th September, 27th November, 8th December1847, A. Temple Patterson, Radical Leicester, Leicester 1954, J.F.C. Harrison, Chartism in Leicester, published in Chartist Studies Asa Briggs (ed) 1959

|

|

Born: c1900; died: March 1938 (Communist Party)

Bill Smith worked at Partridge. Wilson and Co., Davenst Works on Evington Valley Road as an electrical fitter. He lodged on Mere Road with Bill Duncan. During the First World War he had served with the Yorkshire Regiment and was taken prisoner and interned in Germany. He came to Leicester from Bramley, near Leeds, where his parents lived. He was married.

He was an active trade unionist and Communist Party member and was Secretary of the Leicester Anti-Fascist Committee in 1934. Although he was a delegate from the Amalgamated Engineering Union, he was expelled from the Trades Council in 1937, along with Jimmy Bellfield for his Communist Party membership. This followed the Trades Council's acceptance, by a narrow majority, of the T.U.C. model rules which had barred Communists from membership of Trades Councils. As a result of his expulsion, Leicester No. 2 branch of the A.E.U. disaffiliated from the Trades Council in protest.

In 1937, he had became secretary of the short-lived Unity Campaign, between the C.P., I.L.P. Socialist League and other left organisations.

He was a member of the Leicester Spanish Aid Committee and helped to prepare Evington Hall for the Basque refugee children.

Bill Smith died of a heart attack whist in was attending a concert by the Leicester Symphony Orchestra at the De Montfort Hall. At the time of his death, he was wearing a medal awarded to him by Sir Walter Citrine for trade union activities in Leicester. On the Sunday before his death, he had taken part in a meeting in Leicester Market-place. His name was still inscribed on the Leicester Communist Party's banner in the 1970s.

Sources: Leicester Evening Mail 5th November 1934, 20th October 1937, 25th March 1938, Leicester Mercury 25th March 1938

|

|

Born: Stafford 1848; died: 1919 (Liberal)

Thomas Smith learnt his craft from his father and they went 'on the tramp' to Worcester and then to Stafford, where he became involved in the trade union movement. Tom Smith was originally secretary of the Staffordshire Riveters and became the first general secretary of NUBSO, from 1874-78.

He was elected to the School Board in 1877. In 1878, he resigned as secretary of the union in order to become the full-time secretary of the Leicester Liberal Association. As registration agent he would have represented the Liberals at the Registration Court. Some observers noted that elections could be won in these courts. Objections could be lodged to certain people being included or excluded from the register. At that time there many, apart from women, who were still excluded from the vote on the grounds of being lodgers through property qualifications.

Thomas Smith retired from that post in 1891 to become Leicester registrar of Birth, Marriages and Deaths. He then became a town councillor, alderman and then mayor in 1907-8. Following the Conciliation Act of 1896, he was appointed by the Board of Trade as Conciliator and Arbitrator in many trade disputes in all parts of the country.

He remained a member of No 1 branch until his death, He was awarded freedom of the borough and an O.B.E. in 1918 largely in recognition of his services as an arbitrator in industrial disputes.

Sources: Leicester Daily Post 6th November 1918, 6th December 1919, Bill Lancaster, Radicalism Co-operation and Socialism, Alan Fox, A History of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Workers, 1958

|

|

Joseph Henry Smith

Born: c1843, died: 6th November 1880 (Secularist)

From c1876, Joseph Henry Smith (not James see Nash) was employed as the manager of the Secular Club and Institute at 43 Humberstone Gate. It was reported that he was at one time a Sunday-school teacher in the Charles Street chapel and had worked previously as a warehousemen. He seems to have been used as a stock Secularist lecturer who filled the platform when no one else was available; though this was no reflection on his talents. In 1878 he occupied the platform on no less than 10 occasions and 14 during the following year. His lectures covered a wide range of subjects including the meaning of words to the life and works of the great thinkers including Socrates and Paine. He was able to talk on the fringe pseudo-scientific subjects such as Mesmerism and Vegetarianism which Secularists had inherited as part of their Owenite psychological and investigative legacy.

Smith also took part in disputations with the defenders of religion. One such debate with George Bishop lasted for two nights at the Corn Exchange in March 1876 and a report of the debate was duly published. Two months later he spent another two nights at the Temperance Hall debating "Is reason or Christianity, as found in the New Testament, the better guide for this life." The Secularists seemed to have abandoned this time honoured method of publicity in the 1880s when they came to realise that such debates often served to confirm people's existing views rather than change them. Smith was 37 years old when he died.

Sources: Leicester Daily Post, 25 March 1876, Leicester Daily Post, 27 March 1876 Leicester Chronicle, 13 May 1876, Gazetteer & Directory of Leicestershire & Rutland, 1877, Leicester Chronicle - Saturday 13 November 1880, David Nash, The Leicester Secular Society: Unbelief, Freethought and Freedom in a nineteenth century city. D. phil. thesis

|

|

Born: 26th July 1890; died: c1977 (I.L.P.& Labour Party)

William Smith received his early education at Medway School. He began work as a half-time errand boy at the age of 11. On leaving school, he joined the Post office working as a messenger boy, postman, postal clerk, telegraphist, and postal and telegraph Officer.

He was conscripted in 1916, but refused to be vaccinated by the army and at one stage refused to put on a uniform. His lack of co-operation resulted in him being kept on the front line with no respite, but fortunately he survived. He spent two and a half years in the Royal Garrison Artillery and was discharged badly gassed, having previously suffered from frostbite and trench feet.

He held various positions in the Labour Party and Postmen’s Federation. He became president of the Trades Council in 1926. He was elected to the Council for Abbey ward in 1925 and became Lord Mayor in 1946. In 1953, he became chair and leader of the City Council Labour group, when John Minto’s three year period of office ended. He retired from the chair of the Museums and Libraries Committee aged 70 in 1960. He is commemorated by William Smith House in Beaumont Leys. He was an advocate of temperance and a non-smoker.

Sources: Leicester City Council, Roll of Lord Mayors 1928-2000, election address 1923, personal knowledge

|

|

Born: July 1942, died: May 1996 (Labour Party)

Paul Sood was born in the Indian Punjab, the son of a Congress politician. Throughout his political life he insisted that the Punjab was an integral part of India, and fell out with some Sikhs as a result. But he was also one of the Indian High Commission's closest allies in British politics, and it was through his influence with the Commission that visa surgeries were established in Leicester.

After graduating as an engineer at Trent Polytechnic, he became an active trade unionist as a member of the ASTMS (the Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs), before leaving engineering to start his own business, first as an insurance broker and then as a travel agent.

Paul Sood was vice-president of the Hindu Council of Leicestershire, founding secretary of the Indian Passport Holders Association, a founder of the Leicester Asian Business Association and of the British Indian Councillors Association.