|

D-E

|

|

|

Born: Kettering circa 1836, died: 1885

In the late 1860’s, Edwin Dadley worked as a clicker in the shoe trade. He was critical of the Leicester Co-op for poor auditing and a ‘grovelling view of co-operation,’ which did not see beyond the provision of ‘bread and cheese.’ He believed that the Co-operative movement should desire the moral, mental and social elevation of the working classes. It should have “principles that recognise the interests of capital and labour as one – principles uniting capital, brains, hearts and heads, to lift men to their proper station, that teach employers to regard their employees as their brothers, as men with hopes, aspirations and like passions with themselves…” In 1873, Dadley was elected to the LCS board and was a member until 1877.

In 1872, Dadley was involved in setting up a local boot and shoe co-operative. It had 120 members and was about to set up in business when the proposal to establish up a C.W.S. boot shoe works in Leicester was made. This was welcomed by Dadley and his society and he then became John Butcher’s assistant at the C.W.S. works on Duns Lane. On Butcher’s resignation in 1878, Dadley was appointed manager. Whilst on business in Paris in 1885, he died suddenly and Butcher was re-appointed in his place.

In 1876, he was fined 10s for failing to have one his seven children vaccinated. In admitting the offence he said he would be doing wrong if allowed the child to be vaccinated. He was a deacon at Emanuel Church and was an active worker in the cause of temperance through various total abstinence societies. Dadley’s wife Anna (born circa 1838) was a member of the LCS education committee and president of the Co-op Women’s Guild during the 1890s.

Sources: Midlands Free Press, 27th November 1869, Leicester Co-operative Record, August 1885, Leicester Chronicle, 9 December 1876, 1 August 1885, Benjamin Jones, Co-operative Production, 1894, Leicester Co-operative Society, Co-operation in Leicester

|

|

(Labour Party)

Dorothy Davis was a former teacher and was a social studies lecturer when she was first elected to the City Council in 1970. She was the last chairman of the education committee before education was passed to the County Council. In 1972, she was one of nine Labour councillors who rebelled over issue of Ugandan refugees. They took issue with the ‘no room at the inn’ being approach taken by the leadership of the Labour group. She was subsequently elected as a County Councillor.

Sources: Valerie Marett, Immigrants Settling in the City, 1987, personal knowledge

|

|

Born: Ladywood, Birmingham, September 14th 1860, died: 1953

Frederic Lewis Donaldson received his early education at Christ Church Cathedral School, Oxford, where he was a member of the Cathedral Choir. He later entered Merton College, Oxford, to take Holy Orders. After having been ordained in 1884, he served in some of the poorer London curacies, where he began a long and detailed study of social questions to see how their solution could be united with the Christian faith. He married the daughter of Alderman Eagleston of Oxford in 1885, and after a year as rector of the colliery village of Nailstone in Leicestershire, became vicar of St. Mark’s Church, Leicester in 1896. Here, he initiated and supervised the painting of the sanctuary murals - seven large canvas panels painted in oils by J. Eadie Read of Gateshead on Tyne, depicting Christ as the Apotheosis of Labour. In a pamphlet describing the murals, Rev. Donaldson wrote:

“The Church of St. Mark’s stands in a town of 244,255 souls, of whom the greater number belong to what are termed ’the working classes’. St. Mark’s is one of the chief working class parishes of the town, and contains towards 15,000 souls. In this parish there is represented much of the tragedy and pathos, shame and horror of modern social conditions - infant mortality, child labour, underpayment or sweating of men and women, decadence of physical life, consumption and premature death....”

Rev. F. L. Donaldson was one of the founder members of the Church Socialist League, and between 1896 and 1906 was chairman of the Leicester Branch of the Christian Social Union. He was also editor of ’Goodwill’, a Journal of International Friendship, and led a deputation of Church of England clergy in 1913 to the then Prime Minister, Asquith, on the subject of women’s suffrage. But it as an organiser and leader of the Leicester Unemployed March that he is especially remembered.

Before the march, he wrote to Randall Davidson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, asking respectfully whether he would receive a deputation of unemployed marchers at Lambeth, but the request was refused. Donaldson replied in critical tones and the whole correspondence was published, causing much comment and arousing public opinion. Some believed that this later cost Donaldson the Bishopric of Birmingham.

During World War One, Canon Donaldson remained constant in his Christian pacifist position, and suffered a good deal of opprobrium from his wife as well as from his parishioners. In November 1914, he declared War betrays the innocent, crushes the weak, violates purity, destroys and devastates fair and noble cities and wrecks their habitations and he declared his conviction that, the real sin of the church is not that she allows war, but that she tolerates the state of things that leads to war.

In 1918, he was transferred from Leicester to the comparative quiet of the countryside of Peterborough as rector of Paston within Walton. In 1921 he was instituted Canon residentiary of Peterborough Cathedral.

In Ramsay MacDonald’s first episcopal appointment in 1924, he was made a canon of Westminster Abbey, where he acted as President of the London Council for the Prevention of War in 1927, and Chairman of the League of Clergy for Peace from 1931-40. Canon Donaldson steeped himself in the traditions and history of Westminster Abbey, and when approaching his nineties could be seen piloting round little groups of visitors who had no idea of his identity.

Sources: The Times, 8th October 1953 (obit), Barbara Butler, Vicar of the Unemployed, 2005, Malcolm Elliott: Opposition to the First World War: The Fate of Conscientious Objectors in Leicester

|

|

Born: Oxford, circa 1862, died 1950

Before coming to Leicester, Louise Donaldson was the first woman magistrate of the Soke of Peterborough. Louise Donaldson was active in the National Union of Women Workers (later known as the National Council of Women) She was also involved with the formation of the Leicester Health Society in 1906. She was a member of the Leicester & Leicestershire Women’s Suffrage Society and active in the Women's Labour League, becoming its president for 1914-15. Chairing its annual conference in 1917, she told the delegates that:

"we need urgently that the ban of subjection should be removed from womanhood itself as being a disastrous hindrance to the State, a clog artificial and absurd to our usefulness, and a serious injury to the status of wifehood and motherhood. It will seem to us that had women had their share in the management of affairs in our own and other countries, such a mess could not have come about."

Although she did not enjoy domestic work and had a servant, it was her view that a wife and mother should be paid directly by the state for her work to enable to her to give more time to her family.

Sources: Barbara Butler, Vicar of the Unemployed, 2005, census returns, Western Mail, 23rd January 1917, Common Cause, 26 January 1917

|

|

Born: 13th June 1898, died: 12 December 1971 (Labour Party)

Terence Donovan served in France in 1917-18 in the Bedfordshire regiment and later joined the RAF. After the war, he entered the legal profession and was called to the bar in 1924. He was selected as Labour's prospective candidate for Leicester East in 1938, but war halted elections. In March 1939, he wrote:

Anything less British than the National Government's treatment of those gallant defenders of democracy in Spain would be difficult to imagine, The recognition of General Franco has given pleasure to few people apart from those who contemplate with indifference, of with joy, the triumph of Fascist tyranny. There is deep misgiving even among the Government’s own supporters .... Even if we were not allowed actively to help the cause of democratic freedom in Spain, there was absolutely no reason why should hold Spain's hands behind her back while Mussolini and Hitler administered the knock-out from in front.

In 1945, he was elected as MP for Leicester East and was later sent on the British Government's legal mission to Greece in 1945. He continued to persue his legal career and in 1949, he became a director of the Daily Mirror Newspapers Ltd. Following boundary changes, he was elected for North East Leicester in February 1950. However, by July he had resigned in order to become a High Court judge. During 1960-63 he was Lord Justice of Appeal and during 1965-68 he served on the Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers Associations.

Sources: Leicester Mercury, 3rd March 1939, Who Was Who 1971-80, Vol VII

|

|

Born: c1903 (Communist Party)

Bill Duncan was communist activist during the 1930s and 1940s in Leicester. He had joined the Communist Party in 1922 in Scotland and become a full-time worker for the Young Communist League. He was sent by the Party to the International Lenin School in Moscow in 1929-30 The I.L.S. was established to train British Communists for leadership positions, establishing a core of within the Party who would always be loyal to the Soviet Union.

Bill Duncan was expelled from the school for embezzlement. According to Dorothy Adams he came to Leicester straight from Russia and was ‘full of it.’ (Russia) His daughter arrived with him knowing no English worth speaking of. He tried to get back into industry, but was thrown out of work every time he was discovered to be a Communist. He was barred from being a delegate to the Trades Council from the local AEU branch No 1, because of his membership of the C.P. He went to London in the 1940s, got a job in management and left the party.

Sources: Leicester Mercury 20th July 1938, Labour History Review April 2003, Forging the Faithful, D.M. Adams interview, Leicester Oral History Archive 1983

|

| E |

|

|

Born: 1852 Caythorpe, Notts, died: July 5th 1912 aged 60 (Secularist)

The Secularist shoemaker, Charles Eagle, was a dominant figure in the Anti Vaccination League. (along with Michael Wright and the Liberal MP P.A. Taylor) In May 1876, Charles Eagle and Frank Palmer were jailed for ten days for disobeying the law on vaccination. When they were released they went in a procession, dressed in their prison clothes, to the Market Place and received a homage of 15,000 cheering townsmen. On the many banners was an emblematical painting of an eagle soaring over the head of a doctor (described as " The disappointed doctor") with a child in its mouth. The doctor was represented as wielding a lancet, while the eagle appeared to be making its way towards a " stone jug," indicating the gaol.

In 1887, Charles Eagle was imprisoned again. By 1885, nearly 3,000 people were awaiting prosecution under the 1871 Vaccination Act and on 23 March 1885 some 100,000 protestors processed from the Temperance Hall to the Market Place where copies of the Vaccination Acts were burnt in full view of the Mayor and Chief Constable of Leicester. In 1887, Charles Eagle was imprisoned again for failing to pay a fine for not having his children vaccinated. The police did not seize his furniture, but 'took him from his bead and marched him two miles to prison.'

The 1885 demonstration had led to a royal commission that was appointed to investigate the anti-vaccination grievances as well as to hear evidence in favour of vaccination. The commission sat for seven years, hearing extensive testimony. Its report in 1896 concluded that vaccination protected against smallpox, but as a gesture to the anti-vaccinationists it recommended the abolition of cumulative penalties. A new Vaccination Act in 1898 removed cumulative penalties and introduced a conscience clause, allowing parents who did not believe vaccination was efficacious or safe to obtain a certificate of exemption. This act introduced the concept of the ‘conscientious objector’ into English law.

Charles Eagle was also a co-operator who had a long association with Equity shoes and was a member of the Trades Council. He was active in support of the Trades Council 'Labour' candidates for the Town Council in 1893. He died of T.B. and was cremated and then buried in Welford Road cemetery - the ceremony being conducted by the Secularist F.J. Gould who said that four words summed up Charles Eagle: "He was honesty itself."

Source: Leicester Chronicle, 20 May 1876, 17 June 1893, 13 July 1912

|

|

Born: Leicester, 1895, died: London 26th September 1981

The Secularist shoemaker, Charles Eagle's unvaccinated sons, Ronald (c1889-1947) and Edgar Eagle were also members of the Secular Society. Edgar was a Clerk at Equity Boot & Shoe works in Leicester. During World War One, the brothers were very active in of the Union of Democratic Control and became conscientious objectors. They were arrested under the Military Service Act for neglecting to report to the barracks at South Wigston in May 1916.

18 other men appeared in court with them on the same day. They had applied to the Appeal Tribunal for total exemption, but were refused and granted 'non-combatant status' and were liable to be called-up into the army, but not to be trained to use weapons. They believed that any alternative service still supported the war effort and in effect supported the immoral pursuit of war. All of the men were fined 40s and handed over to the military authorities.

Edgar had been ordered to join the Non Combatant Corps Northern 3 Unit in June 1916, where he was given 28 days Field Punishment no2 for disobeying orders. This involved being tied in chains and shackled to a heavy object, often a wheel. In a second court martial at Catterick in April 1917 he was given two years hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs. After three months, however, he was sent to a work centre set up in Dartmoor Prison.

Ronald Eagle spent 56 days in detention in Stafford Barracks for refusing to turn out on parade. After serving time at Wormwood Scrubs he was also transferred to Dartmoor.

In 1919, Edgar was a member of the Management Committee of Leicester Cooperative Society and was that year elected to the Leicester & District Executive Committee of the Workers Educational Association (WEA) having been an active member of classes in that Branch. In 1926, he went to Ruskin College and went on to study part-time at University College, Nottingham achieving a B.Sc. (Econ.) (Lond.) In 1929, he was appointed Staff Tutor in Economics in the Department of Adult Education, at University College, Nottingham and remained there until his retirement in retirement in 1960. He published a history of the East Midland WEA in 1954 and of the The Leicester Mechanics’ Institute in 1960.

Source: Leicester Daily Post, 25th May 1916, Annual Report of Leicester U.D.C., 1916, Malcolm Elliott: Opposition to the First World War: The Fate of Conscientious Objectors in Leicester, Denise Pakeman, New Ruskin Archives.

|

|

Born: Huncote, Leicestershire c1808, died Germantown, U.S.A., 28th December 1878 (Framework knitter)

Joseph Elliott was orphaned at the age of four and lived in Huncote with his uncle Joseph Freer until he was 21 when he married Martha Jeays. He had been ‘put to the stocking frame’ at the age of seven and moved to Leicester c1829. It is not known if he had any schooling, but he was very literate and wrote many petitions and flyers. well. The was also an able speaker.

Like many framework knitters he suffered dire hardship during the 1840s. He wrote that on more that one one occasion, when his family had no food, he took the furniture out of his house and sold it to buy bread rather than go to the parish for assistance. He said that typhus fever had visited his house three times and by 1852 he had buried three children and had six children still living, one of whom was disabled. He lived in Neale Street which was not far from Wharf Street and close to the home of his friend George Buckby. In 1847, he worked at Warner’s factory on Archdeacon Lane.

Joseph was a Chartist and supporter of Feargus O’Connor and around 1844 he named one of his sons Feargus. By 1848, he had become one of the leading lights in the Chartist movment and was on a county wide committee of three with Sketchley from Hinckley and Skevington from Loughborough to prepare for ‘contingencies.’

He was also active in the Framework Knitters Union and by the early 1850s, he was secretary of the Leicester Framework Knitters Committee. At this time both he and George Buckby campaigned against frame rents and the use of truck and stoppages from wages in the hosiery trade. Both men were a thorn in the side of the middle men, hosiers and of the Guardians and both were active in support of the more Radical Liberals.

The newly rebuilt workhouse had been opened in 1851 and the Guardians, now dominated by Liberals, had decided to administer the full force of the Poor Law. This involved the seperation of the sexes and families and the division of the workhouse inmates into various categories. In 1852, Elliott and Buckby wrote a paper detailing all the cases of abuse and injustices to inmates of the workhouse and they put it before the Guardians. These included the confinement of a man in the 'dark hole' for no good reason, that soup served was not fit for consumption, that the master had cruelly beaten seven boys, that he and the matron of the workhouse were drunk on several occasions, that a woman of 76 was kept on bread and water for two days and then locked up because she refused to work because she was ill. Allegations of the masters’ drunkenness were also made by the workhouse schoolmaster.

The Workhouse Master and his supporters proceeded to malign Elliott’s character. Elliot was accused of absconding from the workhouse in 1847-1848 and leaving his family to be supported by the parish. He was also accused of being drunk when he applied for relief. The Guardians made public the sums that they had allegedly spent on supporting the Elliott family. Joseph responded with a letter giving details of his life and circumstances.

Various respectable citizens (including John Markham, William Jones and Thomas Emery) wrote to say that the accusations were a fabrication and they provided testimony from several winesses to show that Joseph had not absconded and that much of the relief obtained was for the benefit of Elliott’s disabled son. They also criticised the guardians for the mixing of private circumstances into a public matter.

The Guardians discussed the allegations made by the schoolmaster, but as far as Joseph Elliott was concerned they 'knew what sort of a character he was… he had given them enough trouble already and he was was not a person of credit.’ They resolved to take no notice of Elliott & Buckby’s letter and then sacked the schoolmaster.

The same year Joseph Elliott successfully brought charges against a hosiery bagman (an agent of middleman) under the Truck Act where a stockinger was being paid by the bagman with meat, bread and candles. Presumably this was done on behalf of the Framework Knitters Committee. The organisation of the Leicester’s hosiery industry had many parallels with the 21st century gig economy. Framework Knitters were not directly employed and had to rent their knitting frames (their app) Middlemen or bagmen collected frame rents distributed the raw materials and collected the finished work and handled the money. Frame rents had to be paid whether there was work or not and were usually done so via stoppages from wages.

By April 1853, a petition signed by 12,000 in Leicestershire, 7,000 in Nottinghamshire, and 6,000 in Derbyshire,had been collected in support of Sir Henry Halford's bill to regulate frame-rents and charges. In 1853, Joseph Elliott was chairman of the Framework Knitters Committee and Bucky was the secretary and they led the agitation against the rents.

In March 1853, he had an interview with the Right Hon. E. Cardwell, at the Board of Trade, in London to give evidence of the heavy deductions made from knitters’ wages. The deputation consisted George Buckby, Joseph Elliott and Thomas Winters of the Glove Union.

In the winter of 1855-1956, there was widespread destitution in the town. At a public meeting Elliott spoke of the need to give the poor, not soup, but bread,coal and meat as well. In 1855, he and Buckby organised meetings in Leicester and Hinckley opposing the high price of bread. Elliott also acted as secretary to a woman's only meeting on the same issue. See Anne Wigfield

Both Elliott and Buckby were supporters of Joshua Walmsley's motion to allow the Sunday opening of museums and opponents of proposals to close pubs on Sundays. That, the opinion of this Meeting,

all places of rational instruction might be opened after Morning Service on Sundays without any impropriety or desecration of the Sabbath, …….it is the imperative duty of every lover of liberty of conscience to ensure …effective opposition to the perpetual meddling of the Sabbatarians who so recklessly attempt to deprive the working classes of their just rights…."

In 1856, they convened a meeting to condemn the Council for refusing to allow a band to play on Sunday afternoons on the racecourse. (Victoria Park)

By the mid 1850s, the Whig supporting Leicester Chronicle used the term Chartist to denigrate anyone who supported the estension of the franchise. As far as it regards the important question of the Suffrage, Sir J. Walmsley is a rampant Chartist. Were his views to be carried out, the legislation of this great country would be lodged in the band, of such men as Messrs. Buckby and Elliott, and the foundations of society would be overturned.

The Chronicle ran a story suggestuing that Elliott and Buckby were being paid 30/- a day and frequently referred to them as agitators. It is not suprising that they found it difficult to earn a living.

After the defeat of Henry Halford’s bill to regulate frame rents, he and Buckby were victimised by local employers and both emigrated to the U.S.A. They arrived in Philadelphia February, 1857 and settled in the hosiery town of Germantown where there were 800 framework knitters. In 1857, Elliott provided a vivid description of life, work and politics in the Philadelphia, which was at the time in the midst of a financial crisis.

I very much regret to see parties still arriving from the counties of Leicester and Nottingham…… I am told that many would return to England if they had the means to do so. When I look upon men and women who have been here five or six years, I feel surprised. Those who were stout, healthy, and robust when at home, appear to be almost used up; they seem to have aged 15 or 20 years. I never in tbe course of life saw people look so thin, sallow, and dried up; the broiling sun, the piercing frost, and the great and sudden changes of tbe weather, will soon take the mettle out of the stoughtest of John Bull's children, and leave them but mere skeletons of what they once were.

In 1860, his wife Martha died and Joseph remarried and ended up running a hardware store. Despite periods of unemployment, in 1871 Elliott and Buckby raised £24 which they sent back to Leicester for the proposed monument to John Biggs. The statue, in Welford Place, was unveiled on 15th April 1873.

Sources: Leicester Journal 30th April 1852, Leicestershire Mercury, 8, 15, 22 & 29 May, 3 July 1852, 28 April 1855, 8 December 1855, 23 February 1856, 5th July 1856, 14 November 1857, Leicester Journal 15 September 1871, Leicester Chronicle, 22 May 1852, 12 January 1856, 28 March 1857, 18 January 1879, Morning Post 17 March 1853, Justice 7th March 1903

|

Emery's 1849 essay was republished in 2010

The Leicestershire Movement, 1850

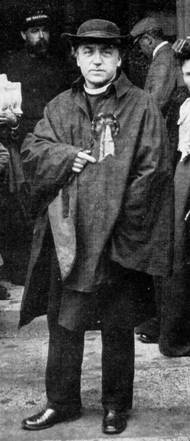

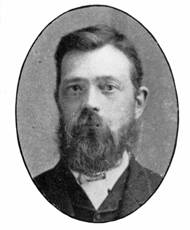

Thomas Emery at the laying of the Clock Tower foundation stone, 16th March 1868

|

Born Middleton Cheney, N’hants 4th February 1821, died: August 1868 (Owenite & Liberal)

Thomas' father William Emery was a maker of knotted stockings in Middleton Cheney, not far from Banbury. He sent Thomas to school and Thomas' talent as a writer was recognised by one 'old gentleman' who sent for him to write out various thymes he had composed. He was apprenticed as framework knitter and became a glove hand. This branch of the hosiery trade provided better wages than any other. He was studious and was known to sit at his frame with a book.

Although his obituary states that the Emery family came to Leicester in 1837, there is no evidence that they came with him. The 1841 census shows him lodging with a couple in Neale Street, close to Russell Square on Wharf Street.

He must have become an Owenite soon after Robert Owen's visit to Leicester in 1838, since the following year, Emery, aged 18, was writing to the New Moral World. By this time he was attending meetings, classes and discussions run by the local Leicester Branch of the Owenite Universal Community Society of Rational Religionists.

In 1843, he was secretary of the Owenite branch, now renamed the Rational Society. About the same time he became active in the Anti-Persecution Union which had been formed to defend those arrested for blasphemy. The APU, aimed to "assert and maintain the right of free discussion, and to protect and defend the victims of intolerance and bigotry." That year he married Elizabeth Pickard (1815-1850) the daughter of a framework knitter who lived on Wharf Street.

Although Emery seems to have had no position within the Chartist movement, he was a supporter of universal suffrage which included women rather than the universal suffrage for men only which was one of the Chartists' demands. In 1847, writing as T.E. in Holyoak's Reasoner, he reported that at meeting of Liberal candidates the question on extending the suffrage to women "was treated with evasive levity by the candidates and was met with by general laughter and derision from a crowded assembly of your Radical 'lords.'"

He was also scathing that in the metropolis of nonconformity, professed dissenters who wanted civil and religious liberties for themselves, were ready to deny those same rights to those of no-religion. He described the blasphemy laws as state interference with the consciences of others. In 1848, his membership of the Mechanics Institute was terminated after he wrote comments in favour of opening the Institute on a Sunday.

In 1849, three of his essays were published as pamplets. His first essay "The Causes of Crime: its Prevention and Punishment." won a two guinea prize offered by Samuel Stone, the Town Clerk, in an essay competition. The subject was "The Causes of Crime: its Prevention and Punishment." It was well received and had a favourable review in the Northern Star. In the pamphlet he argued that Ignorance is the Parent of Crime and to counter it a National Secular Education system was required. He hope that with education " an advanced state of civilisation will be attained; in which the rare victim of criminality will receive. other treatment than vindictive violence and sanguinary execution."

This was published as a pamphlet along with two other essays on education and wages. In his pamphlet on education, Educational Economy : or State Education Vindicated from the Votaries of Voluntaryism, he argues for State Education rather than the voluntary provision of schools. It was his view that the government should provide the best secular education for every individual, so that each shall have fair start in the world. In is review of the pamphlet, the Leicester Chronicle made the point that despite having none of the advantages of college or academy:

he writes and argues with an ease and force which many of his more privileged fellow-men may envy. The reviewer concludes by saying That men possessing such abilities should be found in the ranks of one of the worst remunerated departments of British industry, and that they should have to carry on a constant warfare with poverty, are among the wonders and anomalies of this age.

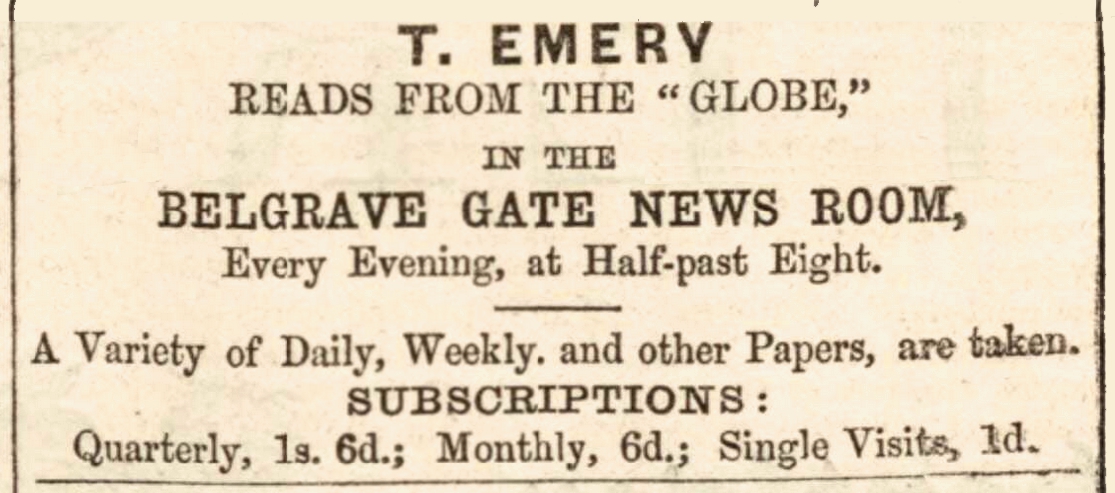

In 1850, Emery had set up in business, running a bookshop and newsroom at 148 Belgrave Gate, close to Leicester's worst slums. The business prospered and for a time he gave daily readings of the Globe newspaper in the evening, enabling those who could not read to keep up with the news. During this period Emery started two or three penny weeklies. One was named another The Movement (1850) of which ran for 19 editions and ran out of money. In 1853, his Leicester Fly Sheet made its appearance. No copies are known to have survive, but at least three editions are mentioned.

He wrote "A Comic History of Leicester" which was illustrated by an anonymous local artist and published in 1851. In 1850, he supported Thomas Cooper’s progress union and in 1851 he became the secretary of Society Of Theological Reasoners In Leicester. This was obviously borrowed from the title of Holyoak's paper the Reasoner and Theological Examiner. By 1853 the paper was re-titled The Reasoner and Secular Gazette and its supporters, a mix of freethinkers and former Owenite socialists were calling themselves the Leicester Secular Society. They met at Emery's News Room on Belgrave Gate for lectures and discussion. Along with the Unitarian missionary Joseph Dare, he was an agent for the People's Assurance Society.

In 1853, an attempt was made to revive the Chartist movement and the Leicester Charter Association met at Emery's Newsroom. He chaired a open air Chartist mass meeting, addressed by Ernest Jones, on 10th July 1853. That year was also a time when it was hoped that a parliamentary bill would end the iniquitous system of charging workers rent for knitting frames - even when there was no work. Emery produced a statement of reasons why Halford’s bill should be supported. Despite a 13,000 strong petition, one of Leicester’s two radical M.P.s, Richard Gardner, voted against the Bill. Emery then became active trying to keep working class support for Gardner in the hope that he would deliver on the questions of a New Reform Bill and on National Education. Unfortunately Gardner died in 1856.

Emery played a prominent part in the affairs of the St. Margaret's select vestry. This was the governing body of a parish, the members generally having a property qualification and being recruited more or less by co-option. It considerable powers which were eventually taken over by local authorities. In 1836, St Margaret's had levied a church rate and had taken proceedings against 21 dissenters who refused to pay. In 1837, the dissenters obtained control of the vestry and refused to authorize a church rate.

By the mid 1850s, the Secular Society had ceased its regular meetings at Emery's shop and was seeking to reconstitute itself. This may well have been the result his commitment to the Midlands Free Press which was a substantial enterprise and initially published in Kettering. Nevertheless, Emery was active in opposition to the Sabbatarians and in support of the radical Sir Joshua Walmsley's proposals for the Sunday opening of museums. In 1855, he opposed attempts to close pubs on Sunday because he saw Sunday closing as an infringement of individual liberty. In 1857, he acted as secretary to the public women's meetings called by Anne Wigfield and Mary Woodford to consider women’s property rights and was active in the meeting of 'non-electors' who were calling for the extension of the suffrage.

Emery played the violin and took part in the performance of such works as the Messiah or Creation as well as playing quadrilles and country dances. Along with John Sladen on cello, he must have been the band that playd in the Owenite Social Institution and he subsequently played in events organised by the Joseph Dare discussion group.

In 1858, Emery became the founding editor of the South Midlands Free Press and used the paper to support the Liberal cause. He was the local correspondent of the Morning Star and the Daily News and the first to introduce the London penny daily newspapers into Leicester.

From the late 1840s, the Liberals had been divided into two rival camps: the radicals and the so-called 'moderates.' From the mid 1850s, some of the evangelising clergy had switched their support from the Radicals to the Whigs or 'moderates.' In 1861, Emery was part of a delegation of ‘extreme Liberals’ who invited the radical P.A. Taylor to stand for Leicester. He did not win and the split Liberal vote gave the Tories a victory.

Emery gave his support to the Northern cause against slavery during the American civil war and was a member of the All Saints Open discussion group from 1849 until his death from heart disease.

In 1863, a testimonial was organised on his behalf and the press notice made the point that he was one of those who helped heal the split in the Liberal Party, ensuring the electoral success of an undivided party and the election of Taylor and after his election he remained in the M.P.’s confidence. Following Emery's death P.A. Taylor MP, made a contribution of £100 (£12,000 in 2019) to a fund established to help Mrs Emery and her family.

In 1863 he was one of the prime movers of bringing Garibaldi to Leicester. In 1867, he took a prominent role in another campaign over the price of bread, largely about 3½ lb loaves being sold as 4lb and was was among a deputation of Leicester Liberals who met with Gladstone.

His wife Elizabeth Pickard died in 1850, aged 33, probably whilst giving birth to her daughter Julia Emery, or soon after through complications. Shortly after Elizabeth's death, Thomas married Millicent Lewitt at the registrar's office. She came from a Unitarian clergyman’s family and this may explain this part of his obituary: “His history is of a self made man. By slow degrees he made his way out of the labyrinth of darkness and unbelief and attended services at the Great Meeting.” A year before his death, at a conference on why the working classes do not attend places of worship he said that the working man:

would see the expounders of his creed supported by an ecclesiastical establishment - the parsons taking sides with his oppressors. He imagines he can see it all. It is a cunningly-devised fable, to cheat him out of present advantages by exciting fallacious hopes for the future. Infallibility fails him, his faith gives way, and be has no disposition to attend at public worship.

Emery was at the heart of Leicester radical politics for many years and was active in garnering working class support for the radical wing of the Liberal Party. His second wife Millicent (born c1815) continued as an active supporter of the radical cause well into the 1870s. The are both buried in plot 347 in the unconsecrated part of Welford Road Cemetery.

Sources: New Moral World, November 9th 1839, The Reasoner, Vol 3, 1847, vol 10, June 1851,vol 20, 9th March 1853, 1856, vol 25 1860, Northern Star, 13th October 1849, Leicestershire Mercury, 8th January 1848, 21 April 1849, 6 July, 9 November 1850, 14th May 1853, 18th April, 3rd October 1863, Leicester Journal, 30 November 1849, 8th April 1864, People's Paper, 16th & 23rd July 1853, The Midlands Free Press, 22nd August 1868 (obit), The Causes of Crime: Its Prevention and Punishment, Thomas Emery, J. Ayer, High-street, Leicester, 1849, also included in Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises, 1800-1926, Gale Ecco, 2010, Comic History of Leicester, Arthur Hall & Co. 1851, Leicester Chronicle, 31st March 1849, 24th February 1855, 9th March 1867, 22nd August 1868, VCH, The City of Leicester (1958)

|

|

Back to Top |

|

© Ned Newitt Last revised: September 13, 2024.

|

|

|

Bl-Bz

Leicester's

Radical History

These are pages of articles on different topics.

Contact

|